Article Database

Discoveries

February 2003

Thanks a Billion

An Interview with Alice Cooper Drummer

Author: Gail Worley

Once Upon a time in the '70s, there was an amazing band called Alice Cooper, which included vocalist Vincent Furnier, guitarists Michael Bruce and Glen Buxton, bassist Dennis Dunaway, and drummer Neal Smith. Taking full advantage of a seminal period in rock music that nurtured a sort of "Wild West" environment for creative musical invention, Alice Cooper established the boiler plate for theatrical "shock rock."

Through the evolution of hard rock music over the past thirty years, the band's influence can be seen in groups from Kiss to Marilyn Manson. Taking their inspiration from a combination of elements such as horror movies, burlesque, androgenous fashion, British invasion bands and '60s garage rock, the Alice Cooper group created an elaborate live stage show that featured simulated executions via electric chairs and guillotines, live boa constrictors, provocative lighting effects and the horror-glam personas of the band members, all of which was bolstered by excellent musicianship.

Alice Cooper's mix of guitar-driven hard rock spiked with wise-cracking, dark humor is evident in hits such as the anthemic "I'm Eighteen," "School's Out," "No More Mr. Nice Guy" and the title track from the group's most successful album, the pre-goth classic, Billion Dollar Babies — songs that all sound as fresh and timeless today as they did when they were recorded three decades ago. In 1974, following the release of Muscle Of Love one year earlier, Alice Cooper disbanded and Furnier, who had by now legally changed his name to Alice Cooper, began a solo career. While Alice went on to have great success and enjoyed hits with albums like Welcome to My Nightmare and Alice Cooper Goes to Hell (which featured the top ten ballads, "Only Women Bleed" and "I Never Cry" respectively) the music of Alice Cooper the man never quite reached the dizzying heights of originality as the music of the original group.

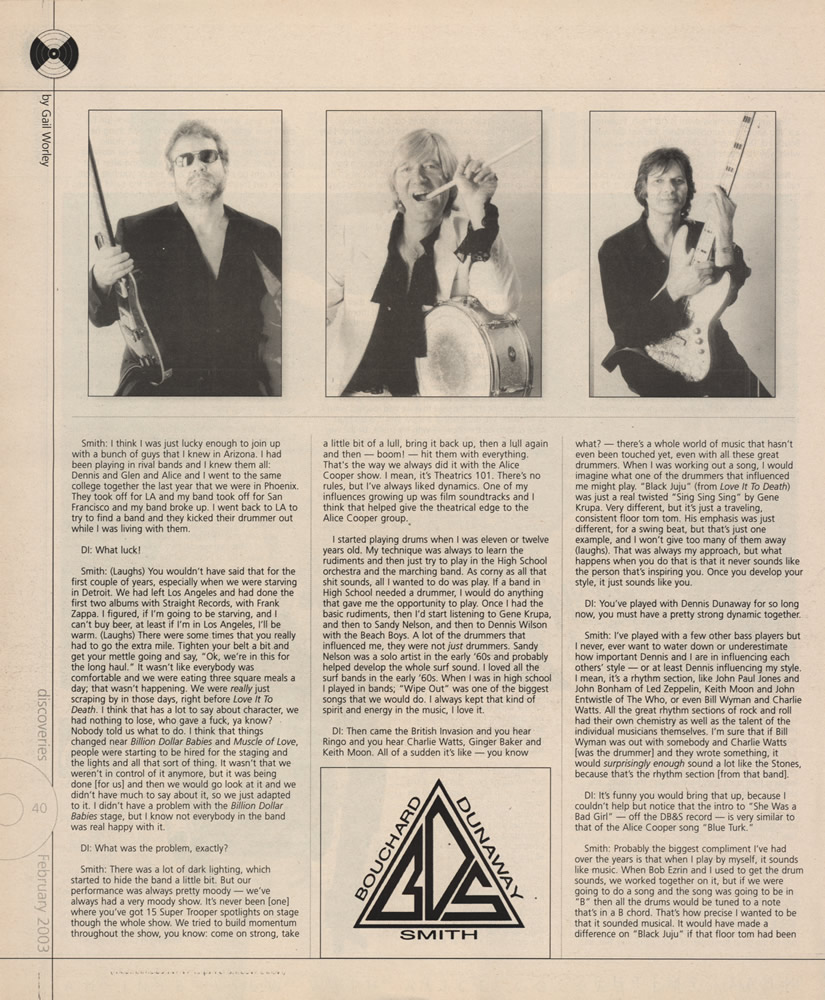

What can be said about the profound impact and musical legacy of Alice Cooper that hasn't already been said? As a solo artist, Alice Cooper continues to record new material (his latest album, Dragontown, was released in 2001) and tour with his theatrical, heavily prop-driven stage show. Likewise, the surviving band members (guitarist Gien Buxton passed away in 1997) also maintain musical careers. Michael Bruce has relocated to Europe while Dennis Dunaway and Neal Smith both reside in Fairfield, Connecticut, where the formidable rhythm section have their own rock trio, Bouchard, Dunaway & Smith, with former Blue Oyster Cult guitarist, Joe Bouchard. The group recently played a few shows in Europe, promoting their 2001 release, Back From Hell.

Neal Smith (who also enjoys a thriving career in residential real estate) recently spoke with Discoveries about his fond memories of the rock revolution he helped to instigate as a member of Alice Cooper, the far reaching pop cultural impact of albums like School's Out and Billion Dollar Babies, his own musical influences and his "lost" solo album, Platinum God. Clearly, this Billion Dollar Baby still knows how to rock.

Discoveries: Since this event is still fresh, I wanted to ask you about the European dates you just did with Bouchard, Dunaway & Smith. Where did you play and what was the reaction?

Neal Smith: It was great. We started off in a club called Le Plan, southeast of Paris maybe 20 or 25 miles. It holds about four or five hundred people. We were testing our two hour set; in the first part of the show, we do all of Back from Hell, the Bouchard, Dunaway & Smith album, except for one song. Then we take ten minutes and Dennis comes out and plays — what was the term someone had used? It was very very cool — oh yeah, "Dennis Dunaway: Mirrored Bass, Master Class." It's a bass solo, but it's all of his signature lines from "Sick Things," "Gutter Cat vs. The Jets," "Ballad of Dwight Fry," "My Stars," "Dead Babies" and "Billion Dollar Babies."

DI: Did you find it's mostly old Alice Cooper fans or Blue Oyster Cult fans that come to see you play?

Smith: There's a real heavy fan base over there, yeah. These are people probably in their forties, plus or minus. There were younger people too, but I think the majority, for this time around [were old school fans], until Back From Hell starts to get some notoriety on its own. Of course, rock is so much bigger over there now than it is here in the states.

DI: Sounds like it was a fun time.

Smith: You know, we had no idea how that was going to work. After Dennis plays his solo, Joe comes back out and starts playing an acoustic guitar to "Alma Mater," a song I wrote from the School's Out album. It's a real soft ballad, at the end [of the album] right before "Grande Finale." I go up front and sing that song, it's the only thing I don't play drums on. Then we go into "Grand Finale." It's very challenging to attempt that as a three piece, because Joe has to try to work out all the melodies with "Walk on the Wild Side" and the "Jets" song and "School's Out." It was challenging to do it, but we've worked on it a lot for about six months and it sounds really good. From then on we do the Alice Cooper and Blue Oyster Cult classics during the second set.

DI: What's that like, playing the old BOC and Alice Cooper classics with this group?

Smith: It's not really what I want to do, that's why we wrote a brand new record. Actually there are only two songs I like doing from the old catalog, "Don't Fear the Reaper," because we do such a different version, and then "Halo of Flies" off the Killer album. When [Alice Cooper] had done our second album on Warner Bros, you know, there was still that question, "Can the band really play?" I think "Halo of Flies" is the song that blew everybody out of the water. That was always something that bugged me, but (sighs), it's like Picasso and the great masters of painting. They're real abstract and not everyone gets it, but from the roots, when they're learning their craft, they have to learn the basics. You learn the rudiments, and then you go on from there. We all mastered our instruments pretty well but we just weren't playing, in the early days, what people were expecting to hear. Eventually, we started figuring out a way to merge the two together.

DI: It seems so odd to me, because everyone in the band was such an accomplished musician.

Smith: I think it's at the point now that a lot of people do realize that with hindsight, because essentially the original band was just untouchable. I mean, I love Alice and he's done great over the years, but I'm always so excited when he goes out and does great shows. Alice is one of the great frontmen of rock, absolutely. But, let's look at it realistically: when he does our stuff, it's like seeing Mick Jagger with a back-up band. Now, when I say Alice Cooper, I'm always talking about the band; if I say Alice, [I'm referring to] his solo stuff. When Alice plays his songs, I don't really care too much [who's backing him up]. They always sound pretty good to me. But when the back-up bands play our original songs, after a while I just get tired of listening to the drummers totally abort the parts I wrote.

DI: Eric Singer has been Alice's touring drummer for years.

Smith: There was one little comment from somebody that "Eric Singer can be knocked off into a cocked hat" after hearing me perform. I don't know what's meant by "a cocked hat," by the way — that was an English term. But with all honesty, it was interesting to hear their feedback. In some of the emails I've received [from fans who saw us in Europe], folks were going to see their heroes from when they were growing up. For a lot of people, in Europe especially, School's Out was the big thing for them, but then we never went back to play Billion Dollar Babies. They're thinking, "Gosh, these guys have to be in their fifties now," and we went over there and we just kicked ass bigger and better than we've ever done. I think it shocked people, which kind of upsets me because I think that the level that we had reached wasn't by accident. We did a hell of a show and it wasn't just Alice putting on the show — with my snake, by the way — and make up, which was Dennis' idea, Alice Cooper was a band.

DI: That was your boa constrictor?

Smith: Yeah, Kachina was my snake, and I still have boa constrictors to this day. She also had that album cover (Kachina is the snake featured on the cover of Killer). None of us ever had a solo album cover, but she certainly did. Only one shot out of hundreds from the photo session for the album cover came out with her tongue sticking out, and we said, "That's the cover!" (laughs). But anyway, in those days everybody had to work it on stage if they wanted to eat, so when we wrote· "Is It My Body?" that was a perfect kind of stripper/burlesque song [for our stage show]. We tried it a couple of times with Kachina and it worked great.

DI: You know there was such a weird, fuzzy transition, between the time that the band broke up and Alice went and did his own thing. It went from being a band to a solo act, but it's still the same name, and I think it was confusing for a lot of the fans. Was there any jealousy when the band broke up but Alice continued under that name?

Smith: We owned the name, but we'd just been through a big lawsuit with Frank Zappa and we weren't about to go through another one again. We had made arrangements and worked everything out, because "Alice Cooper Inc." is a corporation that all five of us to this day own. But we were too good of friends and [letting the name become a problem] was never going to happen. Then Alice changed his name legally after he went solo, and I know that wasn't an accident. You know, everybody has to do what they think is the best thing to do at the time.

Like I said, what you really saw with Alice [on his own] was Vince out there doing the best thing he could with studio musicians. In my book, studio musicians are just hired guns, like someone mowing your lawn. You hire them to do a job and after that they might go on the tour with you or you hire them again, but they're not going to be in the band forever. I mean, Charlie Watts is a member of the Stones. John Bonharn was in Led Zeppelin until he died. Keith Moon was in [the Who] until he died. Those are bands: Roger Daltrey didn't have back-up band. But because his name was Alice Cooper and the band's name was Alice Cooper — and that was intentional, nobody ever had a problem with that ‐ [it was] just the way things progressed and evolved.

Hopefully, what Bouchard, Dunaway & Smith is doing now is reaching some new levels. We had Ian Hunter come in to help us with some of the writing on a few of the songs, this is a world class band with world class writing. It's not exactly like the Travelling Wilburys, but it's sort of along the same line. We're people that have been there and done that and just love playing for the fans. If we can pick up some new fans, that's great.

DI: That was such a different time too, because bands would sometimes put out two albums a year, or at the very least one a year.

Smith: We either rehearsed, recorded or were on the road every single day. If we got into Jamaica for a show a day early, that would be our vacation. I think between Greatest Hits, which came out after Muscle of Love in I think 1975, and our first album which was out in 1968, essentially, we had eight records in seven years. Maybe it was even eight records in six years, it depends on when Pretties For You actually came out. It could have been '68 or '69. But anyway, we were certainly on track for at least one album a year and there was one year — I think it was [with] Love lt to Death and Killer that we did two in the same year. That was a lot of work, but we were also recording albums a lot quicker in those days, too, another testimonial to the musicianship of the band.

When we played live, we were actually learning from those things and we were lucky enough to translate live performances to recording. A lot of bands don't do that. Cheap Trick is an example. They did some great songs and had great albums, but Live at Budokan just blew them onto the worldwide stage. It's such a great album because of the energy they got out of it. There's really two different levels of a band: in the studio and on stage. Of course, back-up musicians never, ever have the same ability to perform on stage with the same kind of energy and enthusiasm as a full band — plus the chemistry, too [is missing]. Chemistry is so huge.

DI: What were the early days like in LA, when the Alice Cooper band was forming in Laurel Canyon?

Smith: I think I was just lucky enough to join up with a bunch of guys that I knew in Arizona. I had been playing in rival bands and I knew them all: Dennis and Glen and Alice and I went to the same college together the last year that we were in Phoenix. They took off for LA and my band took off for San Francisco and my band broke up. I went back to LA to try to find a band and they kicked their drummer out while I was living with them.

DI: What luck!

Smith: (Laughs) You wouldn't have said that for the first couple of years, especially when we were starving in Detroit. We had left Los Angeles and had done the first two albums with Straight Records, with Frank Zappa. I figured, if I'm going to be starving, and I can't buy beer, at least if I'm in Los Angeles, I'll be warm. (Laughs) There were some times that you really had to go the extra mile. Tighten your belt a bit and get your mettle going and say, "Ok, we're in this for the long haul." It wasn't like everybody was comfortable and we were eating three square meals a day; that wasn't happening. We were really just scraping by in those days, right before Love It To Death. I think that has a lot to say about character, we had nothing to lose, who gave a fuck, ya know? Nobody told us what to do. I think that things changed near Billion Dollar Babies and Muscle of Love, people were starting to be hired for the staging and the lights and all that sort of thing. It wasn't that we weren't in control of it anymore, but it was being done [for us] and then we would go look at it and we didn't have much to say about it, so we just adapted to it. I didn't have a problem with the Billion Dollar Babies stage, but I know not everybody in the band was real happy with it.

DI: What was the problem, exactly?

Smith: There was a lot of dark lighting, which started to hide the band a little bit. But our performance was always pretty moody — we've always had a very moody show. It's never been [one] where you've got 15 Super Trooper spotlights on stage through the whole show. We tried to build momentum throughout the show, you know: come on strong, take a little bit of a lull, bring it back up, then a lull again and then — boom! — hit them with everything. That's the way we always did it with the Alice Cooper show. I mean, it's Theatrics 101. There's no rules, but I've always liked dynamics. One of my influences growing up was film soundtracks and I think that helped give the theatrical edge to the Alice Cooper group.

I started playing drums when I was eleven or twelve years old. My technique was always to learn the rudiments and then just try to play in the High School orchestra and the marching band. As corny as all that shit sounds, all I wanted to do was play. If a band in High School needed a drummer, I would do anything that gave me the opportunity to play. Once I had the basic rudiments, then I'd start listening to Gene Krupa, and then to Sandy Nelson, and then to Dennis Wilson with the Beach Boys. A lot of the drummers that influenced me, they were not just drummers. Sandy Nelson was a solo artist in the early '60s and probably helped develop the whole surf sound. I loved all the surf bands in the early '60s. When I was in high school I played in bands; "Wipe Out" was one of the biggest songs that we would do. I always kept that kind of spirit and energy in the music, I love it.

DI: Then came the British Invasion and you hear Ringo and you hear Charlie Watts, Ginger Baker and Keith Moon.

Smith: All of a sudden it's like — you know what? — there's a whole world of music that hasn't even been touched yet, even with all these great drummers. When I was working out a song, I would imagine what one of the drummers that influenced me might play. "Black Juju" (from Love It To Death) was just a real twisted "Sing Sing Sing" by Gene Krupa. Very different, but it's just a traveling, consistent floor tom tom. His emphasis was just different, for a swing beat, but that's just one example, and I won't give too many of them away (laughs). That was always my approach, but what happens when you do that is that it never sounds like the person that's inspiring you. Once you develop your style, it just sounds like you.

DI: You've played with Dennis Dunaway for so long now, you must have a pretty strong dynamic together.

Smith: I've played with a few other bass players but I never, ever want to water down or underestimate how important Dennis and I are in influencing each others' style — or at least Dennis influencing my style. I mean, it's a rhythm section, like John Paul Jones and John Bonham of Led Zeppelin, Keith Moon and John Entwistle of The Who, or even Bill Wyman and Charlie Watts. All the great rhythm sections of rock and roll had their own chemistry as well as the talent of the individual musicians themselves. I'm sure that if Bill Wyman was out with somebody and Charlie Watts [was the drummer] and they wrote something, it would surprisingly enough sound a lot like the Stones, because that's the rhythm section [from that band].

DI: It's funny you would bring that up, because I couldn't help but notice that the intro to "She Was a Bad Girl" — off the DB&S record — is very similar to that of the Alice Cooper song "Blue Turk."

Smith: Probably the biggest compliment I've had over the years is that when I play by myself, it sounds like music. When Bob Ezrin and I used to get the drum sounds, we worked together on it, but if we were going to do a song and the song was going to be in "B" then all the drums would be tuned to a note that's in a B chord. That's how precise I wanted to be that it sounded musical. It would have made a difference on "Black Juju" if that floor tom had been in another note than it was. My tuning has always been important. When they had all the "chips" and that sort of thing in the '8os and everybody sounded like the same band, that's totally out the window now. It was a good experimental time, I guess, but I went right back to acoustic drums.

DI: Do you ever think back on the way the Alice Cooper band suddenly found a huge audience?

Smith: Oh yeah. I realize that, with everything that happened with the band, every bit of the way, it was all timing. There were a couple of instances with that band, where just the right couple of things in the right couple of days could have happened and it would have never been the same. The "flower power" thing from the '60s was going downhill; Bill Graham hated us, because he was one of the first people who said if [Alice Cooper] ever made it, everything that had made him a multi-millionaire with the Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead and all the bands in San Francisco was going to slowly come to a halt. He was very concerned, but that's what happens in music.

There were a couple of changes in the '70s that caused an uproar. I hated the disco thing, but I loved the Bee Gees so it didn't matter what they played. Donna Summer was great, I think they were class acts as far as the disco thing goes. But there was just so much shit music out at that time.

DI: Are there any aspects of drumming that you consider to be a lost art?

Smith: The basic rudiments, such as snare rolls. Killer was a great opportunity for me to do the death dirge on a field snare. We took the snares off the field snare so it sounded like a dirge on a tom tom, right out of any movie soundtrack, like one about the French Revolution, where they're cutting people's heads off or hanging them on the gallows. There's a song called "Return of the Spiders" from the Easy Action album where the whole song was just, (sings) "da da da da," you just keep a roll going through the whole song, emphasizing all the beats. On "Elected" I did that, too. It comes up again on the Smashing Pumpkins song, "Tonight" where you actually get back into playing your instrument, you know what I'm saying? You play your instrument as a guitar player plays his instrument. It's the difference between playing, not necessarily lead drums, but you have so much to work with on a set of drums and people limit themselves immensely. I think just getting back to the basic rudiments in drumming and utilizing them, and actually coming up with one or two of your own [can be considered a lost art].

On "Ballad Of Dwight Fry" I did something that sounds very twisted, with the organ going "da dum da dum" — it's doing the melody line. I just dropped a stick on the snare drum and let it bounce naturally. Then a couple of seconds later I'd do the same thing again. That's not in any book anywhere (laughs), but it just sounded really twisted in that context. You know, as we wrote songs, we all experimented and it gave me a great outlet to do stuff like that. That would be the one thing I would like to see drummers do a little bit more of.

DI: Maybe what's missing is just the experimental aspect?

Smith: I think that's what real music is. I mean, for School's Out and Billion Dollar Babies it was all about working with Bob Ezrin and taking our songs — mine, Michael's, Dennis' — and Alice's lyrics, putting them all together and keeping the spirit, the real twisted, sick side of Alice Cooper.

As a matter of fact Love it to Death finally went platinum in the summer of 2001. That was especially cool, because everything else went platinum except Muscle of Love — and Greatest Hits, I think is ready to go multi-platinum. Of course Alice is out there doing things and that certainly helps the sales of the catalog.

DI: How did the success of Billion Dollar Babies change things for the band?

Smith: That album was such a huge breakthrough. Billion Dollar Babies hit a level that we weren't even thinking about, ever. We were happy to have [hits with] "Under My Wheels," "I'm 18," and "School's Out." The singles kept getting bigger and bigger; the albums kept selling more. All of a sudden, Billion Dollar Babies hit and, in 1973, we're one of the largest grossing tours in rock & roll. We had our own plane, we had it all. In March, Billion Dollar Babies was number one in Cashbox, Record World and Billboard in the same month. Not too many artists — even one of the biggest artists in history — have hit all three charts at number one at the same time. That was when, I think, anything we'd ever dreamt about was surpassed. You can have dreams, you can be focused and you can do things, but when you go beyond that dream, that's what happened on the Billion Dollar Babies tour.

DI: Donovan sang the co-lead vocals on "Billion Dollar Babies." How did that happen?

Smith: We recorded that in Morgan studios in London, and Donovan was recording in the same studios, in an annex across the street. He was right there when we were doing this back and forth vocal part and he was cool enough (laughs) to come over and do it [with Alice]. Of course, Donovan was huge as far as we were concerned, with the British Invasion and his music in the '60s. He came over and helped us and we thought that was really, really cool of him.

DI: It's a very un-Donovan sounding vocal.

Smith: He did a great job and that's what's cool, that's what happened with the energy of what became Alice Cooper. Anybody gets in that studio and it just gets twisted, but it gets twisted in a good, creative way, and you could feel free to experiment doing whatever you wanted. It was an environment that was just great to work in and it was never forced: it just flowed. So, yeah, that was very cool that Donovan did that. A lot of people might not know that was him.

DI: Tell me about the Platinum God album you recorded in the '70s but didn't release until 1999. Why the long delay?

Smith: After we had been in South America in early 1974, we decided to take a year off, and there was a lot of soul searching going on. Michael Bruce wanted to do a solo project. Michael was really a student of the Beatles, as far as how his songwriting went, his chord structures. For many years we had been taking his songs and turning them into Alice Cooper songs, and he wanted to do some stuff and wanted to release the songs in their original form. Obviously, that gave both me and Alice the opportunity to record. Alice did Welcome to My Nightmare and I did Platinum God. I took Platinum God around to some places and didn't really get a deal for it. Then Mike Bruce got a deal in Europe to release his record, so In My Own Way was released and then Welcome to My Nightmare. Those three albums were all recorded at the same time.

I dug the tapes out after Glen passed away in 1997 and we all started to realize our mortality. Since I've had my website for six or seven years, I keep getting email from people who want to find out what happened to Platinum God, because it was written about in the fan and trade magazines and never released. I said, 'well, I'll put my own label together and it'll be available.' There were two songs, two stereo bed tracks that I had found in 1999, that I never finished, and I went back and listened to them. I didn't have the original masters but it was a very clean track and it was all rhythm guitar, bass and drums. I was hoping there were no vocals on it and no lead guitar, and there wasn't. We went into the studio and put it into a digital format. Then Richie Scarlet came up and did some lead guitar work on it. I finished the lyrics on both songs; one of them is "Maneater Deadly to Her Prey'' and the other is "The Seas a Maneater," a similar song.

We re-mastered everything, remixed it, re-EQ'd it and I made a couple thousand copies and started selling it on the Internet. I took it over to the UK with me when we were just over there and a lot of people bought them. It's been sort of a collector's thing and it's fun. But it was unfinished business. I was totally shocked when Glen died and I figured there were a couple of things I wanted to finish up in my life and one is Platinum God. I wanted to at least make it available to the people who cared about it. It's a very nice package.

Jack Douglas, who had produced Aerosmith, was in the studio with us [for the original sessions]. He' d produced Muscle of Love with Jack Richardson. When we were doing that album, I'd asked Jack if he'd be interested in working with me on the project and he was. Some of the things were a little bit too experimental for him and I wasn't happy drum-wise. But then on the actual song "Platinum God," [he was agreeable to] anything that I wanted to do or experiment with, that song was the huge launching point for me. It mixed a song with a soundtrack, essentially. When I hear a song I really like, I always see a visual with it. I'm very happy that the album is done.

DI: When did you get into real estate?

Smith: I've been doing it since the mid-eighties. It gives me the time and the flexibility to do music, but still have a career in real estate. Of course, the whole band moved from Pontiac, Michigan to Fairfield, Connecticut in 1972, because that's when we started recording "School's Out." Then Dennis and I never left, Michael had gone out to Lake Tahoe, Alice went to, I think, Chicago and Glen went back out to Arizona. I love it here, but I go out to the southwest once or twice a year and Alice and I get together. We all visit each other all the time, we just saw Michael over in Europe. When I was in Arizona for a couple of weeks in February for a long vacation, Alice and I played golf. We have a great time every time we're together, and we reminisce and tell some cool stories. Everybody gets along well and we never wanted to have any of these nightmares like you hear happen with some bands. We're like family.