Article Database

Uncut

March 2021

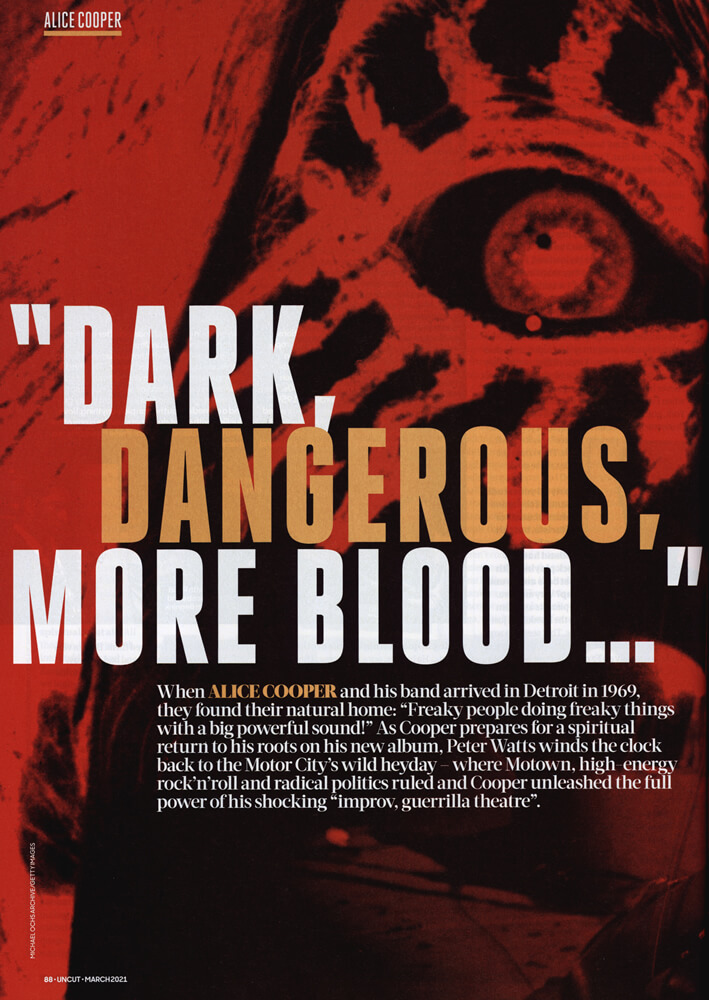

"Dark, Dangerous, More Blood..."

Author: Peter Watts

When ALICE COOPER and his band arrived in Detroit in 1969, they found their natural home: "Freaky people doing freaky things with a big power sound!" As Cooper prepares for a spiritual return to his roots on his new album, Peter Watts winds the clock back to the Motor City's wild heyday — where Motown, high-energy rock'n'roll and radical politics ruled and Cooper unleashed the full power of his shocking "improv, guerrilla theatre".

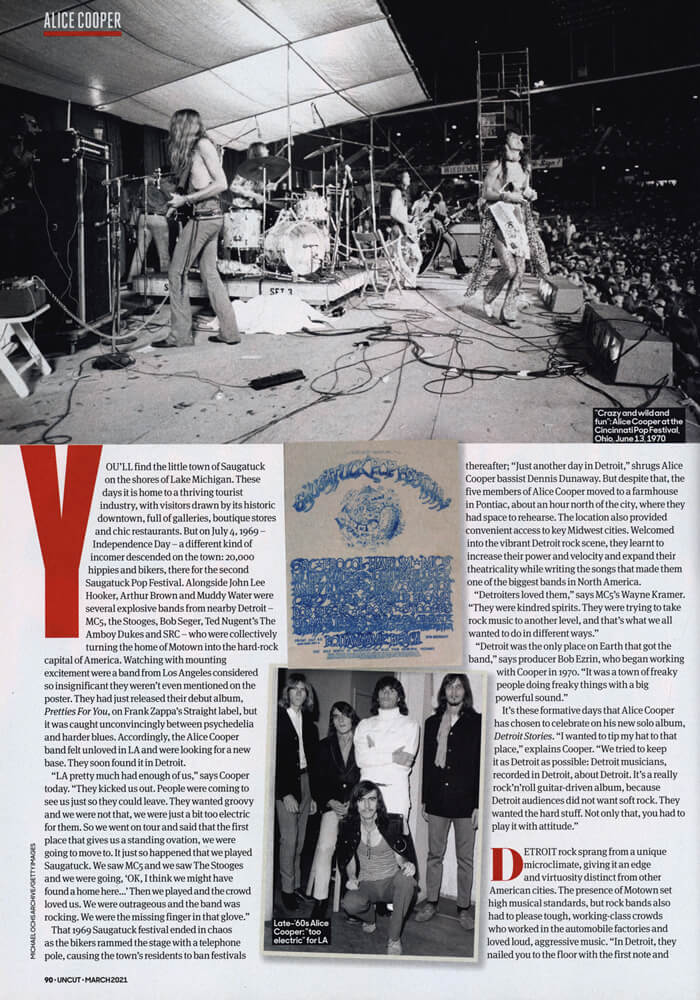

YOU'LL find the little town of Saugatuck on the shores of Lake Michigan. These days it is home to a thriving tourist industry, with visitors drawn by its historic downtown, full of galleries, boutique stores and chic restaurants. But on July 4, 1969 — Independence Day — a different kind of incomer descended on the town: 20,000 hippies and bikers, there for the second Saugatuck Pop Festival. Alongside John Lee Hooker, Arthur Brown and Muddy Water were several explosive bands from nearby Detroit — MC5, the Stooges, Bob Seger, Ted Nugent's The Amboy Dukes and SRC — who were collectively turning the home of Motown into the hard-rock capital of America. Watching with mounting excitement were a band from Los Angeles considered so insignificant they weren't even mentioned on the poster. They had just released their debut album, Pretties For You, on Frank Zappa's Straight label, but it was caught unconvincingly between psychedelia and harder blues. Accordingly, the Alice Cooper band felt unloved in LA and were looking for a new base. They soon found it in Detroit.

"LA pretty much had enough of us," says Cooper today. "They kicked us out. People were coming to see us just so they could leave. They wanted groovy and we were not that, we were just a bit too electric for them. So we went on tour and said that the first place that gives us a standing ovation, we were going to move to. It just so happened that we played Saugatuck. We saw MC5 and we saw The Stooges and we were going, 'OK, I think we might have found a home here...' Then we played and the crowd loved us. We were outrageous and the band was rocking. We were the missing finger in that glove."

That 1969 Saugatuck festival ended in chaos as the bikers rammed the stage with a telephone pole, causing the town's residents to ban festivals thereafter; "Just another day in Detroit," shrugs Alice Cooper bassist Dennis Dunaway. But despite that, the five members of Alice Cooper moved to a farmhouse in Pontiac, about an hour north of the city, where they had space to rehearse. The location also provided convenient access to key Midwest cities. Welcomed into the vibrant Detroit rock scene, they learnt to increase their power and velocity and expand their theatricality while writing the songs that made them one of the biggest bands in North America.

"Detroiters loved them," says MC5's Wayne Kramer. "They were kindred spirits. They were trying to take rock music to another level, and that's what we all wanted to do in different ways."

"Detroit was the only place on Earth that got the band," says producer Bob Ezrin, who began working with Cooper in 1970. "It was a town of freaky people doing freaky things with a big powerful sound."

It's these formative days that Alice Cooper has chosen to celebrate on his new solo album, Detroit Stories. "I wanted to tip my hat to that place," explains Cooper. "We tried to keep it as Detroit as possible: Detroit musicians, recorded in Detroit, about Detroit. It's a really rock'n'roll guitar-driven album, because Detroit audiences did not want soft rock. They wanted the hard stuff. Not only that, you had to play it with attitude."

DETROIT rock sprang from a unique microclimate, giving it an edge and virtuosity distinct from other American cities. The presence of Motown set high musical standards, but rock bands also had to please tough, working-class crowds who worked in the automobile factories and loved loud, aggressive music. "In Detroit, they nailed you to the floor with the first note and maintained that until the end," says Dennis Dunaway. "If you did a ballad, they ran you out of town."

"Detroit was a tough city with tough bands," continues Cooper drummer Neal Smith. "It put a harder image on Alice Cooper — the music, the image and everything."

This quality was born from something approaching resentment, or at least a suspicion that coverage of American music went from LA and New York, ignoring everything in between. "We thought we were getting short shrift," says Kramer. "It was like nothing cool could happen in Detroit. We made shock absorbers. We made mufflers. But we knew better. We were young and headstrong and we developed a pissy attitude that showed in the music. We worked extra hard, we sweated more, we played with more velocity, more passion, more commitment, and that filtered out to the other bands."

Detroit bands also learned from Motown and the city's black music scene. Racial tension seemed to dissipate when it came to music, with black and white artists playing the same venues and visiting the same music stores. Cooper says that as a longhaired hippie, he was welcome in any black club, while Smokey Robinson, The Supremes and The Temptations would come to their shows. Mitch Ryder's Detroit Wheels originally played R&B at black venues before moving into rock. They were widely respected as one of the tightest bands on the circuit, setting the standard for Detroit rock rhythm sections. "Mitch had all that soul in him and all the white acts would be watching the black artists and learning from them," says Detroit Wheels drummer Johnny Badanjek, who plays on Detroit Stories. "It absolutely influenced the playing. There was Benny Benjamin, Uriel Jones, Richard 'Pistol' Allen, those guys all had a beat. Those Motown players would do a session, then you'd see them in the bars doing a show. It was like the car line, they were just as productive."

WHEN Steve Hunter moved from rural Illinois to join Mitch Ryder's new band, Detroit, in 1970, he was originally living in the office of Creem magazine at Cass Avenue. Creem had been founded in 1969 by Barry Kramer, who also managed the Mitch Ryder group. Detroit would rehearse in the office, while the building hosted numerous after gig parties for the leading Detroit bands, cementing something that Hunter feels was unique to the city — a supportive scene.

"There wasn't a feeling of competition," says the guitarist who played with Lou Reed, on Alice Cooper solo albums and appears on Detroit Stories. "Bands really encouraged each other. We'd go and see Iggy or MC5 or Alice, and they'd see us. There was camaraderie among the bands and we rooted for each other. Creem was a national magazine but it had its finger on Detroit. It was the only magazine that got the Detroit scene, put it into a magazine and made sense of it. "

"That hard-rock scene was so vibrant, it was amazingly magical," agrees Bob Ezrin. "You could go to any club and see five or six amazing bands, all existing at the same time in a very small area, knowing each other and playing with each other. It was the centre of the rock universe."

Bands socialised at Alice Cooper's farmhouse in Pontiac or in Ann Arbor, where MC5 and The Stooges were based. Alice Cooper and the Stooges regularly played the Eastown Theatre, with MC5 across town at the Grande Ballroom. Detroit had enough venues and festivals to sustain dozens of bands. As well as MC5 and Stooges, there were The Frost, The Up and SRC plus several artists that would soon become huge — Bob Seger, Ted Nugent, Grand Funk Railroad and Suzi Quatro, then playing with Cradle. But the trinity of MC5, Stooges and Alice Cooper dominated.

"Playing with Iggy and MC5 was great for us," says Cooper. "We'd got so used to following Spirit or somebody like that. They were great musicians but didn't have that electricity and drama. The MC5 were just pure Detroit. They were a little bit R&B, they were hard rock, they were politically charged and they were all such good musicians. The Stooges were so hypnotic. They would just sit there and they never got in the way of Iggy's theatrics, who was as nasty as it got. I saw we could do something like that. Darker, dangerous, more blood, more force. The way that works is the band just attacks the audience, the band has to be merciless with the crowd. All those three bands — MCs, Stooges and Alice Cooper — worked so well together because we were three different types of theatre."

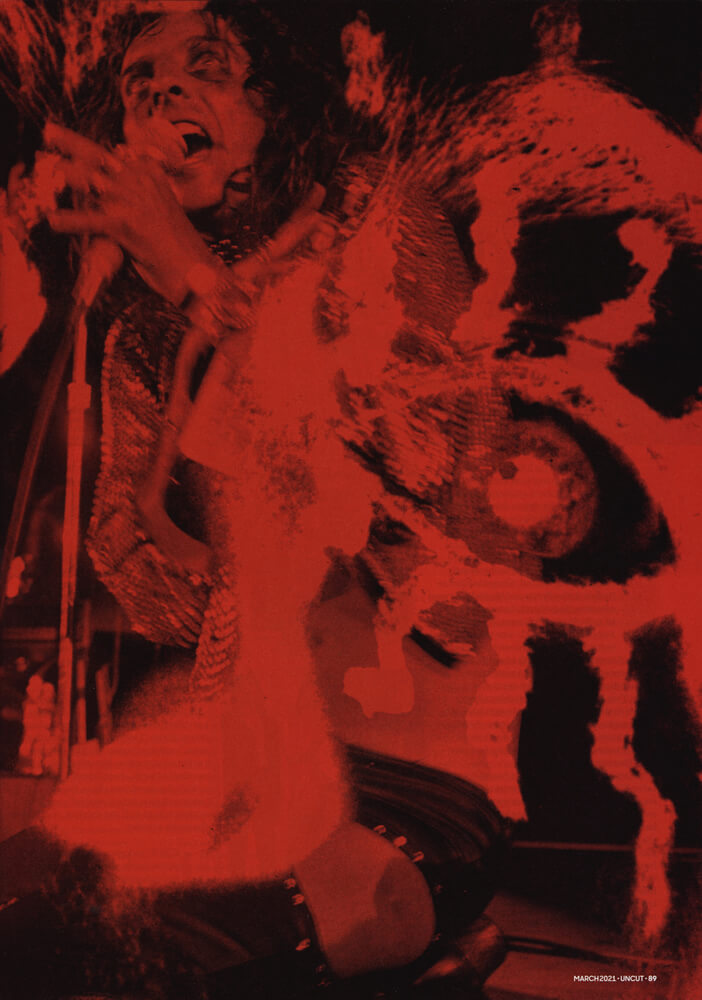

Alice Cooper's theatrics became legendary. The descent into the dark side began a few weeks after Saugatuck with the infamous incident at the Toronto Rock'n'Roll Revival, where a live chicken Cooper threw into the audience met a grisly end. Alice Cooper shows would later involve electric chairs, straitjackets and gallows. It was partly about survival, a way to keep up with the MC5 and Stooges. "The Detroit groups, I called them the Motor City Bad Boys, they let us into the circle," says Dunaway. "We were very different but they accepted us. Playing in Detroit, we realised we had to get more energy into our music, which we did, but how do you outpower those bands? You can't. So we decided to execute our singer."

In the early days in Detroit, the stage shows were more limited. "We couldn't afford TNT or gallows. so it was whatever we found," says Cooper. "It was improv, guerrilla theatre. One night, I found a mop. That mop could go be a girl, it could be something to swing around, it could be a weapon, it could be something I ride on, it could go be a crutch, it could be a guitar. But the feather pillow was always a good one."

The feather pillow became Alice Cooper's trademark. At the finale, Cooper would tear it open and guitarist Michael Bruce would spray it with a CO2 canister, covering the audience in feathers like an indoor snowstorm. "We played a lot of shows together and I saw the theatrical side of their band really emerge and blossom," says Kramer. "They were trying to create as much theatrically dramatic chaos as they could. It wasn't really dangerous. It didn't scare you. It was crazy and wild and fun, but it wasn't Iggy. He was really scary, dancing like a dervish, possessed. You never got the sense with Iggy it was for show. It was a way of life."

One aspect of the Detroit scene that Alice Cooper avoided was politics. Detroit was an important city for organised labour, while the civil rights era brought riots in 1967, the aggression of the political movements seeming to mirror the energy of the rock. "There was a political underbelly in Detroit," says Mitch Ryder guitarist Steve Hunter. "It was those same political undercurrents you'd find in Berkeley or New York. Younger people who were fed up with the way thing were, and that sparked a lot of music. The MC5 really embraced that."

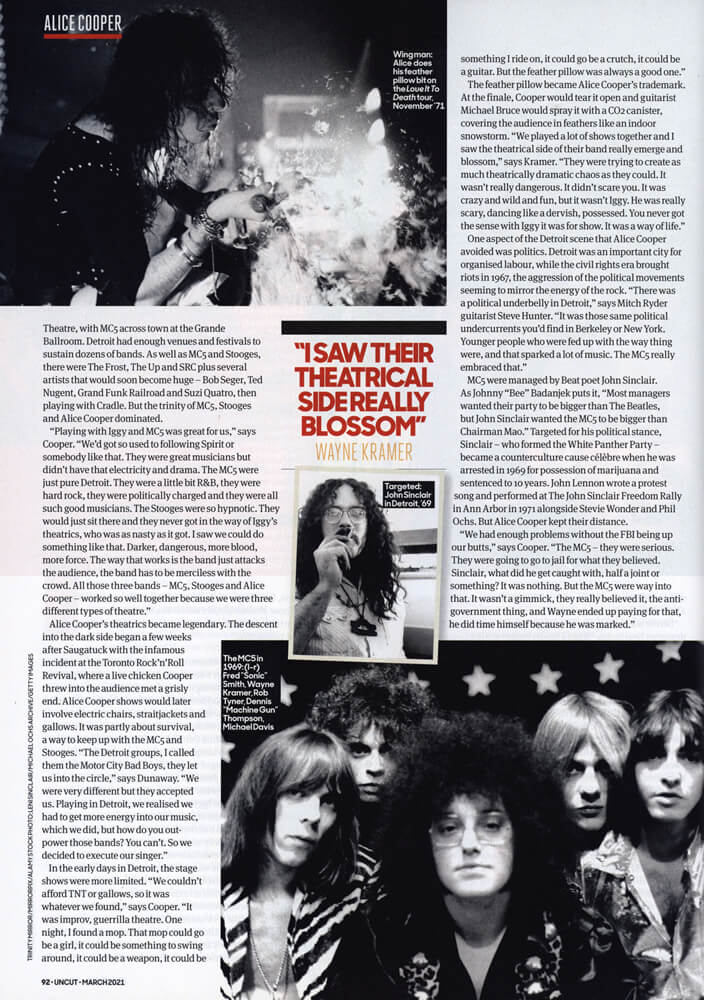

MC5 were managed by Beat poet John Sinclair. As Johnny "Bee" Badanjek puts it, "Most managers wanted their party to be bigger than The Beatles, but John Sinclair wanted the MC5 to be bigger than Chairman Mao." Targeted for his political stance, Sinclair — who formed the White Panther Party — became a counterculture cause celebre when he was arrested in 1969 for possession of marijuana and sentenced to 10 years. John Lennon wrote a protest song and performed at The John Sinclair Freedom Rally in Ann Arbor in 1971 alongside Stevie Wonder and Phil Ochs. But Alice Cooper kept their distance.

"We had enough problems without the FBI being up our butts," says Cooper. "The MC5 — they were serious. They were going to go to jail for what they believed. Sinclair, what did he get caught with, half a joint or something? It was nothing. But the MC5 were way into that. It wasn't a gimmick, they really believed it, the antigovernment thing, and Wayne ended up paying for that, he did time himself because he was marked."

While MC5 and Stooges wanted to build their audience, neither band matched the ambition of Alice Cooper. Six months after arriving in Detroit, in March 1970, the group released their second LP on Frank Zappa's Straight label. Easy Action was produced by future Neil Young producer David Briggs, but he didn't get the band and it showed. Easy Action tanked. Sick of failure, the band put their heads together.

"We didn't get into rock'n'roll to be poor," says Smith. "We wanted a No 1 album. So we looked at the producers to see who had the most hits and saw it was The Guess Who. We went after their producer, Jack Richardson, in Toronto, and he sent his assistant Bob Ezrin to watch us. We were lucky to get a third chance after two flops but we were dedicated to make it work and to get out of the Midwest. We were from the southwest, we were used to sunshine. In Detroit, it snowed every day."

Ezrin saw Alice Cooper at Max's Kansas City in New York in September. He was supposed to tell them politely that his boss wasn't interested but instead struck a deal. That's how he found himself at the farmhouse in Pontiac later in 1970. Zappa had sold Straight Records to Warner Bros, and the label was reluctantly funding a session in Chicago. If this was to go anywhere, Ezrin had to knock the band into shape and find a hit. "We went to the barn and started on 'Is It My Body'," says Ezrin. "I listened, worked out what they were trying to do and then came up with ways to help them do it more effectively. We stripped the song back and rebuilt it with discipline and focus, making the rhythm guitar a central focus of the band. We counted it off and it was a different song and it was powerful and we all knew it. Then we moved on to 'I'm Eighteen' and did the same thing. At the end of that first weekend we had knocked together the arrangements on a couple of songs and fallen in love with each other. We established a working relationship that basically survives to this day."

The band soaked it up like sponges, learning to mix tight rockers with longer tracks like "Black Juju" that could sustain the frontman's theatrics. "I'm Eighteen" was released as a single in November 1970 and found a fan in Rosalie Trombley at CKLW. The radio station broadcast from Canada into the US, hitting not just Detroit but also Ohio, Pennsylvania, Indiana and Illinois. "I once asked Rosalie what appealed to her about 'I'm Eighteen'," says Dunaway. "She said it was the lyrics. Before the first verse was over she knew it was a hit. The other DJs told her she had to stop playing this song by the band that threw a chicken in the audience, but every phone was ringing off the hook with requests."

The success of "I'm Eighteen" paved the way for two 1971 albums, Love It To Death and Killer, which transformed Alice Cooper from local heroes into international celebrities. "'I'm Eighteen' got picked up by the biggest station in the Midwest, that was the launching point," says Cooper. "That never would have happened in LA or New York. 'Eighteen' was one of those songs that had to come out of the Midwest. After that, we became a whole other thing."

WHEN Cooper and Ezrin got together in 2019 to discuss a new project, they found they were both wistful for those formative Detroit years. Together they hatched a plot to record an album about the city, using Detroit musicians from the era. They called it Detroit Stories and called in Wayne Kramer, who began to co-write. They even discussed bringing in guest vocalists like Iggy Pop but decided that would detract from the fact this was, after all, an Alice Cooper record.

Cooper was inspired by stories and characters he had known in Detroit. "Some are real, some are archetypes, but we wanted to either tell their story or tell a story using their voice and it all had to relate to Detroit," says Ezrin. Musically, they wanted to capture the hard edge of Detroit rock but without losing the R&B flavour. That came from drummer Johnny Badanjek and younger local bassist Paul Rudolph. Guitarist Steve Hunter of Mitch Ryder's Detroit also played on a couple of songs, including a cover of Lou Reed's "Rock N Roll", which he recorded with Detroit back in 1971. Mark Farner of Detroit's Grand Funk Railroad contributed to covers of songs by Bob Seger and the MC5, which fit snugly alongside originals such as "Detroit City 2021", "Drunk And In Love" and "$1000 High Heel Shoes" — all recorded in the Detroit suburb of Royal Oak.

Although a few non-Detroit musicians played on the record — including Joe Bonamassa and Larry Mullen Jr — Cooper recorded two songs with the surviving members of the Alice Cooper band — Neal Smith, Dennis Dunaway and Michael Bruce. It seemed only right that the four original members, who remain close friends, got the opportunity to revisit those Detroit days. "It started in Arizona, went to California, but in Detroit, that's where it bloomed," says Neal Smith. "That's when it became Alice Cooper for real."

"People came out of curiosity and then they liked it and told their friends about it and pretty soon we were headlining," says Cooper. "That whole area just really loved hard rock, so we could play every weekend and it was enough to keep the band going. We were building that audience and word of mouth got out. In Detroit, we finally found a place that appreciated what we were doing."

Detroit Stories is released by earMUSIC on February 26.

"We Learned Fast!"

Cooper and co on their breakout hit, "I'm Eighteen"

ALICE Cooper's breakout single had been part of their set for some months before Bob Ezrin visited them in Pontiac to work on pre-production. At that time it was a longer and more complex song, but Ezrin could hear it had potential as a hit.

"Bob said let's do that song of your, 'I'm Edgy'," recalls Dennis Dunaway. "We said, 'Bob, it's called "I"m Eighteen"'. At the time is was this sprawling song with a moody bluesy organ intro by Michael Bruce that built up until the song hit."

Ezrin told them to cut the intro completely and get straight to the meat of the song. "It was what we needed," says Dunaway. "The old 'I'm Eighteen' would have done well on FM, but we wanted an AM hit. It had to be three minutes. We were likes sponges for anything musical — if something needed doing that made our music better, we did it and we learned fast."

"'Eighteen' didn't sound like any other band and was really kind of punk sounding," says Cooper. "And that whole idea — 'I'm eighteen and I like it' — was very subversive in its message.".