Article Database

Guardian

June 13, 2014

'We Upset the Whole World'

Revelling in death and youthful angst, Alice Cooper was the early 70s' greatest pop villain. As a new documentary on his life and work opens, the shock-rock pioneer speaks to Simon Reynolds.

Author: Simon Reynolds

Alice Cooper is reminiscing about the days when he killed himself for a living. "Any time you have moving parts on stage, you are asking for Spinal Tap," he says of the gallows and the guillotine that were climactic fixtures of his live shows in the early 1970s. "And when it doesn't work, you have to play it for comedy."

But the time in England when the gallows broke was no laughing matter. "There was a wire connected to my back, it stopped the noose from hitting my neck — we'd done the trick 100 times, never thinking: 'Maybe that wire is getting brittle.' Then it snapped and the noose grabbed me for real." Cooper was quick-witted enough to tilt his chin up and slip through the noose. He was lucky to escape with a nasty rope burn to his throat.

Now, 41 years after that close shave, Cooper sits in a downtown Los Angeles hotel suite. Directly opposite is the Grammy Museum, where the previous night Super Duper Alice Cooper, a documentary film about his life, made its West Coast debut. Among the invitation-only audience were the legendary groupie Pamela Des Barres (a friend of the band, who were collectively called Alice Cooper before the singer, previously known as Vincent Furnier, went solo and adopted the name for himself) and sundry Cooper-influenced metal performers such as Twisted Sister singer Dee Snider.

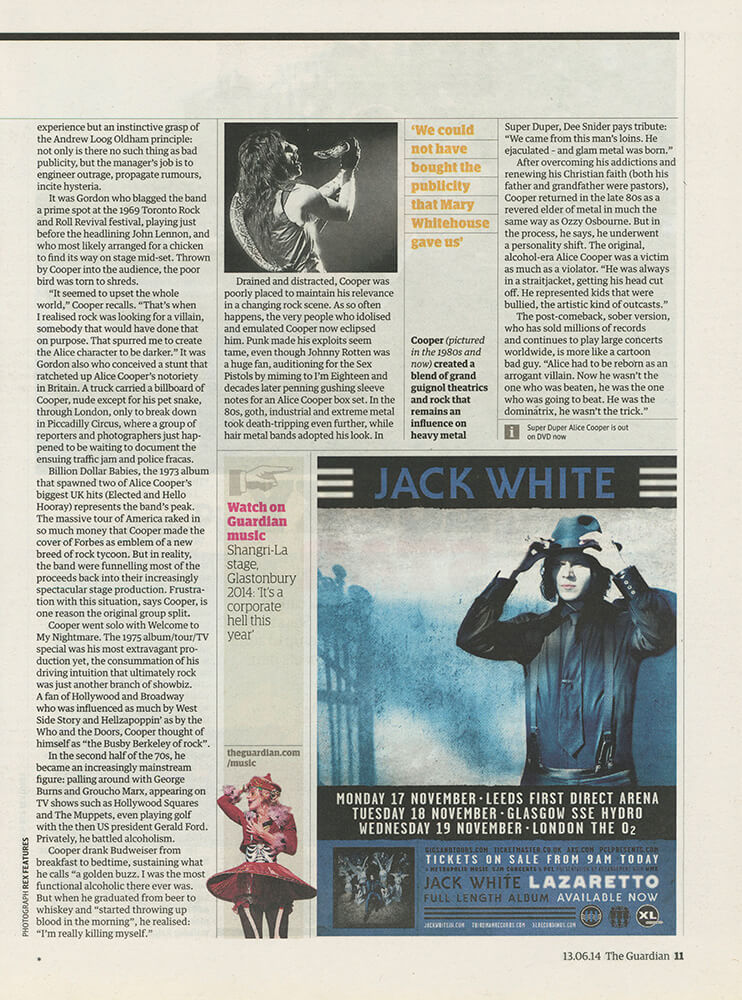

Wearing white jeans with an excess of zips, a black T-shirt, and a sepulchral medallion nestled in a thicket of chest hair, Cooper looks much the same at 66 as he did in his 70s heyday, give or take a few wrinkles and some paunch. But then when you watch the archive footage spliced into Super Duper, it is striking that he never really seemed like a young man. From his swarthy, crow-like countenance to his scrawny body, Cooper was never going to become a rock star through sexual magnetism, nor through the strength and beauty of his voice.

Instead he became one of the best "bad" singers rock'n'roll has ever known, his haggard rasp equally suited to the proto-grunge snarl of I'm Eighteen (his breakthrough US hit) and the megalomaniacal bombast of Elected. Abandoning "erotic politics" as a faded relic of the idealistic 1960s, Cooper based his act around death, releasing albums including Killer and Love It to Death, and tracks such as the necrophilia anthem I Love the Dead. The band's hard-riffing tunes and Grand Guignol theatrics drew a vast following of "sick things": young kids looking for a nihilistic new sensibility that was as repellent to older rock fans as it was to their parents' generation.

For a while Cooper was even bigger in Britain than he was in the US. His infamy was boosted by a campaign to ban his concerts led by the Labour MP Leo Abse and by Mary Whitehouse's efforts to stop the BBC airing the group's No 1 single School's Out. "Boy, we could not have bought that publicity," Cooper laughs. "They couldn't figure out why we were sending him cigars and her flowers. But every time they spent an extra hour trying to ban us in England, they helped us so much."

Abse and Whitehouse formed an unlikely alliance, given that the Pontypool MP had been an architect of the permissive society by pushing for the decriminalisation of homosexuality. But at a time of anxiety about rising levels of youth crime, Alice Cooper's disturbing imagery and gory theatrics were easily connected in the popular imagination with A Clockwork Orange and the copycat ultraviolence that Stanley Kubrick's movie had allegedly inspired.

"When I saw the film, I thought, there's an awful lot of Alice in Alex," Cooper says of Malcolm McDowell's delinquent anti-hero. "Like me, he's got a snake, he's wearing eye make-up. And later McDowell actually told me: 'There's a few Alice references in there.' So I totally related to A Clockwork Orange — not the mindless violence, but the fact that violence has its place in theatrics."

British rock always was more theatrical than its US counterpart. Often this involved destruction or macabre gimmickry: the Move smashing TV sets, Arthur Brown and his flaming helmet, Screamin' Lord Sutch making an entrance from inside a coffin. "That's why most people thought we were British at first," Cooper says.

Another thing in common with UK rock was the band's art-school genesis. "Me and Dennis Dunaway, our bassist, were both art majors and probably the two strongest forces as far as the image and the staging," says Cooper. "We were Salvador Dali fans."

As Super Duper Alice Cooper, the group started out in Phoenix, Arizona as a high-school Beatles parody act called the Earwigs, before evolving into the more serious punkadelic garage band the Spiders. By 1969, they had moved to LA and hooked up with manager Shep Gordon, a young man with no music industry experience but an instinctive grasp of the Andrew Loog Oldham principle: not only is there no such thing as bad publicity, but the manager's job is to engineer outrage, propagate rumours, incite hysteria.

It was Gordon who blagged the band a prime spot at the 1969 Toronto Rock and Roll Revival festival, playing just before the headlining John Lennon, and who most likely arranged for a chicken to find its way on stage mid-set. Thrown by Cooper into the audience, the poor bird was torn to shreds.

"It seemed to upset the whole world," Cooper recalls. "That's when I realised rock was looking for a villain, somebody that would have done that on purpose. That spurred me to create the Alice character to be darker." It was Gordon also who conceived a stunt that ratcheted up Alice Cooper's notoriety in Britain. A truck carried a billboard of Cooper, nude except for his pet snake, through London, only to break down in Piccadilly Circus, where a group of reporters and photographers just happened to be waiting to document the ensuing traffic jam and police fracas.

Billion Dollar Babies, the 1973 album that spawned two of Alice Cooper's biggest UK hits (Elected and Hello Hooray) represents the band's peak. The massive tour of America raked in so much money that Cooper made the cover of Forbes as emblem of a new breed of rock tycoon. But in reality, the band were funnelling most of the proceeds back into their increasingly spectacular stage production. Frustration with this situation, says Cooper, is one reason the original group split.

Cooper went solo with Welcome to My Nightmare. The 1975 album/tour/TV special was his most extravagant production yet, the consummation of his driving intuition that ultimately rock was just another branch of showbiz. A fan of Hollywood and Broadway who was influenced as much by West Side Story and Hellzapoppin' as by the Who and the Doors, Cooper thought of himself as "the Busby Berkeley of rock".

In the second half of the 70s, he became an increasingly mainstream figure: palling around with George Burns and Groucho Marx, appearing on TV shows such as Hollywood Squares and The Muppets, even playing golf with the then US president Gerald Ford. Privately, he battled alcoholism.

Cooper drank Budweiser from breakfast to bedtime, sustaining what he calls "a golden buzz. I was the most functional alcoholic there ever was. But when he graduated from beer to whiskey and "started throwing up blood in the morning", he realised: "I'm really killing myself."

Drained and distracted, Cooper was poorly placed to maintain his relevance in a changing rock scene. As so often happens, the very people who idolised and emulated Cooper now eclipsed him. Punk made his exploits seem tame, even though Johnny Rotten was a huge fan, auditioning for the Sex Pistols by miming to I'm Eighteen and decades later penning gushing sleeve notes for an Alice Cooper box set. In the 80s, goth, industrial and extreme metal took death-tripping even further, while hair metal bands adopted his look. In Super Duper, Dee Snider pays tribute: "We came from this man's loins. He ejaculated — and glam metal was born."

After overcoming his addictions and renewing his Christian faith (both his father and grandfather were pastors), Cooper returned in the late 80s as a revered elder of metal in much the same way as Ozzy Osbourne. But in the process, he says, he underwent a personality shift. The original, alcohol-era Alice Cooper was a victim as much as a violator. "He was always in a straitjacket, getting his head cut off. He represented kids that were bullied, the artistic kind of outcasts."

The post-comeback, sober version, who has sold millions of records and continues to play large concerts worldwide, is more like a cartoon bad guy. "Alice had to be reborn as an arrogant villain. Now he wasn't the one who was beaten, he was the one who was going to beat. He was the dominatrix, he wasn't the trick."

Super Duper Alice Cooper is out on DVD now.