Article Database

The Selling of Alice Cooper, 1965-1975

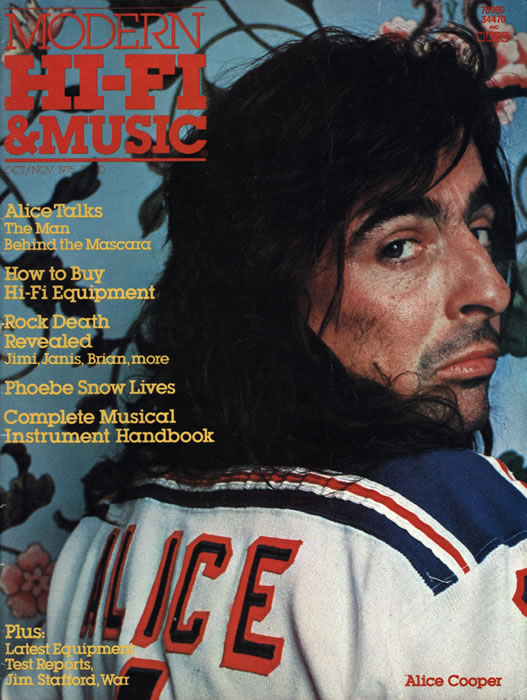

The Selling of Alice Cooper, 1965-1975 Toby GoldsteinAlice Cooper is on tour. He's making an exhaustive series of appearances at America's major halls, well over two months in duration, shows that will sell out. Shows that will always attract attention, though Alice has long renounced the baby-killer image in favor of America's new found son, golfing pal to the famous, the man who might get Bob Hope to call rock'n'roll at least one good name. Alice Cooper has cut his hair.

Making an appointment to see Alice on the road is slightly less difficult than booking time with the Pope. Appointments are precision timed and order is rigidly maintained, though the chaos of Cooper's entourage is permitted to puncture the thought stream at any moment.

I had already seen Alice Cooper's 1975 extravaganza stage show, been granted my precious hour to chat, warned that Cooper will smile and be gracious, but underneath it all, would rather be almost anywhere than yattering in a hotel room. For the first time in almost two solid years of observing Cooper's antics tear respectability to smithereens, I wonder if Alice Cooper is worth the bother. Alice Cooper is, by his own admission, an industry, a corporation working towards becoming an institution. "I became Alice. I did all the press interviews because it was easier to sell one image than five. So I was the one who got up at eight in the morning while everyone else was sleeping. And deservedly, I am Alice. You don't have a choice, once you're in this position and the name is a household word, a question on a quiz show. You're un-American if you don't want that. That's our whole idea: to do something, do it well, have fun and make money." I guess the cash registers of America are telling me he is worth the bother.

Vince Furnier, now legally Alice, is a charming, articulate grown-up. Partial to playing Looney Tunes and the Mickey Mouse Club in his hotel room, the TV silliness only underscores the very concrete grasp Alice has of his position. He is the scheme of things, well-attended, every whim catered to by a seemingly endless flow of funds. Cooper in person is a far cry from the legendary decapitator of chickens. Rather, he's Mister Nice Guy. One cannot imagine him losing his temper while an outsider is around, unless he's in costume. At the same time, all this sugar ans spice tends to ring a little hollow. Cooper smiles with the same graciousness of a perpetual Academy Award winner, but is not manager Shep Gordon always one step behind the footlights, pulling at least a few strings?

Cooper's rise to stardom over the last 10 years has been a chartable success story, but was also an unguessable escalation. A man in his late twenties whose face shows more than a few effects of hard traveling, Cooper began his antics in an Arizona hight school band. Early pictures show a short-haired, traditionally attired high schooler, but, related Alice, the seeds of the showman were already in evidence. "We were doing this (a stage show) in 1965. We had to make our own props because we were broke. This show, 'Welcome to My Nightmare,' cost $400,000 to produce. We had a guy from Disneyland design all the props. If you're gonna be an institution you gotta go with the best. I want Alice Cooper to be like Barnum & Bailey Circus or like Halloween.

"I could take any band I've seen on 'In Concert', and in two weeks put them into a theatrical show. If you have that type of forethought, you start with a concept, look at what the band does and design it. It a band is corny, make them ultra corny. I'm a show designer as much as I'm a performer. The very first show I did I played from a bathtub. The band brought it out like Washington crossing the Delaware.

"We were really crazy. In 1966, we were wearing eye makeup. We'd go to the Ice Capade places and find old costumes and tear them up to wear. It got to be an in thing to leave Alice Cooper concerts in Hollywood..."

One person, at least, stayed til the end of the sets, and far beyond the dead-busted California days. Shep Gordon was an interested figure of the periphery of the music business when he saw the marketability of Cooper's gamy ensemble. They represented a look under the rock at the seamier side of entertainment, and Gordon swept the image to its limits. The early Cooper album show the fivesome in their torn-up gear, dripping in makeup, dissipation and challenge. Issued on Frank Zappa's Bizarre Records, the first and second Cooper offering didn't boast hit singles with catchy phrases. Rather, they stressed dark mumblings about things best left untouched, to the tun of lengthy electronic howls. For late 60's America, just emerging out of the peace/love/and good vibes era, Alice Cooper was tantalizing as the next weedy pathway to be explored.

The band switched labels, to Warner Bros. proper, and issued an album called "Killer," whose cover depicted Alice Cooper hanging from a noose. Hoo-boy, was this a move designed to widen the 'ol generation gap. (Its effect was underscored by the fact of a young boy killing himself via a noose a few years ago, thinking he would be just like Alice. Cooper has, indeed, maintained a Superman-like, immortal posture in the eyes many.) From "Killer" came a song that catapulted Alice Cooper into the big money bracket, giving him freedom while locking in his image at the same time. "Eighteen" was a teenage whine, the suppressed aggravation of a kid looking for something to do, watching his self- discipline shatter because he "don't know what I want." To this day, it's a rallying cry at Cooper concert, and one of the shows more uncomfortable stimulating moments.

It was the chicken rumor that put Cooper into the deepest pit of controversy. Did Alice Cooper really bite off the head of a chicken and suck the blood onstage? Or did he throw chickens out to the audience and stand back, a bit horrified as everyone's favorite child tore them to smithereens? After loads of hysterical, back and forth speculation, the latter account seems closest to true. Alice might fool around with a snake or two, but he'd rather gulp Budweiser than chicken blood. Still, the stunt gave Cooper's career another large push, one which sells the arenas while making behind-the-scenes work on huge step more complex.

"I really believe in sensationalism," Cooper claims seriously. "We get blamed for doing a lot of violence onstage but we don't do anything as violent as what's required reading for school. If anybody does a Macbeth or King Lear, those are bloody plays. We don't do anything as violent as "SWAT," that TV show, so I don't see why we're labeled violent. Of course, to be an American, you have to have a certain percentage of being violent. Our whole system is based on violence. And I'm just putting it onstage. But I don't take it seriously. I'm doing it on sort of a mock level. 99 per cent of the kids don't take it seriously, they know that Alice is up there having fun. My favorite actors were the villains, Bela Lugosi, Vincent Price. So I emulate that, because for every John Denver you have to have an Alice Cooper just to balance."

After a string of hit singles and gold albums, Alice Cooper could have denounced everything from God to Country and fans would be unstoppable. (Instead, he continually asserts his patriotism.) Each show exceeded the extravaganza level of the one which came before, until in 1973, Alice did a three month tour titled "Billion Dollar Babies." Then monied theme was more than incidental. Though, as in all of his shows, Alice is threatened onstage, here with a guillotine, something of a change was placed in the wind. Everyone in the Cooper organization was growing sensitized to continual assertions of bloodlust and violence, on the parts of both press and audience. In a few words, it was time to clean up the act, but very sneakily.

I worked on the "Billion Dollar Babies" tour as a cog in the huge Cooper machine, a press agent with the firm that was doing Alice's publicity. The organizational machine ran flawlessly. Alice Cooper was the size of a small firm, giving almost 50 people their immediate income, providing remuneration indirectly for hundreds more. When Alice flew from town to town it was questions from the newspapers, questions from the TV stations, wanting to know about the chicken stories, the snakes, the dresses, the makeup, and want exactly was Alice Cooper in terms of gender. As some of the more culturally radical publications stated they felt Cooper was selling out to the crowd, and forsaking his roots in the sinister, television newspeople sheepishly asked for tickets to the show for their children. they also, these people who were used to confronting mobsters and politicians without a flinch, confessed that they were somewhat awed by Alice Cooper and what should one ask of him. I had never before, or since, seen such an unsettling effect by rock music on a supposedly unflappable industry.

The action at Cooper concerts is provided by threats of what might happen as much as by anything occurring on the stage. In great clumps in 1973, to a much lesser extent in 1975, the aisles were clogged with teenies hallucinating on a variety of things, ready to believe Alice died and was reborn as the guillotine sliced his head off. In 1973, Cooper teased the audience to attach him, insulted them, leeringly fixed his eyes at some 14-year-old girl in the front row, believed himself in control. It wasn't always the case. In his excellent recollection of the second phase "Billion Dollar Babies" tour, journalist Bob Greene went onstage as part of the band, and chillingly observed how little it took to make that finely oiled system crackle. It took only a few ugly incidents to make Cooper realize how fine was the line that separated him from a mob who believed he was more chicken to devour. Things have changed.

"There are certain tricks you learn onstage about staging a show. You can tell when they're ready to break the barricade down. There are certain little tricks you have to cool them so that they don't even know why they're getting more relaxed. And there are certain times when the audience is low and you can do one little thing and immediately they're up. It's something you learn just by experience on the road. I can walk onstage and immediately know the attitude of the audience. That's my area, to keep them interested but not to have them riot. Too much work went into the show for them not to see it."

"Welcome to My Nightmare" is as much a television show as a concert. There's action happening around Cooper all the time, whether he's been surrounded by a huge rubber spider, or a group of dancers in imitating insects, or he's playing with a toybox, a sword, or any of a carload of other props. Not willing to run the risk of losing control, Alice Coper has put his rock'n'roll behind his entertainment, both literally onstage and in light of his total presentation. The original band is gone after ten years, replaced by some excellent session players. Why Michael Bruce, Neal Smith, Dennis Dunaway and Glen Buxton were not on the tour depends on whose story you wish to believe. Suffice it to say there are several sets of opinions.

The one constant is Alice Cooper. Alice is a superstar. He is enjoying all the benefits ten years of rock have given him, and his aspirations have brought him into close contact with a completely different strata of American entertainers. For a man who started out dead broke, with smeared makeup, as the butt of a million fag jokes, Alice Cooper is now chums with the likes of Bob Hope, Salvador Dali and Groucho Marx. Say Cooper, "You learn things from Paul Lynde, from Groucho Marx. There are only five or six people in the rock business that are great people, like Harry Nilsson, Ringo, McCartney, Lennon, but the others are just really boring. I don't get into partying all night, because I already did that."

Cooper's position is secure enough for him to renounce the world that elevated him in favor of the mainstream entertainers he obviously dotes on. Salvador Dali is fruity enough to be passed off as a sensible expression of Alice's craziness, but Bob Hope? What's happening instead is that Alice has proved strong enough to pull them along on his ride. The next step would have to be thousands of fans taking up golf as a hobby, following in Alice's footsteps, viewing the sport as the latest trends. But not if their fathers go out on the greens every Saturday...

The most dangerous confrontation Cooper has faced in any of the challenges to his career has been with his own image. A character as potent as Alice Cooper threatens to eat up the person inside the mask. Cooper does not walk around the streets in black leather, cracking the whip as any upstart who dares get in the way. Far from being either the neuter or ragidly sexual aggressor he has been typed as, cooper has maintained a relatively monogamous relationship with model Cindy Lang for over size years. He reacts with genuine concern to the minority of his fans that do take the death trip seriously, but refuses to get locked in to the high risk of portraying Alice Cooper 24 hours each day.

"I used to have that feeling, and finally divorced both of the roles that i play. I left Alice on stage. I don't chase people around with axes all day in the hotel. For some reason Alice doesn't even sound feminine any more. I get letters all the time that say, I had a son and i named him Alice, his middle name is Butch. I hope the audience realizes it's just a role, cause I don't take anything I do seriously.

"I can't watch 'In Concert' or 'Midnight Special,' they're just too boring."

If Alice takes anything seriously, and certainly his management does, it's to keep pulling in the dollars. Cooper made several million dollars on the "Billion Dollar Babies" tour, and has shown similar profits for "Welcome to My Nightmare." He cheerfully admits that he wouldn't know how to write a check these days, and at the same time mentions that his business arm invested in "California Split," "Shampoo," and "Funny Lady," all of which doesn't hurt when that harping minority of early fans scream sellout.

"Any artist that sits back and says it's not good art if you make money is bullshit. There was that old beatnik thing of, if it's successful it's not good, you have to be the underdog for it to be art. I don't believe in that word, art. There's no law against being commercial and at the same time being really interested and good at what you're doing, and getting imaginations going.

"The hardest part is waiting. You get to a hotel and wait all day in a little cube. That's part of the game plan. You are a commodity. In this position here, you are a piece of merchandise that gets sold. And then you remember that you have to stay human. The classic tragic case is Jim Morrison. He was always playing his character. He believed his magic too much. I believe in Alice, but I believe in Alice onstage. He was designed for the stage. He wasn't designed to go running around in society. He's just a character."

Alice Cooper will continue, because he's part of the American consciousness. Having made the transition to a household word, he may or may not pass into history, but they'll never forget him in Dubuque. And the music? I don't suppose in the long run, as long as he stands aside to let the crowd roar its approval.

(Originally published in the October/November 1975 issue of Modern Hi-Fi & Music magazine)