Article Database

Esquire

April 1985

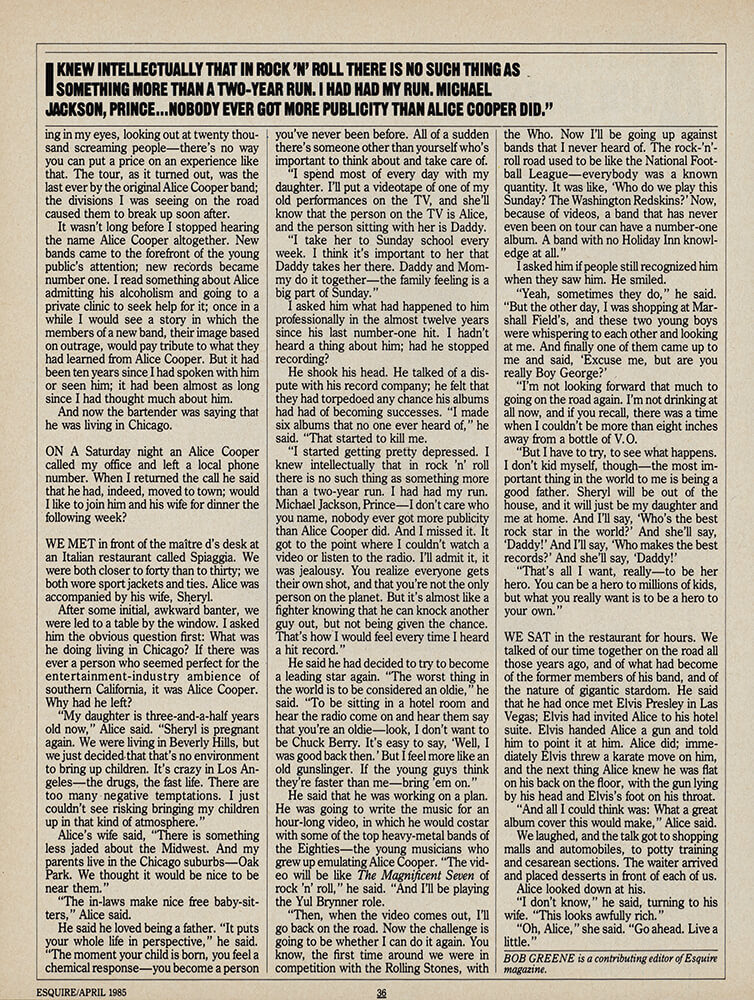

Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore

He's left the glitter of L.A. to be a middle-American dad

Author: Bob Greene

There is a delicatessen near where I work; it has a service bar in the back, and sometimes at the end of the day I will stop in there.

One night I did. The bartender said, "A friend of yours was in the restaurant the other day."

"Oh?" I said. "Who's that?"

"Alice Cooper," the bartender said.

That seemed odd. "Are you sure?" I said.

"It was him all right," the bartender said. "He had his wife and daughter with him."

"What do you suppose he was doing in Chicago?" I said.

"Somebody asked him that, " the bartender said. "He said that he was living here now."

"Alice Cooper is living in Chicago?" I said.

"That's what he said, " the bartender said. "I'm right about him being a friend of yours, arent I?"

Yes, he was right. For a brief period of time - not that long, no more than a month, really - I suppose you could even have said that we were best friends.

In 1973, in and effort to take a look at the world of rock 'n' roll from the inside, I made arrangements to join a band I became as a performing member. The band I became a part of was Alice Cooper, named after its lead singer, a former high school athlete from Arizona who had changed his name from Vincent Furnier and subsequently became one of the biggest pop stars in the world.

The Seventies were a time when planned outrage was in fashion, and Alice Cooper was taking full advantage of it. He was a forerunner of todays fascination with violence, harsh sexuality, and androgyny; his stage show featured simulated bloodletting, raw, suggestive song lyrics, and leering incitements of his young audiences. Alice appeared onstage every night wearing grotesque facial makeup and outlandish costumes; his show was the epitome of calculated tastelessness.

It was working to perfection. The year I joined up the band took in more than $17 million; they played before more than eight hundred thousand customers in live performance. There wasn't a week that Alice's name failed to appear in one national publication or another. In Britain a member of Parliament, Leo Abse, attempted to have the Alice Cooper show banned. He based his position on what his teenage children had told him about Alice. "They tell me Alice is absolutely sick," he said, "and I agree with them.I regard his act as an incitement to infanticide for his sub-teenage audience. He is deliberately trying to involve these kids in sadomasochism. He is peddling the culture of the concentration camp. Pop is one thing; anthems of necrophilia are another."

I joined the band and sang background vocals on one of their albums; I went on a nationwide tour with them and played a role on their violent stage show every night. My purpose was to try to see the rock 'n' roll road from their vantage point-from the stage, from the limousines, from the chartered jets-and to write a book about it.

I can't exactly say that Leo Abse's summation of the Alice Cooper show was wrong; actually, it was a fairly accurate appraisal. But I found something out about Alice; he was one of the brightest, funniest people I had ever met. He realized what the tone of the decade was; he was selling his young audiences what they were eager to buy, but he was full of a sense of irony about it. He was as appalled by their avid acceptance of his shows bloodlust as was the most conservative fundamentalist minister; the difference was, even though he was appalled, he was becoming very wealthy from it.

On the tour I joined, his original band was in the process of falling apart. There were rampant jealousies among the members; they resented the individual fame that Alice was attaining; Alice was becoming uneasy about having to go onstage and be Alice every night; he seemed to sense that he had created a monster, and that he was that monster. He was drinking heavily and staying barricaded in his hotel rooms between performances.

He wasn't speaking much with his fellow band members, and he wasn't going out, so he and I became unlikely friends. He was twenty-five; I was twenty-six. We would spend hours every day and night just sitting in his room talking and drinking and watching television while bodyguards kept fans away. We came to genuinely like each other, and our companionship grew to be a welcome one. It was destined not to continue; when the tour ended he went to live in California, and I went back to my home in Chicago. But we had each found someone of whom we were genuinely fond.

I have to say, that tour was one of the most interesting things that ever has happened to me. Standing onstage every night, the Super Trouper spotlights glaring in my eyes, looking out at twenty thousand screaming people - there's no way you can put a price on an experience like that. The tour, as it turned out, was the last ever by the original Alice Cooper band; the divisions I was seeing on the road caused them to break up soon after.

It wasn't long before I stopped hearing the name Alice Cooper altogether. New bands came to the forefront of the young publics attention; new records became number one. I read something about Alice admitting his alcoholism and going to a private clinic to seek help for it; once in a while I would see a story in which the members of a new band, their image based on outrage, would pay tribute to what they had learned from Alice Cooper. But it had been ten years since I had spoken with him or seen him; it had been almost as long since I had thought much about him.

And now the bartender was saying that he was living in Chicago.

On a Saturday night an Alice Cooper called my office and left a local phone number. When I returned the call he said that he had, indeed, moved to town; would I like to join him and his wife for dinner the following week?

We met in front of the maitre d's desk at an Italian restaurant called Spiaggia. We were both closer to forty than to thirty; we both wore sports jackets and ties. Alice was accompanied by his wife, Sheryl.

After some initial awkward banter, we were led to a table by the window. I asked him the obvious question first; What was he doing living in Chicago? If there was ever a person who seemed perfect for the entertainment-industry it was Alice Cooper. Why had he left?

"My daughter is three-and-a-half years old now," Alice said. "Sheryl is pregnant again. We were living in Beverly Hills, but we just decided that is no environment to bring up children. It's crazy in Los Angeles - the drugs, the fast life. There are too many negative temptations. I just couldn't see risking bringing my children up in that kind of atmosphere."

Alices wife said, "There is something less jaded about the Midwest. And my parents live in the Chicago suburbs - Oak Park. We thought it would be nice to be near them."

"The in-laws make nice free baby-sitters," Alice said.

He said he loved being a father. "It puts your whole life in perspective," he said. "The moment your child is born, you feel a chemical response - you become a person you've never been before. All of a sudden there's someone other than yourself who's important to think about and take care of.

"I spend most of every day with my daughter. I'll put a videotape of one of my old performances on the TV, and she'll know that the person on the TV is Alice, and the person sitting with her is Daddy.

"I take her to Sunday school every week. I think it's important to her that Daddy takes her there. Daddy and Mommy do it together - the family feeling is a big part of Sunday."

I asked him what had happened to him professionally in the almost twelve years since his last number-one hit. I hadn't heard a thing about him; had he stopped recording?

He shook his head. He talked of a dispute with his record company; he felt that they had torpedoed any chance his albums had had of becoming successes. "I made six albums that no one ever heard of," he said. "That started to kill me."

"I started getting pretty depressed. I knew intellectually that in rock 'n' roll there is no such thing as something more than a two-year run. I had had my run. Michael Jackson, Prince - I don't care who you name, nobody ever got more publicity than Alice Cooper did. And I missed it. It got to the point where I couldn't watch a video or listen to the radio. I'll admit it, it was jealousy. You realize everyone gets their own shot, and that your not the only person on the planet. But it's almost like a fighter knowing that he can knock another guy out, but not being given the chance. That's how I would feel every time I heard a hit record."

He said he had decided to try to become a leading star again. "The worst thing in the world is to be considered an oldie," he said. "To be sitting in a hotel room and hear the radio come on and hear them say you're and oldie - look, I don't want to be Chuck Berry. Its easy to say, 'Well, I was good back then.' But I feel more like an old gunslinger. If the young guys think they're faster than me - bring 'em on."

He said that he was working on a plan. He was going to write the music for an hour-long video, in which he would costar with some of the top heavy-metal bands of the Eighties - the young musicians who grew up emulating Alice Cooper. "The video will be like The Magnificent Seven of rock 'n' roll," he said. "And I'll be playing the Yul Brynner role.

"Then, when the video comes out, I'll go back on the road. Now the challenge is going to be whether I can do it again. You know, the first time around we were in competition with the Rolling Stones, with the Who. Now I'll be going up against bands that I've never heard of. The rock-'n'-roll road used to be like the National Football League - everybody was a known quantity. It was like, 'Who do we play this Sunday? The Washington Redskins?' Now because of videos, a band that has never even been on tour can have a number-one album. A band with no Holiday Inn knowledge at all."

I asked him if people still recognized him when they saw him. He smiled.

"Yeah, sometimes they do," he said. "But the other day, I was shopping at Marshall Fields, and these two young boys were whispering to each other and looking at me. And finally one of them came up to me and said, 'Excuse me, but are you really Boy George?'

"I'm not looking forward that much to going on the road again. I'm not drinking at all now, and if you recall, there was a time when I couldn't be more than eight inches away from a bottle of V.O.

"But I have to try, to see what happens. I don't kid myself, though - the most important thing in the world to me is being good father. Sheryl will be out of the house, and it will just be my daughter and me at home. And I'll say, Who's the best rock star in the world? And she'll say, 'Daddy!' And I'll say, 'Who makes the best records?' And she'll say, 'Daddy!'

"That's all I want, really - to be her hero. You can be a hero to millions of kids, but what you really want is to be a hero to your own."

We sat in the restaurant for hours. We talked of our time together on the road all those years ago, and of what had become of the former members of his band, and of the nature of gigantic stardom. He said that he had once met Elvis Presley in Las Vegas; Elvis had invited Alice to his hotel suite. Elvis handed Alice a gun and told him to point it at him. Alice did; immediately Elvis threw a karate move on him, and the next thing Alice knew he was flat on his back on the floor, with the gun lying by his head and Elvis's foot on his throat.

"And all I could think was: What a great album cover this would make," Alice said.

We laughed, and the talk got to shopping malls and automobiles, to potty training and cesarean sections. The waiter arrived and placed desserts in front of each of us.

Alice looked down at his.

"I don't know," he said, turning to his wife. "This looks awfully rich."

"Oh, Alice," she said. "Go ahead. Live a little."