Article Database

Teen Spirit

America's freakiest rock band found themselves threatened by rednecks and greasers. Then, run out of both Phoenix and LA, they chanced upon a riff and an idea that transformed them into global superstars. Alice Cooper re-lives making the epochal School's Out, while Stevie Chick dodges the blades and low-flying bar stools...

DECEMBER 1972. At the studios of BBC Television Centre in White City; west London, the Top Of The Pops Christmas Special is underway. The show's scattershot bill this evening reflects a decade that, culturally, hasn't quite found its groove yet, in much the same way as the '60s didn't really get started until the inaugural peal of harmonica that opened The Beatles' Please Please Me back in March '63.

Gary Glitter, Slade and Marc Bolan's T.Rex have all made appearances on tonight's show, proof that glam rock is in the ascendancy. But the lion's share of music is the kind of novelty tat that might prove baffling to a modern audience: Benny Hill's chart-topper Ernie (The Fastest Milkman In The West); Pan's People evoking the inconsolable longing of Nilsson's Without You by dressing like garlic bulbs and spinning around; and the bewildering sub-oompah boogie honk of Lieutenant Pigeon's Mouldy Old Dough.

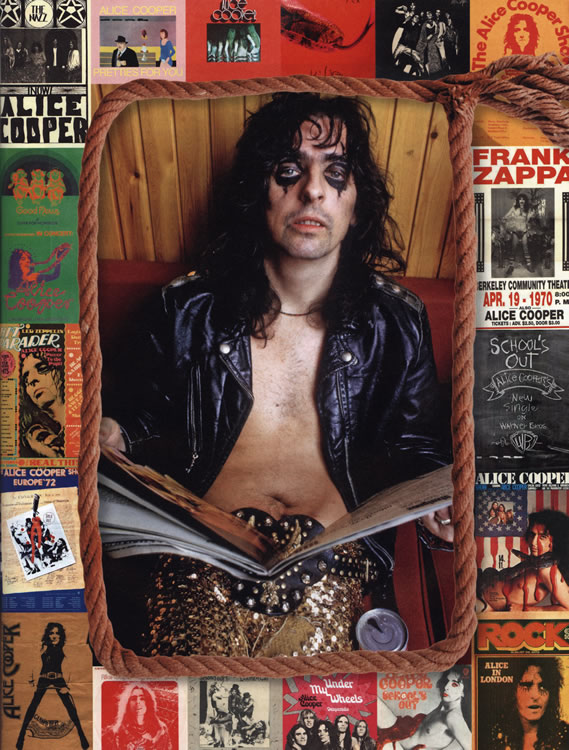

As the saccharine strains of toothsome pre-teen heartthrob Donny Osmond's Puppy Love fade away, however, the camera cuts to four surly, long-haired Americans, gussied up in stack-heeled boots and shiny silk playsuits drizzled liberally with sequins. They are led by what appears to be a wizened crone in ripped black leather pants, black strangler's gloves, a black piratical blouse cut open to his navel, lank black hair and black make-up staining his eyes and cheeks so he resembles a cross between Bette Davis in Whatever Happened To Baby Jane? and a particularly gnarly Manson Family member.

Over a staccato riff he'll later accurately describe as "bratty", 24-year-old Vincent Furnier — now better known as rock star Alice Cooper, also the name of his band — proceeds to wield a red balloon with unlikely menace, thrust a fencer's rapier down the lens of a BBC TV camera and, following a particularly fiery twin-guitar freakout courtesy of sidemen Glen Buxton and Michael Bruce, grab an angelic pubescent audience member by her hair and pretend to hang her, all the while singing of a student uprising that makes the climax of Lindsay Anderson's 1968 movie If... look tame.

"School's ... Out... For ... Ever!" Alice snarls, accompanied by an off-screen children's choir. Then, as he drags the blade of his sword across his neck: "School's ... Been blown ... To pieces!"

All across the UK, viewers' grumpy dads are choking on their turkey leftovers, while Mary Whitehouse and her moral majority race to their desks to pen letters of complaint. But nothing can stop these lurid collegiate arsonists, with their props, their make-up and their bad-ass tunes. Earlier that year, School's Out topped the UK charts, with the School's Out album reaching Number 2 in the US. Unlikely as it seems, Alice Cooper is about to become one of the world's greatest rock 'n' roll stars, and then nobody will be safe.

Least of all Vincent Fumier himself.

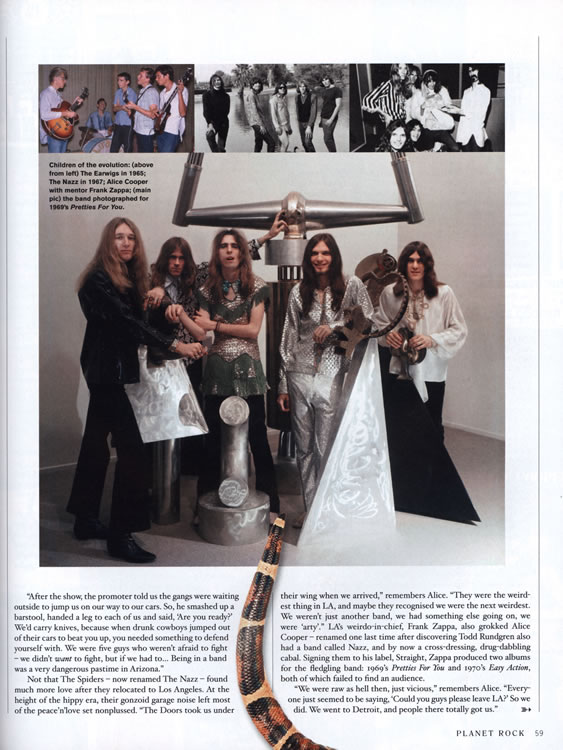

ALICE COOPER'S 'overnight success' was a good eight years in the making. The group started life as The Earwigs, a Beatles-influenced garage ensemble the 16-year-old Furnier formed in 1964 with fellow pupils — including Glen Buxton (guitar) and Dennis Dunaway (bass) — to compete in the annual talent show at their high school in Phoenix, Arizona. Soon, in a transformation that would frankly baffle most entomologists, The Earwigs became The Spiders and began playing local bars, with future Alice Cooper drummer Neal Smith and rhythm guitarist Michael Bruce later joining the line-up. None of the quintet was a native Phoenician — Furnier was born in Detroit, while his bandmates originated from Ohio, Oregon and Kansas. There were other reasons why they found themselves outsiders in Phoenix, too.

"In Arizona, you couldn't go out if you had long hair," says Alice today. "And we had hair that just touched our collars. I had two friends who got beaten to death by cowboys. The local cowboys were like the worst gang you ever saw."

The cowboys weren't the only predators in town, however — the group also had to face off hordes of leather jacket-clad greasers and Mexican gangs. "One time we played Tucson, and the Mexicans were on one side of the room and the greasers on the other side, and were fighting each other over who got to kill us," laughs Alice. "Glen was a total greaser — wearing a vest, cigarette in his mouth, playing his guitar. A greaser girl came up and asked him to play Louie Louie, and he tapped cigarette ash into her cleavage. And the greasers were all, like, 'This guy's OK — that's the kind of thing we'd do!'

"After the show, the promoter told us the gangs were waiting outside to jump us on our way to our cars. So, he smashed up a barstool, handed a leg to each of us and said, 'Are you ready?' We'd carry knives, because when drunk cowboys jumped out of their cars to beat you up, you needed something to defend yourself with. We were five guys who weren't afraid to fight — we didn't want to fight, but if we had to... Being in a band was a very dangerous pastime in Arizona."

Not that The Spiders — now renamed The Nazz — found much more love after they relocated to Los Angeles. At the height of the hippy era, their gonzoid garage noise left most of the peace 'n' love set nonplussed. "The Doors took us under their wing when we arrived," remembers Alice. "They were the weirdest thing in LA, and maybe they recognised we were the next weirdest. We weren't just another band, we had something else going on, we were 'arty'." LA's weirdo-in-chief, Frank Zappa, also grokked Alice Cooper — renamed one last time after discovering Todd Rundgren also had a band called Nazz, and by now a cross-dressing, drug-dabbling cabal. Signing them to his label, Straight, Zappa produced two albums for the fledgling band: 1969's Pretties For You and 1970's Easy Action, both of which failed to find an audience.

"We were raw as hell then, just vicious," remembers Alice. "Everyone just seemed to be saying, 'Could you guys please leave LA?' So we did. We went to Detroit, and people there totally got us."

It wasn't just the change in scenery that changed things for the band. Arriving in Detroit they found a local scene dominated by kindred spirits, most notably The Stooges and the MC5. They also found a man who would help them translate their sound from the stage to the studio — Bob Ezrin, then working for Jack Richardson, the Canadian producer who had made stars of Winnipeg rockers The Guess Who.

"Our manager, Shep Gordon, wanted Jack to produce us," says Alice. "Jack wanted nothing to do with us, so he sent Bob to see us at Max's Kansas City, to get rid of us. But Bob loved us. He saw a future in us."

Ezrin pared back the group's wildness and ill conceived virtuoso ambitions. "We wanted to be The Yardbirds," says Alice, "but Bob said, 'No, dumb it down."' Sculpting the group's first Top 40 single, Eighteen, from a chaotic studio jam, Ezrin produced two albums for the group in 1971 — Love It To Death (which peaked at Number 35 in the US albums chart) and Killer (Number 21). While Ezrin clearly got the band to channel their raw energy, adding structure to their music, his production nous also allowed them to retain their outré sense of self. It was this combination of a new sound as well as their original flamboyance and horror-inspired shtick that allowed the band to attract a new audience, most of whom were weirdos.

The mainstream, however, still eluded Alice's eldritch grasp.

"We didn't really appeal to the 'normal' kids, the Crosby, Stills & Nash fans," Alice admits. "We appealed to the outsiders. And it turned out there were a lot of outsiders. They chose us. I was their leader, and they were our gang."

Soon, that gang would swell with hundreds of thousands of new pledgers, as Alice and his band chanced upon a message every kid could identify with.

SCHOOL'S OUT began with a moment of inspiration, an intra-band chat during a break in jamming and — as with all wonderful rock songs — with a riff.

"To us, rock'n'roll was about tapping into what we were like as kids," says Alice. "What does every kid hate more than everything else? School! And what was the greatest moment of the year? The last three minutes of the last day of school! You couldn't wait for that bell to hit three o'clock, because then you would be free. I said, We've got to capture that last three minutes of the last day of school on tape — that joy.

"Glen Buxton was the biggest Bowery Boy of all time," continues Alice, referencing the juvenile New York street toughs who starred in movies in the '40s and '50s. "He couldn't wait to get away with something. He was the American Keith Richards — there was always two illegal things in his pockets at any one time, either a switchblade, or a joint, or a pill... a true juvenile delinquent. He came up with this guitar line — 'Dun dun DER, dun dun DER, dun dun der DER DERRR' — this bratty thing. That was just him, sticking it to The Man.

"The riff inspired the whole brattiness of the song. The lyrics, meanwhile, were written in the voice of a Bowery Boy, all mean and wiseguy-esque. And when that chorus arrived, I knew this was an anthem. Every kid in the world is going to be singing this. That might've been the only song I ever wrote where I was pretty sure it was going to be a hit. With all the touches Bob put to it, and the attitude of the song, I felt like, If that's not a hit, I don't belong in this business."

Most inspired among the touches Ezrin added to the production was the presence of a choir of snotty school kids singing the backing vocals, a trick Ezrin would repeat while recording The Wall with Pink Floyd seven years later. "Ezrin said, 'We gotta have kids — real kids — on the track, singing, No more pencils, no more school books...' And you hear 'em laughin' and screamin', like it's the last day of school. The song was hard-ass, it wasn't wimpy. But it really is joyful. We actually captured that feeling of the last three minutes of school."

For the rest of the album, the band expanded upon their Bowery-Boys-blow-up-the-school concept and tapped into another key early influence that the band shared — 1961's big-screen adaptation of West Side Story. Proof, indeed, that Alice Cooper were a pretty cultured bunch of guys, on the quiet.

"When we started playing as The Earwigs, we did the same thing all young bands do — play other people's music for four hours a night," says Alice. "The Beatles, The Yardbirds, The Kinks, The Who." But Alice Cooper's inspirations went beyond the cream of the British invasion. "When we started writing our own stuff, we took everything we knew and threw in some other stuff: a little Stockhausen, a little John Barry, and a whole lot of West Side Story. In our early shows we'd play out Sharks vs Jets gang fights, with real switchblades, and the real blood on-stage used to bum all the hippies out. We were more than a little Broadway.

"So, we all loved West Side Story. We identified with the gangs, we all wanted to be in the Sharks or the Jets. And the music was so up, so in-your-face. We wanted to tap into that, give every song this really sneering 'punk' attitude about life. So, you've got [second track on School's Out] Luney Tune, and it's all, 'Slipped into my jeans, feeling hard, lookin' mean...'"

Meanwhile, Gutter Cat Vs The Jets made the West Side Story connection even more explicit, its carnal feline metaphors giving way to a gleeful vamp on the Stephen Sondheim/Leonard Bernstein Jets battle hymn. Cooper chews the scenery throughout, his performance campy as hell, but the band leave you in no uncertainty that every one of them knows how to wield a musical switchblade, bassist Dennis Dunaway in particular.

"Man, that bassline was great," marvels the Coop, lost in the memory of cutting the track at New York's Record Plant. "Dennis was a lead bassist, he didn't play like anyone else. He loved Paul Samwell-Smith of The Yardbirds, and that was his launching point, but he went from there and created his own world. Pretty soon, we were all following him. Ezrin said, 'Dennis has written this great bassline and I pretty much think the whole song needs to be built around that.' So that's what we did."

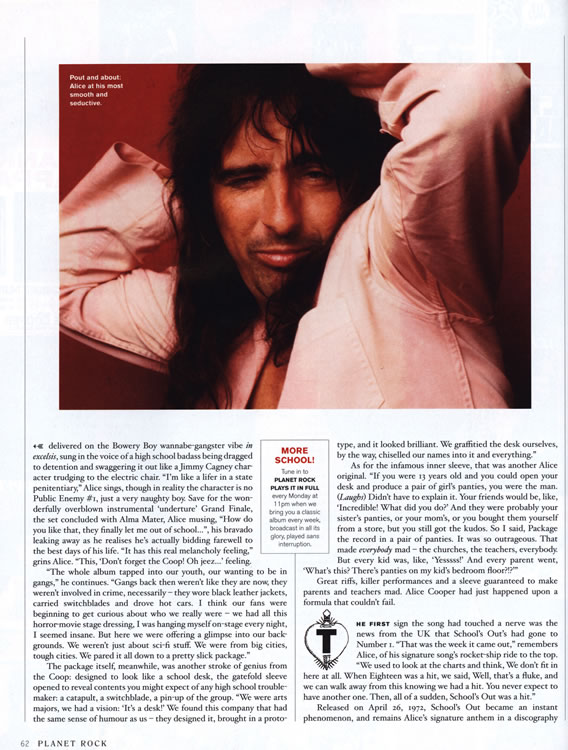

Public Animal #9, meanwhile, delivered on the Bowery Boy wannabe-gangster vibe in excelsis, sung in the voice of a high school badass being dragged to detention and swaggering it out like a Jimmy Cagney character trudging to the electric chair. "I'm like a lifer in a state penitentiary," Alice sings, though in reality the character is no Public Enemy #1, just a very naughty boy. Save for the wonderfully overblown instrumental 'underture' Grand Finale, the set concluded with Alma Mater, Alice musing, "How do you like that, they finally let me out of school...", his bravado leaking away as he realises he's actually bidding farewell to the best days of his life. "It has this real melancholy feeling," grins Alice. "This, 'Don't forget the Coop! Oh jeez ... ' feeling.

"The whole album tapped into our youth, our wanting to be in gangs," he continues. "Gangs back then weren't like they are now, they weren't involved in crime, necessarily — they wore black leather jackets, carried switchblades and drove hot cars. I think our fans were beginning to get curious about who we really were — we had all this horror-movie stage dressing, I was hanging myself on-stage every night, I seemed insane. But here we were offering a glimpse into our backgrounds. We weren't just about sci-fi stuff. We were from big cities, tough cities. We pared it all down to a pretty slick package."

The package itself, meanwhile, was another stroke of genius from the Coop: designed to look like a school desk, the gatefold sleeve opened to reveal contents you might expect of any high school troublemaker: a catapult, a switchblade, a pin-up of the group. "We were arts majors, we had a vision: 'It's a desk!' We found this company that had the same sense of humour as us — they designed it, brought in a prototype, and it looked brilliant. We graffitied the desk ourselves, by the way, chiselled our names into it and everything."

As for the infamous inner sleeve, that was another Alice original. "If you were 13 years old and you could open your desk and produce a pair of girl's panties, you were the man. (Laughs) Didn't have to explain it. Your friends would be, like, 'Incredible! What did you do?' And they were probably your sister's panties, or your mom's, or you bought them yourself from a store, but you still got the kudos. So I said, Package the record in a pair of panties. It was so outrageous. That made everybody mad — the churches, the teachers, everybody.

But every kid was, like, 'Yesssss!' And every parent went, 'What's this? There's panties on my kid's bedroom floor?!?"'

Great riffs, killer performances and a sleeve guaranteed to make parents and teachers mad. Alice Cooper had just happened upon a formula that couldn't fail.

THE FIRST sign the song had touched a nerve was the news from the UK that School's Out's had gone to Number 1. "That was the week it came out," remembers Alice, of his signature song's rocket-ship ride to the top. "We used to look at the charts and think, We don't fit in here at all. When Eighteen was a hit, we said, Well, that's a fluke, and we can walk away from this knowing we had a hit. You never expect to have another one. Then, all of a sudden, School's Out was a hit."

Released on April 26, 1972, School's Out became an instant phenomenon, and remains Alice's signature anthem in a discography packed to the gills with rock'n'roll brilliance. Its sales — along with that of its parent album, which went Top 10 across the globe — sent the group into a new strata of fame and success. "And we didn't know how to handle it," says Alice. "There's no pamphlet that tells you how you handle it, you just have to work it out."

The material changes were immediate. "We were staying in our own rooms at hotels now, rather than sharing motel rooms, and flying on airplanes, instead of driving to gigs. And honestly, we didn't know what to do with the money. We didn't have time to spend it, because we were always on tour, and if we weren't on tour, we were making a record. We had no social life at all, nobody was married, everybody was just living on the road. I didn't even have an address. That went on for seven, eight years."

As a certain pair of fictional Alice Cooper fans would later describe it, life for Alice and his bandmates during this era was very much "Party Time! Excellent!".

"Now, suddenly we were connected to this upper echelon of rock'n'roll groups," he says. "We'd get to the hotel and see the Faces there, and go, Fraternity Party! Because you were all in a fraternity together — anybody who was in a band was a brother, because you'd all played in the same gigs, you'd all stayed at the same hotels, slept with the same girls... "

This newfound sense of kinship with his heroes soon saw Cooper inaugurate his own celebrity drinking club, the Hollywood Vampires, clinking glasses with rock's A-List. "I could sit with a John Lennon, a Harry Nilsson, a Keith Moon, and I had a lot in common with everybody. I mean, John was a Beatie, so he was royalty, but he never acted like royalty, he was just one of the guys who was also a Beatle."

This rollercoaster of success sent Furnier along a path that ended in rehab in the early '8os after he almost died of liver cirrhosis. Now a born-again Christian who still tours as often as he can, Furnier has struck a much healthier balance between his real life and that of his alter ego. The recent release of his 26th studio album, Paranormal, proves he still has a lot of music left in him. But for all the personal torment that followed School's Out, he regrets nothing.

"You never know if or when you're going to get 'that song'," he adds. "It doesn't matter how many great songs they wrote after My Generation, when I think of The Who, I think about that song. Satisfaction was the song that made the Stones, that was their signature. School's Out will always be the signature song for Alice Cooper. And every May, it becomes the most-played song in the country, because every school plays it over the loudspeaker.

"It doesn't matter if we're playing Peru or Japan, the song is the anthem for every school kid in the audience," Cooper concludes, "and every person who remembers what those last three minutes of the school year felt like."

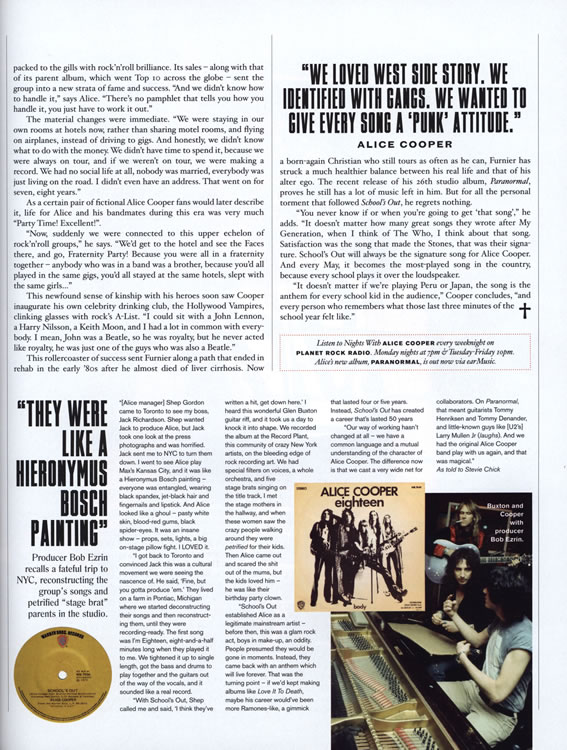

"They were Like a Hieronymus Bosch Painting"

Producer Bob Ezrin recalls a fateful trip to NYC, reconstructing the group's songs and petrified "stage brat" parents in the studio.

"[Alice manager] Shep Gordon came to Toronto to see my boss, Jack Richardson. Shep wanted Jack to produce Alice, but Jack took one look at the press photographs and was horrified. Jack sent me to NYC to turn them down. I went to see Alice play Max's Kansas City, and it was like a Hieronymus Bosch painting — everyone was entangled, wearing black spandex, jet-black hair and fingernails and lipstick. And Alice looked like a ghoul — pasty white skin, blood-red gums, black spider-eyes. It was an insane show — props, sets, lights, a big on-stage pillow fight. I LOVED it.

"I got back to Toronto and convinced Jack this was a cultural movement we were seeing the nascence of. He said, 'Fine, but you gotta produce 'em.' They lived on a farm in Pontiac, Michigan where we started deconstructing their songs and then reconstructing them, until they were recording-ready. The first song was I'm Eighteen, eight-and-a-half minutes long when they played it to me. We tightened it up to single length, got the bass and drums to play together and the guitars out of the way of the vocals, and it sounded like a real record.

"With School's Out, Shep called me and said, 'I think they've written a hit, get down here.' I heard this wonderful Glen Buxton guitar riff, and it took us a day to knock it into shape. We recorded the album at the Record Plant, this community of crazy New York artists, on the bleeding edge of rock recording art. We had special filters on voices, a whole orchestra, and five stage brats singing on the title track. I met the stage mothers in the hallway, and when these women saw the crazy people walking around they were petrified for their kids. Then Alice came out and scared the shit out of the mums, but the kids loved him — he was like their birthday party clown.

"School's Out established Alice as a legitimate mainstream artist — before then, this was a glam rock act, boys in make-up, an oddity. People presumed they would be gone in moments. Instead, they came back with an anthem which will live forever. That was the turning point — if we'd kept making albums like Love It To Death, maybe his career would've been more Ramones-like, a gimmick that lasted four or five years. Instead, School's Out has created a career that's lasted 50 years.

"Our way of working hasn't changed at all — we have a common language and a mutual understanding of the character of Alice Cooper. The difference now is that we cast a very wide net for collaborators. On Paranormal, that meant guitarists Tommy Henriksen and Tommy Denander, and little-known guys like [U2's] Larry Mullen Jr (laughs). And we had the original Alice Cooper band play with us again, and that was magical."

As told to Stevie Chick