Article Database

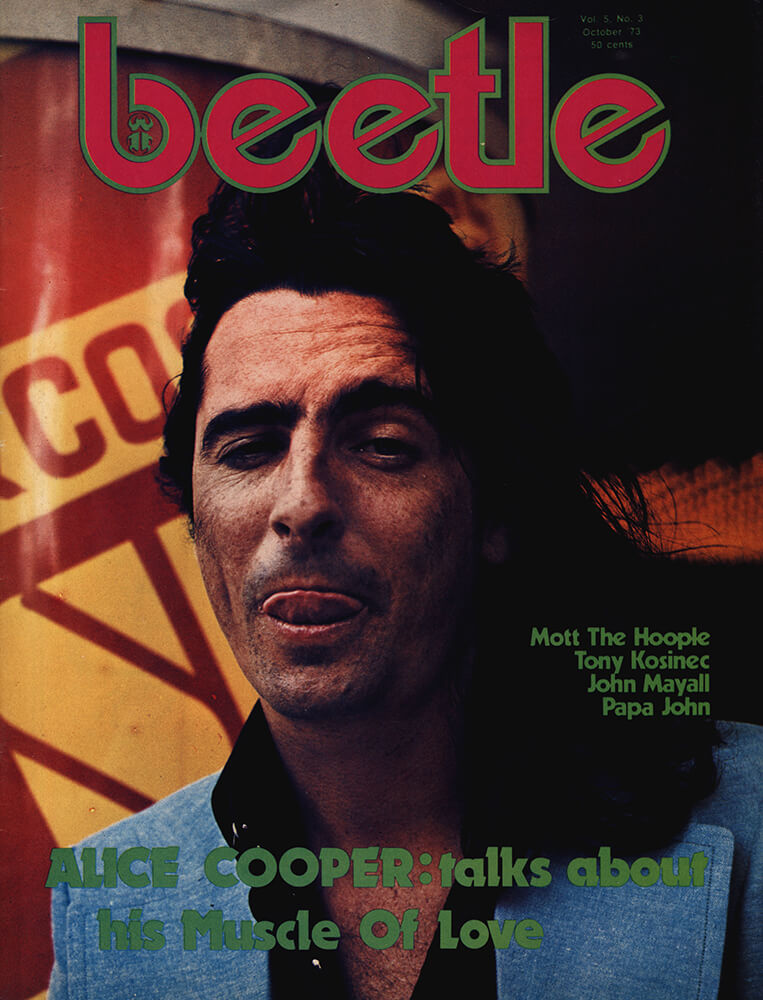

Alice Cooper's Muscle Of Love

Alice Cooper has managed to go from being one of the most neglected, laughed at bands in history to one of the richest, laughed at bands in history. Always willing to tell little white lies for sensationalism, Alice is a journalists nightmare. We invite you to come along and share the nightmare.

Toronto is a rather large city, both in terms of population and the amount of land covered by its concrete, steel and glass. With incredible phallic towers rising high over the heads of the citizenry, the city is clean and well-planned. Visitors continually comment on the cleanliness of Toronto, especially the immaculate state in which the subways and transit vehicles are kept. But the telltale signs of Americanization are becoming increasingly visible. While the Stars and Stripes may not yet be flying at City Hall, the crime and violence rates are both on the upswing, something that has many citizens in a moral stew. But they have yet to complain about Alice Cooper, the ultimate end result of American society.

For two weeks, Alice and his band of femmy hitmen have been sitting under their very noses, residing at one of the cities best hotels, walking the streets and enjoying the sights. Alice and his boys have long been a large draw in Toronto. The band considers the town its home-away-from-home, perhaps because it's as dull as Phoenix, Arizona, their original hometown, but more likely because they have spent a great deal of time here. While the band was struggling and frequently bombing in America in 1969, Toronto offered sanctuary to the shock-rockers. They appeared in the city four times in 1969, each time drawing an impressive crowd, though two of the dates were pop festivals. America was offended by the chickens, and broomsticks, trademarks of Alice's early act. Canada was awed and even amused.

The production company that has handled the studio chores for Alice's last four albums, Nimbus 9, is a Canadian company. At the helm of the organization is Jack Richardson, more than slightly rotund producer of the Guess Who and Poco, among others. Richardson and his company are making good money these days, certainly more money than most people expected to come his way when he was struggling to get the Guess Who off the ground about five years ago. And the presence of big money is obvious. Richardson is in the midst of assembling what could well be the city's best studio. The interior design is modern with small signs of the Cooper band's existence and importance strewn strategically about the corridors. Although the control board was hot installed at the time of Alice's two week stay, it was not necessary. Alice and the boys were here for two major reasons. Pre-production work on the quintet's new album had started and the band was busy rehearsing in which will eventually be the Nimbus 9 studio. Also, Alice Cooper has garnered four Canadian platinum albums, a true sign of their ever-increasing popularity in the north country, and Alice meant to collect them.

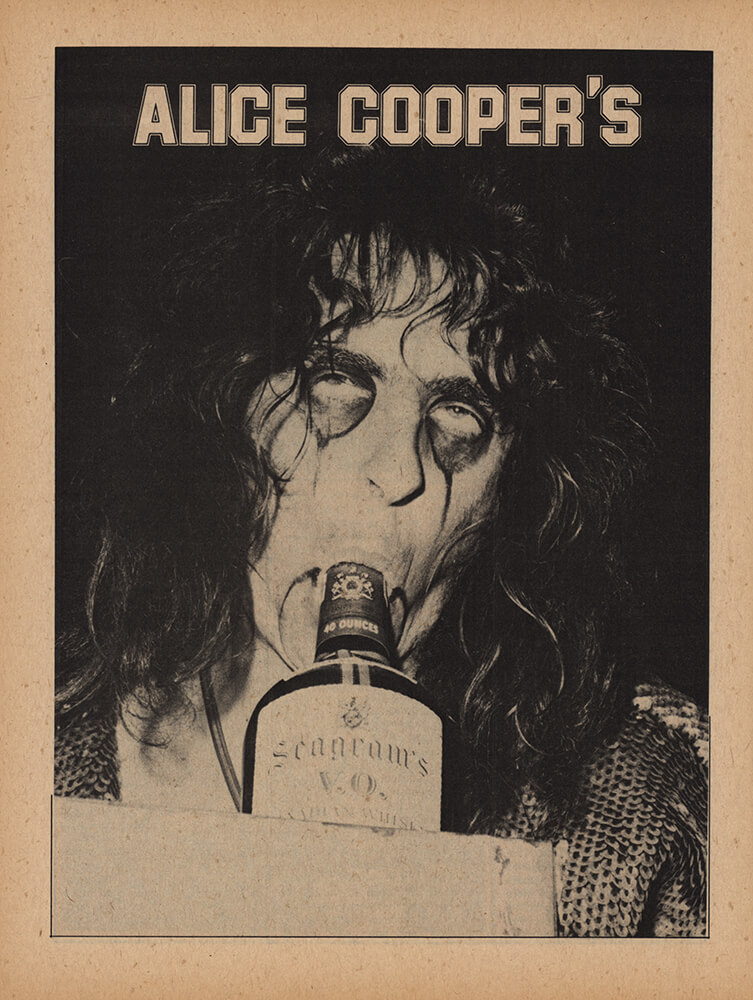

A color television set sits in one of the studio's corridors, next to the pinball machine which is constantly in use. The refrigerator is stocked to the gills with Budweiser, the king of beers, and another few crates of the foamy brine sit beside the icebox waiting to be chilled. A vamped-up mannequin stands in a corner wearing a feather boa and leery smile. Someone has glued some hair in a strategically pubic area and the dummy's right breast sports a button reading "Try A Virgin" in huge letters. It is only with a second look that one notices the tiny letters underneath the brazen slogan..."Island."

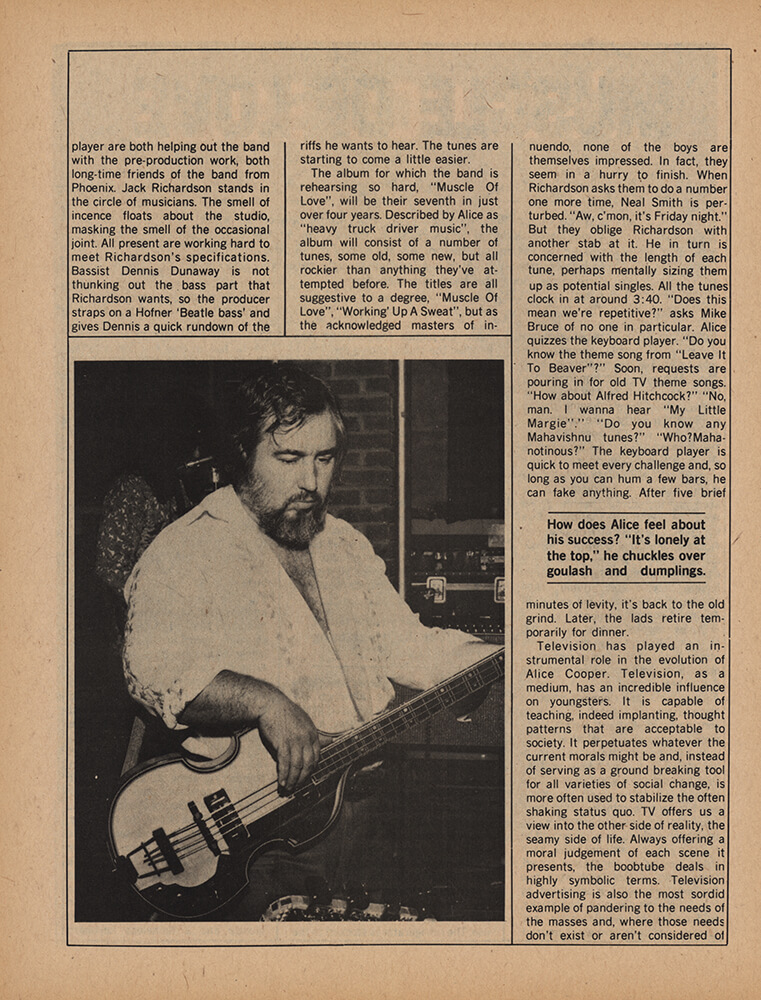

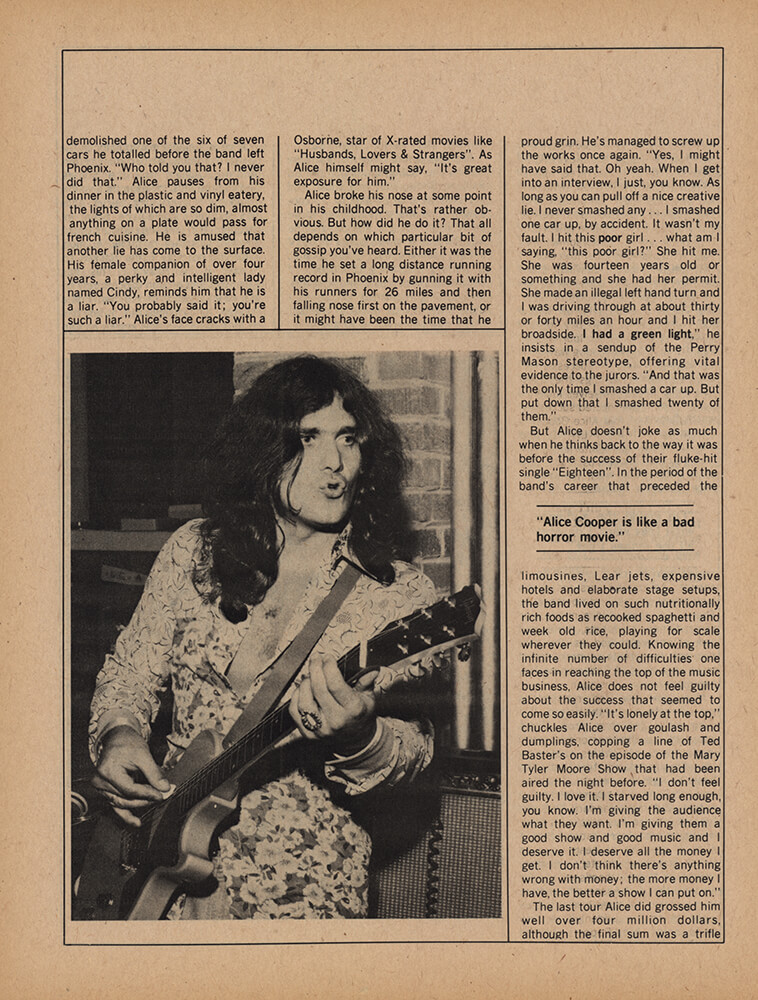

A thunderous sound erupts from somewhere in the building and fights its way through the double doors at the end of the corridor. Walking through the double doors, one is instantly in what will soon be the studio's control room. Through another set of doors one is immediately slapped in the face by the churning, primal rock that the band is laying down for their next album. Alice sits sandwiched between two amps and cabinets, a lyric sheet in his lap, cradling a half-empty can of Bud in his long-fingered hands. Decked out in a white t-shirt and jeans, Alice appears to be the complete antithesis of his onstage persona. Drummer Neal Smith sits across the room hammering away at an impressive array of shells and skins which is in fact only a fraction of the kit he uses in concert. Mike Bruce, the muscular, athletic looking guitarist, seems more than a little out of place amid the limp-wristed pretties. Mike and a thin, blonde guitarist are sharing the axeman responsibilities as Glen Buxton, the band's regular lead guitarist, is inexplicably absent. The blonde and a nameless keyboard player are both helping out the band with the pre-production work, both long-time friends of the band from Phoenix. Jack Richardson stands in the circle of musicians. The smell of incense floats about the studio, masking the smell of the occasional joint. All present are working hard to meet Richardson's specifications. Bassist Dennis Dunaway is not thunking out the bass part that Richardson wants, so the producer straps on a Hofner 'Beatle bass' and gives Dennis a quick rundown of the riffs he wants to hear. The tunes are starting to come a little easier.

The album for which the band is rehearsing so hard, "Muscle Of Love", will be their seventh in just over four years. Described by Alice as "heavy truck driver music", the album will consist of a number of tunes, some old, some new, but all rockier than anything they've attempted before. The titles are all suggestive to a degree, "Muscle Of Love", "Working' Up A Sweat", but as the acknowledged masters of innuendo, none of the boys are themselves impressed. In fact, they seem in a hurry to finish. When Richardson asks them to do a number one more time, Neal Smith is perturbed. "Aw, c'mon, it's Friday night." But they oblige Richardson with another stab at it. He in turn is concerned with the length of each tune, perhaps mentally sizing them up as potential singles. All the tunes clock in at around 3:40. "Does this mean we're repetitive?" asks Mike Bruce of no one in particular. Alice quizzes the keyboard player. "Do you know the theme song from "Leave It To Beaver"?" Soon, requests are pouring in for old TV theme songs. "How about Alfred Hitchcock?" "No, man. I wanna hear "My Little Margie"." "Do you know any Mahavishnu tunes?" "Who? Maha-notinous?" The keyboard player is quick to meet every challenge and, so long as you can hum a few bars, he can fake anything. After five brief minutes of levity, it's back to the old grind. Later, the lads retire temporarily for dinner.

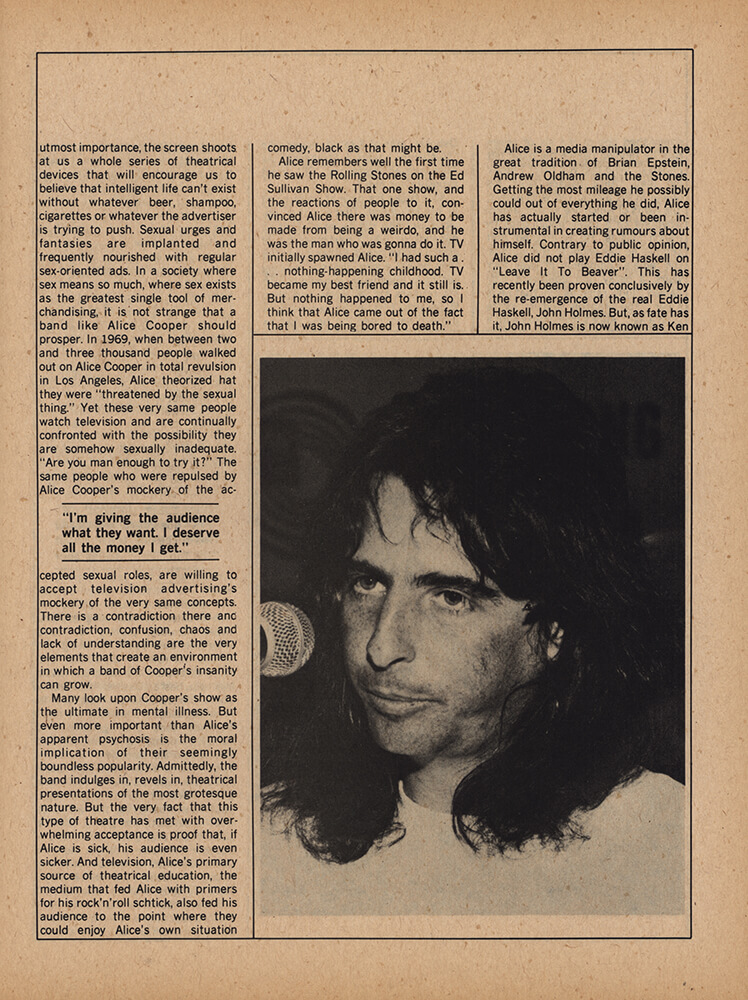

Television has played an instrumental role in the evolution of Alice Cooper. Television, as a medium, has an incredible influence on youngsters. It is capable of teaching, indeed implanting, thought patterns that are acceptable to society. It perpetuates whatever the current morals might be and, instead of serving as a ground breaking tool for all varieties of social change, is more often used to stabilize the often shaking status quo. TV offers us a view into the other side of reality, the seamy side of life. Always offering a moral judgement of each scene it presents, the boobtube deals in highly symbolic terms. Television advertising is also the most sordid example of pandering to the needs of the masses and, where those needs don't exist or aren't considered of utmost importance, the screen shoots at us a whole series of theatrical devices that will encourage us to believe that intelligent life can't exist without whatever beer, shampoo, cigarettes or whatever the advertiser is trying to push. Sexual urges and fantasies are implanted and frequently nourished with regular sex-oriented ads. In a society where sex means so much, where sex exists as the greatest single tool of merchandising, it is not strange that a band like Alice Cooper should prosper. In 1969, when between two and three thousand people walked out on Alice Cooper in total revulsion in Los Angeles, Alice theorized that they were "threatened by the sexual thing." Yet these very same people watch television and are continually confronted with the possibility they are somehow sexually inadequate. "Are you man enough to try it?" The same people who were repulsed by Alice Cooper's mockery of the'accepted sexual roles, are willing to accept television advertising's mockery of the very same concepts. There is a contradiction there and contradiction, confusion, chaos and lack of understanding are the very elements that create an environment in which a band of Cooper's insanity can grow.

Many look upon Cooper's show as the ultimate in mental illness. But even more important than Alice's apparent psychosis is the moral implication of their seemingly boundless popularity. Admittedly, the band indulges in, revels in, theatrical presentations of the most grotesque nature. But the very fact that this type of theatre has met with overwhelming acceptance is proof that, if Alice is sick, his audience is even sicker. And television, Alice's primary source of theatrical education, the medium that fed Alice with primers for his rock'n'roll schtick, also fed his audience to the point where they could enjoy Alice's own situation comedy, black as that might be.

Alice remembers well the first time he saw the Rolling Stones on the Ed Sullivan Show. That one show, and the reactions of people to it, convinced Alice there was money to be made from being a weirdo, and he was the man who was gonna do it. TV initially spawned Alice. "I had such a… nothing-happening childhood. TV became my best friend and it still is. But nothing happened to me, so I think that Alice came out of the fact that I was being bored to death."

Alice is a media manipulator in the great tradition of Brian Epstein, Andrew Oldham and the Stones. Getting the most mileage he possibly could out of everything he did, Alice has actually started or been instrumental in creating rumours about himself. Contrary to public opinion, Alice did not play Eddie Haskell on "Leave It To Beaver". This has recently been proven conclusively by the re-emergence of the real Eddie Haskell, John Holmes. But, as fate has it, John Holmes is now known as Ken demolished one of the six of seven cars he totalled before the band left Phoenix. "Who told you that? I never did that" Alice pauses from his dinner in the plastic and vinyl eatery, the lights of which are so dim, almost anything on a plate would pass for french cuisine. He is amused that another lie has come to the surface. His female companion of over four years, a perky and intelligent lady named Cindy, reminds him that he is a liar. "You probably said it; you're such a liar." Alice's face cracks with a Osborne, star of X-rated movies like "Husbands, Lovers & Strangers". As Alice himself might say, "It's great exposure for him."

Alice broke his nose at some point in his childhood. That's rather obvious. But how did he do it? That all depends on which particular bit of gossip you've heard. Either it was the time he set a long distance running record in Phoenix by gunning it with his runners for 26 miles and then falling nose first on the pavement, or it might have been the time that he proud grin. He's managed to screw up the works once again. "Yes, I might have said that Oh yeah. When I get into an interview, I just, you know. As long as you can pull off a nice creative lie. I never smashed any... I smashed one car up, by accident. It wasn't my fault. I hit this poor girl... what am I saying, "this poor girl?" She hit-me. She was fourteen years old or something and she had her permit. She made an illegal left hand turn and I was driving through at about thirty or forty miles an hour and I hit her broadside. I had a green light," he insists in a sendup of the Perry Mason stereotype, offering vital evidence to the jurors. "And that was the only time I smashed a car up. But put down that I smashed twenty of them."

But Alice doesn't joke as much when he thinks back to the way it was before the success of their fluke-hit single "Eighteen". In the period of the band's career that preceded the limousines, Lear jets, expensive hotels and elaborate stage setups, the band lived on such nutritionally rich foods as recooked spaghetti and week old rice, playing for scale wherever they could. Knowing the infinite number of difficulties one faces in reaching the top of the music business, Alice does not feel guilty about the success that seemed to come so easily. "It's lonely at the top," chuckles Alice over goulash and dumplings, copping a line of Ted Baxter's on the episode of the Mary Tyler Moore Show that had been aired the night before. "I don't feel guilty. I love it. I starved long enough, you know. I'm giving the audience what they want. I'm giving them a good show and good music and I deserve it. I deserve all the money I get. I don't think there's anything wrong with money; the more money I have, the better a show I can put on."

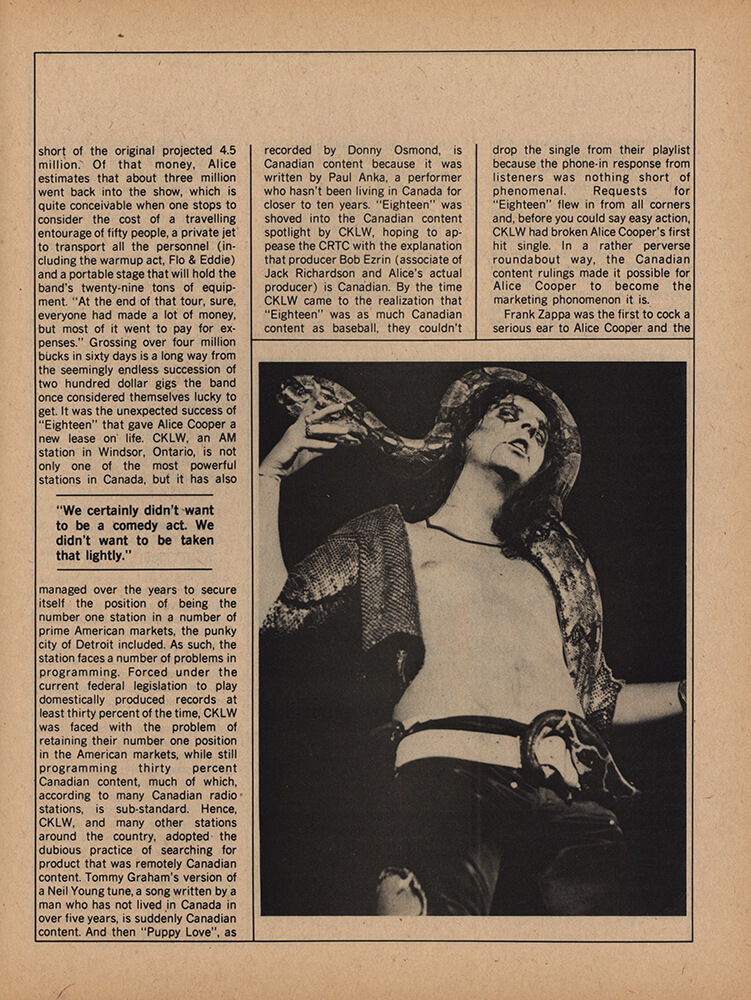

The last tour Aiice did grossed him well 'over four million dollars, although the final sum was a trifle short of the original projected 4.5 million. Of that money, Alice estimates that about three million went back into the show, which is quite conceivable when one stops to consider the cost of a travelling entourage of fifty people, a private jet to transport all the personnel (including the warmup act, Flo & Eddie) and a portable stage that will hold the band's twenty-nine tons of equipment. "At the end of that tour, sure, everyone had made a lot of money, but most of it went to pay for expenses." Grossing over four million bucks in sixty days is a long way from the seemingly endless succession of two hundred dollar gigs the band once considered themselves lucky to get. It was the unexpected success of "Eighteen" that gave Alice Cooper a new lease on life. CKLW, an AM station in Windsor, Ontario, is not only one of the most powerful stations in Canada, but it has also managed over the years to secure itself the position of being the number one station in a number of prime American markets, the punky city of Detroit included. As such, the station faces a number of problems in programming. Forced under the current federal legislation to play domestically produced records at least thirty percent of the time, CKLW was faced with the problem of retaining their number one position in the American markets, while still programming thirty percent Canadian content, much of which, according to many Canadian radio stations, is substandard. Hence, CKLW, and many other stations around the country, adopted the dubious practice of searching for product that was remotely Canadian content. Tommy Graham's version of a Neil Young tune, a song written by a man who has not lived in Canada in over five years, is suddenly Canadian content. And then "Puppy Love", as recorded by Donny Osmond, is Canadian content because it was written by Paul Anka, a performer who hasn't been living in Canada for closer to ten years. "Eighteen" was shoved into the Canadian content spotlight by CKLW, hoping to appease the CRTC with the explanation that producer Bob Ezrin (associate of Jack Richardson and Alice's actual producer) is Canadian. By the time CKLW came to the realization that "Eighteen" was as much Canadian content as baseball, they couldn't drop the single from their playlist because the phone-in response from listeners was nothing short of phenomenal. Requests for "Eighteen" flew in from all corners and, before you could say easy action, CKLW had broken Alice Cooper's first hit single. In a rather perverse roundabout way, the Canadian content rulings made it possible for Alice Cooper to become the marketing phenomenon it is.

Frank Zappa was the first to cock a serious ear to Alice Cooper and the first to consider their potential as something more than a bunch of novelty act closet queens. But after a relatively short amount of time, a rift grew between Zappa and the Cooper clan. Although reports on the causes of the split are conflicting, with one story blaming Frank's narrowmindedness concerning drugs (something that Alice himself feels strongly about) and another revealing that Frank's interest in the band was anything but a musical one, Alice maintains that even Frank, the musical genius credited with bringing Alice to the forefront, was more interested in the band's potential as a comedy act. "I really don't know where Frank was at. He had all these acts that he was trying to produce as comedy acts, and we certainly didn't want to be a comedy act. There was the split right there. We didn't want to be taken that lightly, you know? So we just drifted apart. There were no harsh words or anything, we just drifted apart. I mean, he's still a friend. That's not to say that we don't have some humor in the act, but it's tongue in cheek humor. Alice Cooper is like a bad horror movie. You say, "Aw, c'mon." But at the same time, there are points in that movie that scare you to death. And that's always been fun for me. Whenever I went to a horror movie, I wanted to be scared."

So with two album releases on Zappa's Straight label, Alice found himself being swooped up by Warner Brothers and all product released since then has been on the WB label.

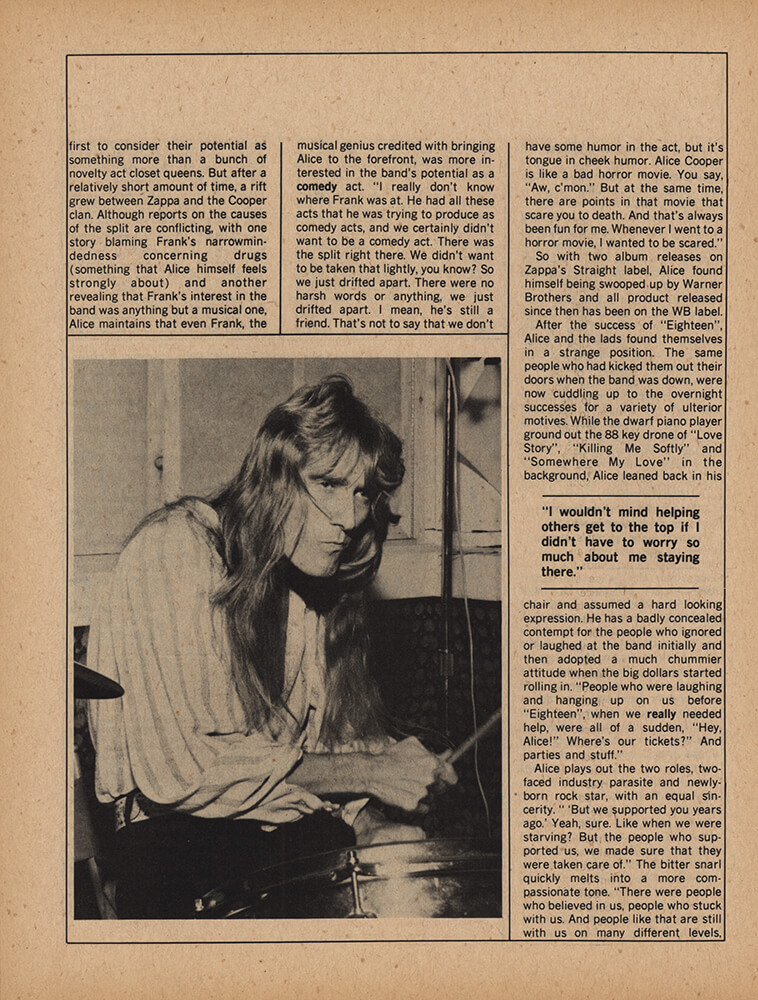

After the success of "Eighteen", Alice and the lads found themselves in a strange position. The same people who had kicked them out their doors when the band was down, were now cuddling up to the overnight successes for a variety of ulterior motives. While the dwarf piano player ground out the 88 key drone of "Love Story", "Killing Me Softly." and "Somewhere My Love" in the background, Alice leaned back in his chair and assumed a hard looking expression. He has a badly concealed contempt for the people who ignored or laughed at the band initially and then adopted a much chummier attitude when the big dollars started rolling in. "People who were laughing and hanging up on us before "Eighteen", when we really needed help, were all of a sudden, "Hey, Alice!" Where's our tickets?" And parties and stuff."

Alice plays out the two roles, two-faced industry parasite and newly-born rock star, with an equal sincerity. "'But we supported you years ago.' Yeah, sure. Like when we were starving? But the people who supported us, we made sure that they were taken care of." The bitter snarl quickly melts into a more compassionate tone. "There were people who believed in us, people who stuck with us. And people like that are still with' us on many different levels, people who used to work for record companies. People who used to throw a few jobs our way. A big gig was maybe working with Canned Heat for two hundred dollars, but at least they helped us out."

Being aware of the opposition a band can face from all corners of the industry, having experienced firsthand some of the less pleasant aspects of the often-backward industry, one would think Alice would be anxious to help out other aspiring acts, bands in much the same boat as the Cooper gang were once in. But the pressures of being Alice Cooper are apparently more time and energy consuming than many of us are willing to appreciate. "I wouldn't mind helping others get to the top so much, if I didn't have to worry so much about me staying there. It's easier to get there than it is to stay there in all reality. There are so many angles that you just have to keep pounding away at. It sounds real corny, but it's true."

Although Alice continually plays upon the same themes, essentially sex, violence and society's eventual retaliation, and although an aura of total decadence surrounds the entire Cooper concept, Alice staunchly maintains that decadence was only the theme for the band's last album, "Billion Dollar Babies". Alice Cooper was the spearhead of the now-accepted theatrical vanguard. As such, the band has opened up many different avenues of expression both musically and theatrically. One doubts, with good justification, that Bowie or the New York Dolls or the majority of the glitter-rockers would exist today if not for the early efforts of Alice Cooper. The effect that Alice Cooper has had on audiences internationally is remarkable, but the effect that they have had on other artists, who in turn have had a great influence on their audiences, is devastating. It is not unthinkable that Alice Cooper has totally altered the thinking of North America.

Alice is quick to point out that this year's feature on the band in Time magazine was a drastic departure from the norm for that publication. Time has never been overly concerned with rock performers, nor has it ever felt the need to do such an indepth study of any one artist. "That was the first time Time had used full colour, was for the piece on us." Alice puts perhaps a little too much emphasis on the last word of the sentence. He feels badly that the band is not really considered a band by all. Yet they are summarily excluded from all contact with the press. They tend to group together, avoiding contact with all the changing faces around them. They don't appear interested in the slightest in all the various games they could potentially play with the media. They leave that to Alice. Yet Alice firmly maintains that they are a band, with each individual member playing an important part "I get upset sometimes, not always, but when I read album reviews or sometimes even concert reviews, it's "Alice this" and "Alice that", but many people just don't seem to get the message that we're a band. We work out everything together. The music and the act aren't solely my creation, but the others don't always get the credit that they deserve and that's not right"

No one has quite been able to put their finger on the reason behind Alice's astounding popularity, but many have speculated on the possible effects an act like Alice's might have on an audience. Alice doesn't feel the act is in any way demoralizing their audiences. "It really all depends on the individual involved. Some people think we're a highly spiritual act, some think we're depraved. But the important thing is that the act makes people think. We don't want to come off being preachy, because I don't like being preached to. I don't like being told how to think and why. I just throw out an idea and say, "Here, take it." And you can take it anywhere you like. I don't really care. The only thing I promote is thinking. I don't care what they think, just so long as they do think something. I can't stand to see a dormant mind. It could get to the point where, like on the Outer Limits. "we have evolved into just brains." Or maybe energy or something, but right now we're all still down here, eating and getting drunk. We're not on that level yet. The only thing I'm saying is that so many people are just not thinking. They very rarely think about anything. They get locked into a pattern like robots. But when they come to see us, we give them a shock treatment so they have to think. We could take the act right now and turn it into a direct comedy act or we could take it and make it into Shakespeare. The reason we chose anti-heroics is because there aren't any good villains right now. And in order to have good theatre, you have to have a good villain. I'd rather see Bela Lugosi than the Lone Ranger and I'm sure any kid would too. But I don't think it has a demoralizing effect at all. Fifteen and sixteen year old kids are so much smarter now than they were when I was that age. They don't go, "Oooh, he did that so I'm gonna do it." They're really not like that any more. Kids have come up to me and said, "You know that C major 7th in the third chorus . . ." and I'm looking at the kid and he's already lost me. "The augmented diminished 13th that came in there gave it a sort of touch of..." and I'm going wait a minute! They all end up directing the theatre and the music like armchair quarterbacks... how would I have done it, type of thing. And that's the TV generation. They're so used to seeing it on TV."

So, regardless of all the implied perversities and sexual connotations involved in Alice's act, he strongly feels that, if anything, he is helping his audiences come to grips with some of their own pubescent fantasies. "When I was young, I had these thoughts which were considered dirty, but were in actual fact quite normal, only I didn't realize it. Today, kids realize it more and more and I hope it's partially due to the existence of bands like ours. I think we're helping people come to terms with their own inner thoughts by making fun of them. I guess Alice Cooper is like a good psychiatrist. Maybe someday they'll have a TV show, "Alice Cooper: Psychiatrist At Large". That would be neat."

Maybe, someday.