Article Database

Nothing's Shocking

Burning pyres of flame burst upward, searching with blazing orange heat, as beaded sweat glistens with the illumination that sweeps across a sea of faces. Adorned in black darkness, they chant, dancing the celebratory ritual of rock 'n' roll. Vibrant with rebelliousness, they are defiant, fueled by an exhilaration of being alive.

"It's not a concert, so much as it's like this big tribal ritual," offers Glen Danzig, elaborating on the communal spirit that elevates a theatrical rock show. "It's an event, some kind of thing that we're all involved in for the evening," he continues, categorizing what a good rock 'n' roll performance is supposed to be.

The parallel between Celtic culture and the imagery of extreme hard rock theatre is seamless, similar in infinite respects. In much the same manner that ancient Celts would draw life from flame, cloaking themselves form the harsh onset of winter, so do metal fans absorb the energy of ghoulish excitement from a misunderstood conservatism that would attempt to smother the thrill of being alive.

The origin of Halloween can be traced in direct lineage from Samhain, the Celtic New Year that marked the transition of the seasons, as well as representing rebirth of the spirit and rejuvenation of the soul. Traditionally celebrated October 31, it was also believed to be the solitary night when existential barriers were weakest, when departed spirits roamed the world of the living - Much to the consternation of Christianity.

"The church is always trying to away with Halloween," insist Danzig, who points to the Seventh Century, when Pope Benedict IV attempted to assimilate the Celtic festival with a similar holiday, albeit one sanctioned by the church. "Since the old days, they've never been able to do away with it," defies the dark singer. "I mean, that's why they started called Samhain 'Halloween,' to incorporate this old Pagan ritual and get rid of it. They still can't stop it, and it just irritates 'em so much."

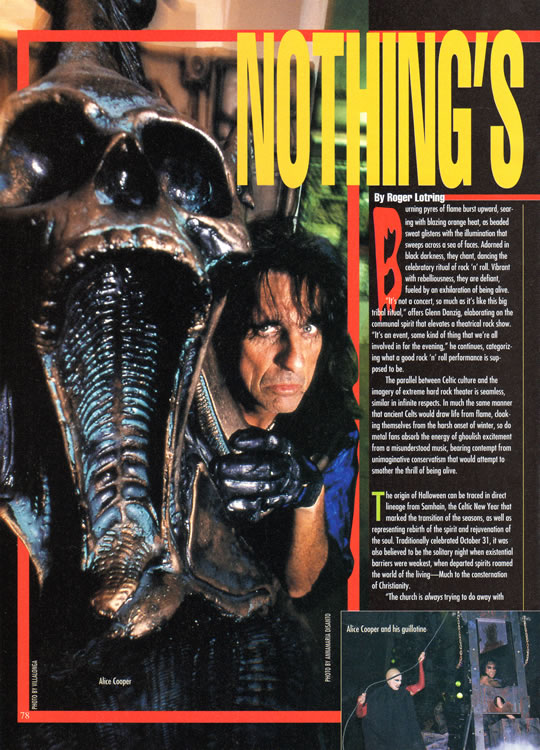

"When I was a kid, you couldn't wait 'til Halloween, because that was really just the most fun," recalls Alice Cooper, for whom the real entertainment was the collective imagination. "You actually got a picture of what people were really like," he says, pointing to the example of "this guy who you thought was a geek, who would show up in some really insane costume. You'd have a whole new respect for this guy," he says with a laugh.

In spite of the purity of the traditional origins of Halloween, Satanic imagery and damnation have perpetually been branded upon the holiday, and similarly upon rock 'n' roll, in equally unsuccessful attempts to purge a defiant lifestyle. But demonic intonation in rock has evolved from an ancestry of superstition folklore. Just as rock 'n' roll was derived form bluesy musical inspiration, so has it inherited the stigmatic curse of being labeled as "Devil's music." Hell was believed to be a purgatory of souls, commerce of the Devil, in exchange for the trappings of musical success. The legend of Blues folklore has perpetuated over the course of years, from the melancholy wail of Robert Johnson - who supposedly sold his soul to Lucifer during a midnight pact at the crossroads - to the bemoaning wail of Robert Plant, repentant over the legendary tale of Led Zeppelin likewise exchanging their salvation for musical fortune. But the striking similarity between the denouncement of Celtic mythology and the demonic temptations of rock 'n' roll, both painted by misguided moralism, is not without irony. Oddly enough, of those who epitomize the darkness of theatrical rock, many of their influences as reactionary as adolescent religious indoctrination - The likes of Marilyn Manson, Blackie Lawless, and Alice Cooper.

The apocalyptic lyrical horror of Black Sabbath - a band who recognized the capitalistic brilliance of fright - may have first stirred the imagination of the audience, but the visual aspect of horrific theatrics began to develop much earlier, notably with Screamin' Jay Hawkins, whose grandiose stage entrance by rising from a coffin sparked curiosity. The singer employed macabre theatrical elements as part of his performance, incorporating skulls, snakes and shrunken heads. But despite seemingly dark imagery, he tended to represent more of a campy ethnicity, and his portrayal of voodoo, popularized by the hit "I Put A Spell On You," was more akin in appeal to vaudeville. Instead, it was the English madman Screaming Lord Sutch who brought a more genuine believability to the genre, anglicized by his evident fascination with Jack The Ripper, among others. With longish hair dyed green, Sutch developed a crude style of performance theatre that incorporated simulated visuals that included stabbings and mutilations, not unlike that of Alice Cooper of W.A.S.P.

"He couldn't sing worth a damn," remarks W.A.S.P. frontman Blackie Lawless, who nonetheless found himself entranced during adolescence by Sutch, scouring rock magazines for photographs. But despite the musical limitations, Lawless says he had some great ideas, praising the singer who committed suicide by hanging in 1999. "He was taking it to a point where it was far more serious than Screamin' Jay Hawkins."

But the outlandish novelty of Hawkins, along with the simulated brutality of Lord Sutch, ultimately came together as a band that would influence a generation: Alice Cooper. By incorporating stunning visual imagery with cleverly twisted lyrics and grandiose music, the Alice Cooper Band literally built the cornerstone of the genre of theatrical rock.

For Cooper, the vocalist who purposefully refers to Alice as a character in the third person, the cue was taken from Zorro, as well as from Bernardo, the leader of the Sharks from West Side Story.

"I have no idea why the band was so into West Side Story," says Cooper of the early infatuation with the Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim musical. "But when I started putting Alice together, I just connected with those people. I saw the character of Bernardo as being the guy I wanted to be - Dark hair, kind of cool. And Zorro, he's kind of dark, and nobody knows anything about him." Certainly, the combination bore a certain innate sense of debonair within Alice Cooper, an evil charm with which the singer readily agrees, qualifying the character as "debonair, to the point of being arrogant. He was in your face, and he was an obvious villain. But he was sort of funny, kind of nasty... and entertaining!" Cooper laughs with a fondness for his alter ego.

But Alice Cooper also reflected a resemblance to Arthur Brown, the god of hellfire whose hit "Fire" from The Crazy World of Arthur Brown marked an early experimentation with pyrotechnical theatrics. "If you look at it, in all honesty, that record was what Alice later did with Welcome To My Nightmare," explains Lawless, noting that, "There's more than just a few similarities, but it was a pretty good pattern for trying to do that kind of presentation."

For Cooper, whose new Dragontown disc completes a musical trilogy that began with The Last Temptation of Alice Cooper and Brutal Planet, the inventiveness that defined the entire genre was natural in its evolution. "The very first time we ever performed, there was a guillotine onstage," he says, recounting an ornamental prop at a high school dance. "To me, it just felt normal, and I liked the audience's reaction to it. It wasn't nice, it was fascinating. When I got the idea that the audience was just a little bit put off, but almost charmed by what we did, then we did it more."

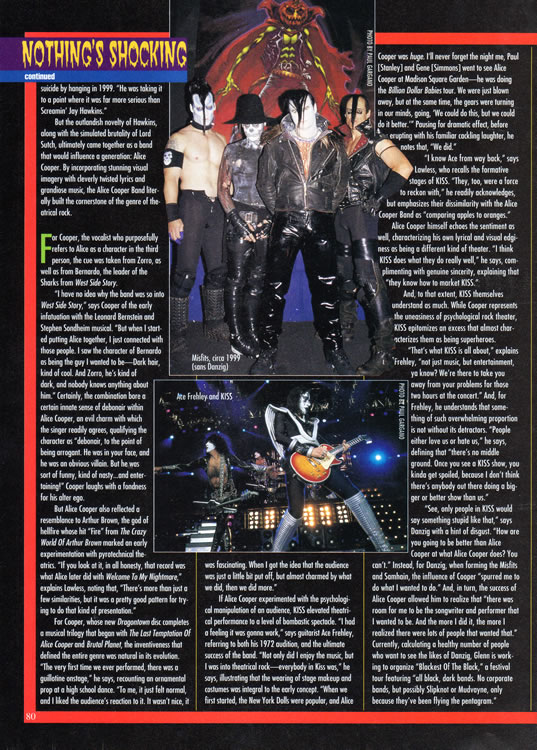

If Alice Cooper experimented with the psychological manipulation of an audience, KISS elevated theatrical performance to a level of bombastic spectacle. "I had a feeling it was gonna work," says guitarist Ace Frehley, referring to both his 1972 audition, and the ultimate success of the band. "Not only did I enjoy the music, but I was into theatrical rock - everybody in Kiss was," he says, illustrating that the wearing of stage makeup and costume was integral to the early concept. "When we first started, the New York Dolls were popular, and Alice Cooper was huge. I'll never forget the night me, Paul [Stanley] and Gene [Simmons] went to see Alice Cooper at Madison Square Garden - he was doing the Billion Dollar Babies tour. We were just blown away, but at the same time, the gears were turning in our minds, going, 'We could do this, but we could do it better.'" Pausing for dramatic effect, before erupting with his familiar cackling laughter, he notes that, "We did."

"I know Ace from way back," says Lawless, who recalls the formative stages of KISS. "They, too, were a force to reckon with," he readily acknowledges, but emphasizes their dissimilarity with the Alice Cooper Band as "comparing apples to oranges."

Alice Cooper himself echoes the sentiment as well, characterizing his own lyrical and visual edginess as being a different kind of theater. "I think KISS does what they do really well," he says, complimenting with genuine sincerity, explaining that "they know how to market KISS."

And, to that extent, KISS themselves understand as much. While Cooper represents the uneasiness of psychological rock theater, KISS epitomizes as excess that almost characterizes them as being superheroes.

"That's what KISS is all about," explains Frehley, "not just music, but entertainment, ya know? We're there to take you away from your problems for those tow hours at the concert." And, for Frehley, he understands that something of such overwhelming proportion is not without its detractors. "People either love us or hate us," he says, defining that "there's no middle ground. Once you see a KISS show, you kinda get spoiled, because I don't think there's anybody out there doing a bigger or better show than us."

"See, only people in KISS would say something stupid like that," says Danzig with a hint of disgust. "How are you going to be better than Alice Cooper at what Alice Cooper goes? You can't." Instead, for Danzig, when forming the Misfits and Samhain, the influence of Cooper "spurred me to do what I wanted to do." And, in turn, the success of Alice Cooper allowed him to realize that "there was room for me to be the songwriter and performer that I wanted to be. And the more I did it, the more I realized there were lots of people that wanted that." Currently, calculating a healthy number of people who want to see the like of Danzig, Glenn is working or organize "Blackest Of The Black," a festival tour featuring "all black, dark bands. No corporate bands, but possibly Slipknot or Mudvayne, only because they've been flying the pentagram."

"I loved the Misfits!" enthuses Alice. "I was fascinated by these guys. I mean, they had such great style." As suggested by their name, the Misfits were anomaly. Routinely categorized as punk, they overtly visual band presided over a secret society marked by an eerie, ghoulish figure, punctuated by songs that were exhilarating bursts of anarchistic dirge. Shrouded in mystery, as well as the adulation of their Fiend Club fans, the Misfits' love of horror film imagery manifested itself in crude, yet theatrical stage productions that encompassed an obsession with the B-movie genre.

But for Danzig, Halloween as a youth was celebration of mischief. "Me and my friends, we'd go around three or four time," he says, laughing at the recollection of trick or treating as kids. "We'd go out and do the neighborhood, then we'd go back as something different, like we'd throw a sheet over our head. But the second or third time, people were like, 'You guys were around already!l" But his maturation is still marked by a deviously mischievous mind. Remembering the Misfits' Whisky A Go Go performance in Hollywood, Danzig recalls terrorizing members of a young Motley Crue. "They had come to watch the soundcheck, but they we in, like, high heels. I remember me and Henry [Rollins] chasing them out the door, halfway up the street," he giggles. "After they say the Misfits that night, they put pentagrams on all their stuff and changed to the darker side - was was probably the best Motley Crue."

Prior to Motley Crue, perhaps the earliest theatrical horror band on the Sunset Strip was Sister, a band that presented the ghoulish imagery of Alice Coper and KISS, together with an occult fascination. Formed by Blackie Lawless before the advent of W.A.S.P., Sister supposedly also included bassist Nikki Sixx for a brief time. By incorporating the pentagram and occult-influenced theatrics, Sixx founded Motley Crue, shocking complacency with an admirable ability as a songwriter, nearly as much as by the spectacle of a destructive lifestyle.

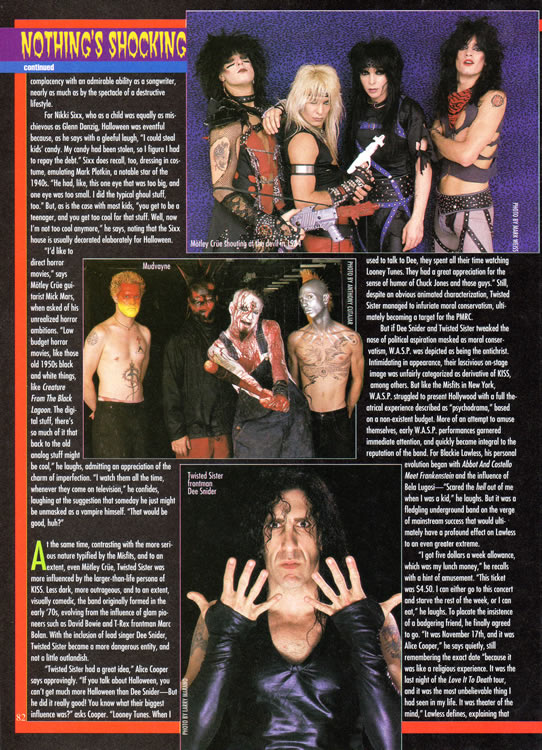

For Nikki Sixx, who as a child was equally as mischievous as Glenn Danzig, Halloween was eventful, as he says with a gleeful laugh, "I could steal kids' candy. My candy had been stolen, so I figure I had to repay the debt." Sixx does recall, too, dressing in costume, emulating Mark Plotkin, a notable star of the 1940s. "He had, like, this one eye that was too big, and one eye was too small. I did that typical ghoul stuff, too." But, as is the case with most kids, "you get to be a teenager, and you get too cool for that stuff. Well, now I'm not too cool anymore," he says, noting that the Sixx house is usually decorated elaborately for Halloween.

"I'd like to direct horror movies," says Motley Crue guitarist Mick Mars, when asked of his unrealized horror ambitions. "Low budget horror movies, like those old 1950's black and white things, like Creature From The Black Lagoon. The digital stuff, there's so much of it that back to old analog stuff might be cool, he laughs, admitting an appreciation of the charm of imperfection. "I watch them all the time, whenever they come on television," he confides, laughing at the suggestion that someday he just might be unmasked as a vampire himself. "That would be good, huh?"

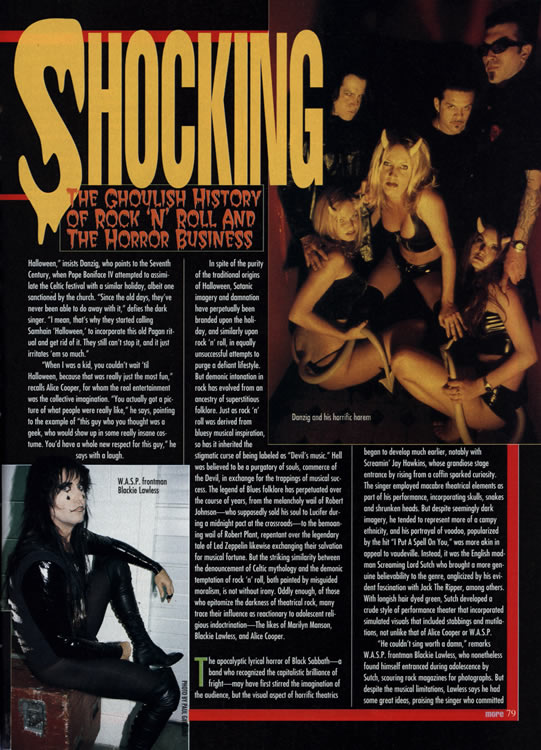

At the same time, contrasting with the more serious nature typified by the Misfits, and to an extent, even Motley Crue, Twisted Sister was more influenced by the larger-than-life persona of KISS. Less dark, more outrageous, and to an extent, visually comedic, the band originally formed in the early '70s, evolving from the influence of glam pioneers such as David Bowie and T-Rex frontman Marc Bolan. With the inclusion of lead singer Dee Snider, Twisted Sister became a more dangerous entity, and not a little outlandish.

"Twisted Sister had a great idea," Alice Cooper says approvingly. "If you talk about Halloween, you can't get much more Halloween than Dee Snider--But he did it really good! You know what their biggest influence was?" asks Cooper. "Luney Tunes. When I used to talk to Dee, they spent all their time watching Luney Tunes. They had a great appreciation for the sense of humor of Chuck Jones and those guys." Still, despite an obvious animated characterization, Twisted Sister managed to infuriate moral conservatism, ultimately becoming a target for the PMRC.

But if Dee Snider and Twisted Sister tweaked the nose of political aspiration masked as moral conservatism, W.A.S.P. was depicted as being the antichrist. Intimidating in appearance, their lascivious on-stage image was unfairly categorized as derivative of KISS, among others. But like the Misfits in New York, W.A.S.P. struggled to present Hollywood with a full theatrical experience described as "psychodrama," based on a non-existent budget. More of an attempt to amuse themselves, early W.A.S.P. performances garnered immediate attention, and quickly became integral to the reputation of the band. For Blackie Lawless, his persona began with Abbot And Costello Meets Frankenstein and the influence of Bela Lugosi--"Scared the hell out of me with I was a kid," he laughs. But it was a fledgling underground band on the verge of mainstream success that would ultimately have a profound effect on Lawless to an even greater extreme.

"I got five dollars a week allowance, which was my lunch money," he recalls with a hint of amusement. "This ticket was $4.50. I can either go to this concert and starve the rest of the week, or I can eat," he laughs. To placate the insistence of a badgering friend, he finally agreed to go. "It was November 17th, and it was Alice Cooper," he says quietly, still remembering the exact date "because it was like a religious experience. It was the last night of the Love It To Death tour, and it was the most unbelievable thing I had seen in my life. It was theater of the mind," Lawless defines, explaining that "they were trying to worm their way into your year, and it worked like a charm. It really left an impression on me, because three days went by, and I couldn't eat, I couldn't sleep... I kept seeing that show over and over in my head."

"Did I ever see anything where I said, 'We could do that better?'" he asks rhetorically, having recently been on tour for the Unholy Terror album. "Nothing," he punctuates, "could ever be better than what that was. I thought K.F.D was as good," he says of the allegorical symbolism of politically raped moralism that was his own band's 1997 European tour, "but it wasn't better."

"I just never got it," ways Alice Cooper of W.A.S.P. with somewhat forced diplomacy. "There was nothing clever about it. I could show you videos of me, and show you Blackie Lawless doing exactly the same thing. It wasn't even just a little bit of a copy, it was word-for-word."

"I never really talked about this before," says Lawless of the resentment felt by Alice Cooper toward him. "He would get really angry with me," says W.A.S.P.'s creative force, speaking thoughtfully about the bitterness of Cooper. "He said I never gave him credit. And the reason I never gave him credit," he says, in spite of the admitted influence of the band during his formative years, "is because I was angry with him. When the band broke up and he did Welcome To My Nightmare, he never gave that [original] band credit, and that really rubbed me the wrong way. It was that band, and the way they interacted together, that make this incredible energy come off the stage. I don't care if it was all his ideas or not, when you saw the band the way they put it together, no one person could do that by themself."

Still, when asked on ideal bill for an imaginary tour of theatrical bands, he responds quickly with instinctive sureness: "The Love It To Death Alice Cooper, the first album KISS, and the first album W.A.S.P."

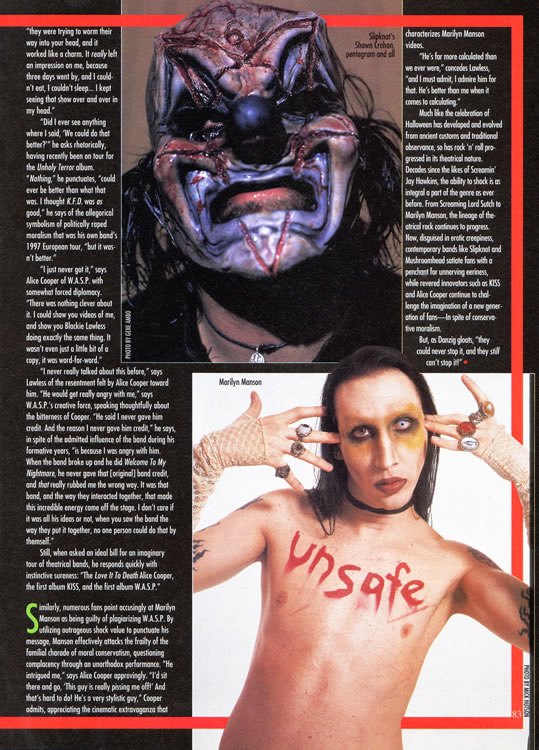

Similarly, numerous fans point accusingly at Marilyn Manson as being guilty of plagiarizing W.A.S.P. By utilizing outrageous shock value to punctuate his message, Manson effectively attacks the frailty of the familial charade of moral conservatism, questioning complacency through an unorthodox performance. "He intrigued me," says Alice Cooper approvingly. "I'd sit there and go, 'This guy is really pissing me off!' And that's hard to do! He's a very stylistic guy," Cooper admits, appreciating the cinematic extravaganza that characterizes Marilyn Manson videos.

"He's far more calculated than we ever were," concedes Lawless, "and I must admit, I admire him for that. He's better than me when it comes to calculating.

Much like the celebration of Halloween has developed and evolved from ancient customs and traditional observance, so has rock 'n' roll progressed in its theatrical nature. Decades since the like of Screamin' Jay Hawkins, the ability to shock is as integral a part of the genre as ever before. From Screamin Lord Sutch to Marilyn Manson, the lineage of the theatrical rock continues to progress. Now, disguised in erotic creepiness, contemporary bands like Slipknot and Mushroomhead satiate fans with a penchant for unnerving eeriness, while revered innovators such as KISS and Alice Cooper continue to challenge the imagination of a new generation of fans--In spite of conservative moralism.

But, as Danzig gloats, "they could never stop it, and they still can't stop it!"