Article Database

Record Collector

June 1999

The Life and Crimes of Alice Cooper

A new 4-CD anthology seeks to establish the shock rockers credentials.

Author: Mark Paytress

1972 was a vintage year for summer anthems: Mott The Hoople's "All The Young Dudes", Derek and the Dominos' "Layla", Hawkwind's "Silver Machine", even Gary Glitter's "Rock 'n' Roll Part 2". Each confirmed that rumours of pop's demise after the Beatles break-up had been premature. But one record -out-flanked them all - Alice Cooper's "School's Out". A revved-up Harley-Davidson chug-a-lug, with a machete-sharp riff that ate the Stones' "Jumpin' Jack Flash" for breakfast, "School's Out" prompted moral guardians to reach for their panic buttons once more.

The authority-snubbing lyric was bad enough, but what worried them most was Cooper's persona. His ragged clothes, bedraggled hair and ghoulishly painted face made him appear like a pantomime Charles Manson. His act, reputed to including biting the heads off chickens (untrue), mock executions and games with the band's pet boa constrictor, even prompted the Who's Pete Townshend to quip: "He's sick, tragic, pathetic". Cooper claimed, with some justification, to be merely a reflection of the world around him.

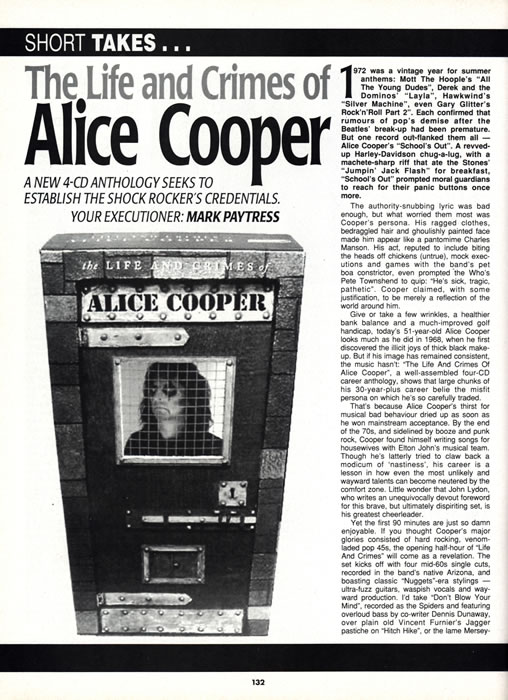

Give or take a few wrinkles, a healthier bank balance and a much-improved golf handicap, today's 51-year-old Alice Cooper looks much like he did in 1968, when he first discovered the illicit joys of thick black makeup. But if his image has remained consistent, his music hasn't: "The Life And Crimes of lice Cooper", a well-assembled four-CD career anthology, shows that large chunks of his 30-year-plus career belie the misfit persona on which he's so carefully traded.

That's because Alice Cooper's thirst for musical bad behaviour dried up as soon as as he won mainstream acceptance. By the end of the 70s, and sidelined by booze and punk rock, Cooper found himself writing songs for housewives with Elton John's musical team. Though he latterly tried to claw back a modicum of 'nastiness', his career is a lesson in how even the most unlikely and wayward talents can become neutered by the comfort zone. Little wonder that John Lydon, who write an unequivocally devout foreword for his brave, but ultimately dispiriting set, is his greatest cheerleader.

Yet the first 90 minutes are just so damn enjoyable. If you thought Cooper's major glories consisted of hard rocking, venom-laded pop 45s, the opening half of "Life and Crimes" will come as a revelation. The set kicks off with four mid-60s single cuts, recorded in the band's native Arizona, and boasting classic "nugget"-era stylings - ultra-fuzz guitars, waspish vocals and wayward production. I'd take "Don't Blow Your Mind", recorded as the Spiders and featuring overloud bass by co-writer Dennis Dunaway, over the plain old Vincent Furnier's Jagger pastiche on "Hitch Hike", or the lame Mersey-fake "Why Don't You Love Me". But "Lay Down and Die, Goodbye", the last of the Arizona cuts and recorded as the Nazz (not to be confused with Todd Rundren's combo), basks in a Yardbirds-like Gothic melancholy, providing a hint of things to come.

After moving to California, where they quickly became known as "the most hated group in L.A.", the boys from Phoenix developed a new sensibility, giving their predilection for darkness a comic twist. Calling themselves Alice Cooper (the letters were spelled out on a Ouija board, so the story goes), the quintet of hairy mid-west misfits confounded audiences who'd expected to see a folksy hippie chick on stage. Worse still, at a time when psychedelic improvisation and sunshine anthems were all the rage, Alice Cooper's witty, deconstructed songs that would stop unexpectedly, or break into unlikely waltz rhythms, sounded incompetent and plain silly.

Most Talked-About

Surely, it's this reaction which helped propel the runt of the Hollywood litter to become the most talked-about act of 1972. (Much the same as Bolan, Bowie and Elton wreaked revenge on their late 60s detractors in the UK) Many have dismissed Alice Cooper's late 60s work as merely a springboard towards greater things, but the handful of cuts here, including the classic outsider anthem, "Nobody Likes Me" (here in early demo form), and "Levity Ball" (which borrows heavily from the Floyd's "Astonomy Domine"), stand as the band's most original and misunderstood work.

The blossoming of Alice Cooper into rock 'n' roll's foremost statesman of outrage may have been fuelled by retribution, but it took a relocation to the tougher climes of Detroit, the arrival of Bob Ezrin and some inaccurate press reports concerning chicken abuse at the end of the decade to encourage Warner Brothers to wrest the band from Frank Zappa's Straight label and capitalise on its idiot bastard sons. Out went the tricky time signatures and kitsch/camp stage act. Instead, Alice Cooper devised a hard-bitten theatrical show that transformed its frontman into the ultimate rock anti-hero - with suitably digestible, melodramatic hard rock songs to match.

He influence of Ezrin who worked on the band's third album, 1971's "Love It To Death", was crucial. "The beginning of the Alice Cooper radio sound" is how Alice describes that albums "Caught In A Dream", though it was another single, "I'm Eighteen", that caught the attention. Tight, edgy, snotty, anthemic, it provided a model for Cooper's future work - though it was rarely surpassed. Up there, too, is "Ballad of Dwight Fry", a stage favourite that shares many similarities with Bowie's work from the period - not least the song's preoccupation with madness.

By the time "Killer" was released in late 1971, Alice Cooper was on a roll. The rock 'n' rolling "Under My Wheels", complete with honking sax, sounded like a brattish response to "Brown Sugar"; "Be My Lover" proved it wasn't only Bowie who was pinching riffs from the Velvets' "Sweet Jane"' while "Desperado" sought to unite the Doors with Roger Daltrey. Most compelling were two more obviously theatrically-conceived numbers, "Dead Babies", and the sleazy title track, both of which pleasingly took old-style diversions midway through the song.

On the cusp of major breakthrough, Alice Cooper never sounded this good again, with the exception of the "School's Out" 45. The similarly-titled album was a major disappointment, which is why the West Side Story inspired "Gutter Cats Vs. The Jets" is the only other inclusion here. A prog-like grandeur set in with "Hello Hurray" (Bono's first single purchase, unsurprisingly), although I've always been a sucker for the title track of 1973's "Billion Dollar Babies", with its dead-drop drum patterns and decadence-drenched voices (and, hey, there's Mr. Nice Guy Donovan on b/v's!).

After the Alice Cooper band fell apart during the making of "Muscle of Love", released at the end of 1973, Alice surrounded himself with session players and attempted a career shift similar to that undertaken by Rob Stewart around the same time. He unwittingly wrote a feminist anthem, "Only Women Bleed", sang treacly, Radio 2-style ballads like 1976's "I Never Cry", and watches his fan base desert him in droves. The inclusion of "I Miss You", from the old Cooper band's 1977 "Battle Axe" album (credited to the Billion Dollar Babies), serves to remind us just how far Alice had strayed from his patch.

If anyone can get through Discs Three and Four without resorting to anti-depressants, they're made of a tougher stuff than I. For the rest of the set limps along in its polished, AOR rock way, very American, very 80s, very Rock Is Dead, Let's Make Money. One track, 1981's "Who Do You Think We Are?", is mildly interesting only in that it reveals that Alice was digesting copies of survivalist magazine Soldier Of Fortune when he wasn't playing golf with ex-Presidents.

The past decade has seen Cooper carousing with the likes of Guns N' Roses, Soundgarden's Chris Cornell, Aerosmith's Steve Tyler, Rob Zombie and Zodiac Mindwarp - collaborations that suggest hipness-by-association rather than epochal meetings of great muscial minds. He's now writing songs about the adverse influence of the internet on young people. Alice Cooper is probably more frightening and dangerous than he ever was. Guilty, m'lud.