Article Database

Creem

January 1972

All American

A Horatio Alger Story for the Seventies

Author: Lester Bangs

Looney Tunes

"What kinda dog is that, anyway, Mister?"

"It's a cross between a Manchurian yak and an Australian dingo."

W.C. Fieldus, selling a ventriloqual dog in Poppy

COOPERTOON #1: "Return of the Spiders" is playing, And here stand these two Stooges in the old sense, not like guitar hoodlumps cut from Ig-patterns, but just old time disgraced schmozoes, except that these two schmozoes are listenin' to this here rabid, highballed motherrhinofuck of a record. And one stooge looks at the other one with a pained expression on his face and sez: "Ugh, what loud unnerving shit! I couldn't stand to be around music like that for more'n a couple of minutes before my nerves'd come unstrung! And not only that, but you actually tell me it's the first thing you like to play when you get up in the morning! You must be deranged!"

And Stooge 2, the one with the taste, why he just turn and look at the other one all sly with his eyelids half-cocked down and purr: "I find it rather bracing myself "

And there you have it. That sense of disjuncture and harmless abrasion is what Alice Cooper's all about, I think. On the other hand, it might just be that Alice is actually conceived and founded on nothing more outre than plain ol’, good ol', reassuring ol' Show Biz. Entertainment. And Alice's approach to it, far from deriving from any architectonics of Future Shock, actually draws gleefully on the most venerable, storied, sanguinely plebian of the lively arts. It draws on Vaudeville and carny and pies in the puss and the baggy pants hitting the sawdust and the bearded lady. And circuses and animal acts and all that superficially wholesome stuff stuck on independent channels that your parents while away their tube hours soaking their nerves in. Mr. Bones, the Beggar and Mrs. Davey, Honest Old Uncle Alice and his Sequin Flapping Drag Brash Cartoonoroony Whoop-up. Take the family.

So how do we resolve the contradiction? Well, for one thing, it's easy to carry garishness too far. Alice's intricate stage business and sonic assault is an exercise in tactical brinksmanship on several levels. The drag stuff carried over from being truly outrageous, with Alice looking enough like a rather reptilian Vegas hooker that a drunk businessman could've took him home for the surprise of his life, and wound through permutations of business over the years until it had petered to the spider-eye makeup and aluminum cocaine jumpsuit zipped open to the navel.

All the props and trappings and '30s Horror Movie settings have a specific mileage beyond which they muddle downstream into shuck-and-jive. But Alice and the crew, consummate technicians that they are, almost invariably tether the gimmickry and injection hysteria just a shadow's breadth this side of Gehenna.

On the other hand, maybe Gehenna is where it should really be their job to take us, rather than the Laugh in the Dark ride at the amusement park. I think that's something like what Iggy tried to do, and look at the Stooge era: done too soon. But just maybe there's a bit of cautionary parable lodged in that great success-and-sharp-plunge story, and that is that perhaps the only growth possible for an artist who doesn't remove himself at all from his art, so that it and his life are identical (because Iggy didn't and for awhile they were), is a tailspin into welters of egocentric, relentlessly solemn self-consciousness. Especially if the artist is trying to render or conjure Gehenna, the pit, the darkness of chaos and disintegration.

The incandescent human demon personifications like Iggy, or more appropriately like the image that Iggy projected, bring to mind- the old Dylan song about the house on the hill that was "brighter than any sun," and "Don't go mistaking paradise/For that home across the road." 'Cuz if you do you'll not only wreck your health and lose your apple cheeks and vimchocked profile, but your sense of humor as well! And that's the worst fate of all. A much more sensible course, after all, than taking it upon yourself to live out all the dark impulses of the human soul, is just to pull a pretzel turnabout and become Alice Cooper instead.

And really, I don't think anybody has ever seriously invested in Alice the expectation that he should enter the flames and get seared himself just like the tortured Dwight Fryes of his songs. A good case could be made that Alice is just dally-dabbling in the Deep, and that his actual involvement with what he's putting forward (and not just the obvious sexual elements) is most likely about as demoniacally driven as Jim Morrison's must have been late in the years, when ol' botabelly would come lurching on to sing "Celebration of the Lizard" to an opera house full of bigeyed pubies.

Alice doesn't have a beerbelly (yet) but you can bet your chrome-plated Led Zeppelin dildo he's wholesome, a contention I'll attempt to shore up with a few facts and figgers when I pass over into the Tiger Beat meat-and-spuds of the article where you'll meet Alice and the boys in the band and even (sorry to disillusion any diehard hopes) their old ladies. Maybe. I may restrain myself from spilling too many beans since at least one member of the Cooper Rancho (namely, Alice's svelte sweetie, Cindy) sort of semi-specifically asked me to leave her out of it or at least (and here come COOPERTOON #2) in the background:

In the kitchen, maybe, or out in the parlor washing windows with all the idiot glee befitting some TV stereotype of the unliberated drudge. Yes folks, not only does Alice Cooper dress up in women's clothes, he also exploits the woman he's got! Every night when he gets home from the concert and kicks back into his favorite overstuffed TV chair, Sandy has to approach him cross the carpet on all fours, reverent with scripted trepidation, swathed in the threads and cap of a suacy French scullery-maid, and slowly and respectfully remove his red spike heel patent leather Capezzio pumps! Kneeling at his feet, she then must unsnap and peel off his pantyhose, being tactfully watchful not to cause the exhausted Star the slightest discomfort, after which she worshipfully massages his shaved legs and sweaty feet for a few minutes, just to get the workaday weariness out of them, after which she serves him his pipe (pure Tangeirian kif) and beer (Blatz) and then proceeds to undo his hot-pants, dig beneath the filmy black panties inside, delicately scoop the famed Al Coop porker out and lower her ruby lips with a slowness and precision whose mastery took many, many months of schooling and unbending discipline, the cat-o-'9, the tongs, the . . . (fade out to obscene Burroughsian Mugwump gurglings; and the most obscene thing about them, incidentally, is that they come out sounding to the attentive ear not like indescribably esoteric and squishily amphibious sex acts but the most pink-tickled geyser of gleeful and near-uncontainable laughs. What a dirty trick!)

As I was saying before the porn break, though, the fact is that Alice Cooper is really one of the wholesomest, cleanest, most upright and well-spoken Popstars you'd ever care to meet. Just a real all-'round nice guy ! The perfect cherub-cheeked picture of a God-worshippin' pie-scarfin', parent-respectin' ALL AMERICAN BOY!!!!! (His parents even attended one of his shows, and loved it.) And that straight-ahead lucidity can't help but carry over a bit, cross the slimy footlights into the arena of Alice the galvanic Stage Exorcism. It's good rock, good theatre, good Alice charisma, but it's not a real nightmare. The thing about a nightmare that can really nab you by the nuts and hang you heels up in total helplessness is that usually you don't know it's not real, only at the very end maybe does the conscious mind come Jimmying in and shatter the set. And Alice Cooper's nightmares - I'm thinking of Love It To Death in particular and the stage act in general - never take over their structures to become obsessions with dark lives and wills of their own.

What Alice's little Gothic scenarios are really is something else entirely; what they are is cartoons. And that's almost as great and important as if they were the other thing.

COOPERTOON #3: It's 1960 or thereabouts, and the "late bloomer" Alice, who kept watching afterschool cartoons all through his young manhood and still does today, is catching a Bugs Bunny sequence in his Phoenix parlor; Panorama of darkie silhouettes swinging hammers, tightening screws while singing "I've Been Workin' on de Railroad." Cut to Bugs Bunny lounging-in a hollow stump munching a carrot and reading a girly magazine. Elmer Fudd comes down the path singing "I've Been Workin' on the Railroad" in a broken voice. Bugs looks at the audience, bats the long lashes he has suddenly grown, and simpers: "Why, that sounds just like Frank Sinatra!" then disappears into the stump. Fudd sets up his surveyor's telescope right in front of the stump, looks in and flips his lid when he sees a montage of cheesecake and black nylons from the magazine Bugs is holding in front of the lens. When Elmer leans around the telescope to get closer to the chicks, Bugs not only has long lashes but lipstick as well, purrs: "What's up, big boy?"

"It's the wabbit!" screams Elmer in a paroxysm of rage at having his masculinity compromised by his arch-nemesis, then chases Bugs who turns into a torpedo zooming through the air and straight down the nearest rabbithole, into the mouth of which Elmer inserts the muzzle of his rifle and fires off a spasmodic volley of bullets. When he gets back to his telescope and looks in, Bugs holds one lit match in front of the lens and Elmer sees the whole forest burning, shrieks "Fire! Fire!" Hooks and ladders erupt from Bugs' stump, Bugs climbing up in full fireman's uniform and hat, with a hose in his hand whose jet he turns on Fudd full force, blasting him back until he finally manages to grab his gun, chase the anarchic bunny back to his hole and fill it with a few more rounds.

When he gets back to the stump, his telescope's place on the tripod has been replaced by a straight, rigid Bugs Bunny. Elmer peers into his eye, frowns: "There's something awfuwwy funny going on here!" In reply, Bugs grabs him, plays his lips with the classic cartoon SMMOOOCH!! and runs off hooting like a hooligan...

Not only is that what Alice Cooper at his best is all about, but it would be incredible if he were even half as subversively effective as Bugs Bunny in putting his beFuddled audience through changes. They even work for the same company, though that is probably not the reason why the cartoon element has always been in the music for anyone who cared to look. Even when you couldn't understand the words, the wheedling falsetto vocals and jerky razzmatazz structures of much of the stuff on the first album's second side point to a very specific, caricaturial king of whimsy. And the very first song on Easy Action consolidates and confirms it — just dig the instrumental section, right after "Mr. and Misdemeanor," that romantic twosome, have finished watching the sun set together: the solos and scales are melodramatic, exaggerated and ballooned towards precise burlesque, and you can instantly see the leering villian or be-caped Mr. Hyde slinking after Little Nell with stealthy high steps. Lucky Luciano is in there too, and later, in "Still No Air," the whole West Side Story episode, complete with direct cops (''When yer a Jet yer a Jet all the way/From yer first cigarette to yer last dyin ' day! Eeeasy, Action! Gotta rocket — in yer pocket!!") is so blatant and hilarious that only the technical sloppiness keeps it from being a real classic.

And the interesting thing is that so many people, initially or ideally, should find these cartoons so abrasive. But then, what were all those old strips, from Bugs Bunny to Popeye, about if not pain? Not a frame passed that somebody wasn't getting conked on the bean, shot point-blank (which just singed and turned them into Niggers), or dropping off the 30th story. It's fun to dig the tribulations of our fellow men in that context, we eat it up. And when it's all wrapped up in a whirling storm of guitar noise, it feels even better. While I can't go as far as Dave Marsh who sez that "Sometimes the tenderest thing you can do for a person is smash them right in the teeth!" I do think that we need stars and heroes able to rattle our bones and sear our brains a bit.

People who call all this darkness and negativism are merely shortsighted, if not certified candidates for white and red canes. The Stooges were the ultimate Nova blowtorch of savage nihilism, but Alice Cooper has recognized it as his function to take some of the irritation, hostility and paranoia around us and demonstrate that it can be capitalized on and transcended with glee if we're just dementedly lucid enough. And the attendant sense of abrasiveness is nothing that'll ruin ya, Lilly Liver but just jarring enough to be, as in the tale of two stooges, bracing! I have wondered on occasion whether it might be possible to transcend the ingrained reactive recoil and get to the extraordinary musical rush that lies somewhere inside the creaking squeak of chalk on a blackboard; I do know that for years I've found the great grindings of metal in factories or the sizzle of a welding torch an interesting and sometimes positively lulling form of muzak.

And speaking of electric sizzles, it's also crucial to recognize that the Alice Cooper vision issues not only from cartoons, but from a deep love and understanding of TV in general. We all grew up primarily on two things: rock 'n' roll and TV. Alice Cooper was the first rock group to recognize that fact and fuse the two influences in a big way, and nobody'll be surprised if the curtains part someday on the whole band riffin' in some monster Sony. They almost made the real thing already, via an Excedrin commercial and LA kiddie show which were both axed.

But omens of future glories do appear occasionally. When I first took up residence in the CREEM mansion, I was ushered to my room and: there was a TV! My very own! My first very own boob toob! My idiot box, my baby! Cute as a sow's tongue. I took to leaving it on all the time, since the steady high-pitched buzz of the TV tube is merely the most exquisitely refined electronic cousin to the hymn of feedback flowing strongly through our nervous systems, and whenever I entered the room to get something or was just wandering vaguely around I would stop and watch a short snatch of the current program. Learn a lot that way, and just like with a Burroughs cutup or Lucky Luciano bringing "a modern mosquito/To every big city" I don't mind the disjuncture at all. One Monday night I happened in on an episode of Mayberry RFD: it was about an amateur talent show in the quaint burg, but my ears turned backflips when I heard the yokel MCing the thing drawl brightly: "And now — our 14th contestant of the evening, a sweet li'l ole gal you all know from over Bear Mountain way — Miss Alice Cooper!!" And then there materialized the most sweet-temperedly purse-lipped stereotype of a Saltine States old maid you ever saw, practically falling backwards behind this vast tacky gilt-flaked harp. She smiled demurely, lifted one limpid wrist, and...

Startime!

"It is the phantom spirit of a leering Artaud hissing through the veins of an amphetamine age, gushing forth his geysers of grotesque gargoylerie upon the hapless heads of a public so numb it can scarcely respond with a piteous terminal twitching."

— "Purging the Zombatized Void with Alice Cooper," by Marvin H. Hohman, Jr. CREEM, Vol 2 No.14

A thundering bass chord, a flash of brimstone light, and Alice Cooper are revving up their War of the Worlds cylinder for your terror and titillation. Which it'll be more of has been oft asked indeedy, but at this point the initial blast of sight and sound obliterates all yer schoolass either-ors. Some design to limn it into the famed History of Art, others attend from nervous curiosity, but no one can deny that even if Alice ain't the hardest workin' man in show business he does aim for a Hippodrome of the sensibilities.

Opening the can with "Sun Arise", Aussie Rolf Harris' 1963 hit derived from aboriginal folk forms; the tribal chant hits passing strange. Especially since it issues from five lunar apparitions with hair, longer than parental nightmares ever dared conceive, falling around ambiguously painted faces — Halloween, drag ball, or war-stripes? — and scrawny shoulders to halfway down even more ambiguous torsos curving and swooping outrageously as late-50's Cadillac tailfins in sheer glitter-spangled uniforms of gleaming astronaut silver which run, fashionably one-piece and as many sizes too small as Mamie Van Doren's sweater in High School Confidential, straight down to shiny and almost as fashionable women's patent leather shoes. The initial impact is, without qualification, weird. And perhaps unsettling. Alice leans over his audience sizing them up with a bigeyed hoodoo stare, beating the sharp chunks of the dawn rhythm on a woodblock, and song and band combine to fill the air with a heavy sense of ritual, paradoxically primordial and sci-fi at the same time. Prehistory and the technological junkyard forming a perfect circle to frame a beginning as vividly theatrical as the sense of cultural bucket-kicking reveled in when the Doors kicked off their career with "The End." Which is just one of the more obvious ways Alice Cooper point out to us that they are to the core about not terminal-planet deathroons ala Burroughs and Stooges, but rather all manner of beginnings or at least transitions.

Which is one reason their audiences consistently respond with such ravenous joy, seldom failing to at least make the motions toward reciprocating and giving Alice the show he wants, i.e, if they were just a tad less self-conscious or barbiturated they'd be as wild as JD audiences of legend, yowling for their hero with glistening eyes, a surging human sea feeling its oats if not knowing quite where to slingshoot them. These are the kids who don't cringe defensively when Alice swishes up from "Sun Arise" into "Is It My Body?" For some it may be a pop device for measuring and confirming the strength of their own (straight) sexual identities by remaining hiply undazed by Alice's bump-and-grind (which is ironic and may be a measure of the band's failure to fill out the proportions of the deconditioning agent they seemingly would like to think themselves), for others just a highspiritied exercise in Bizarro-for-its-own-sake, for others maybe even a physical turn on (though that's more doubtful). In any case nobody walks out anymore when Alice climbs into his Queen carriage and camps up full-throttle, moueing lips like Vogue models and young girls putting on their makeup do, wiggling and mincing past Mick Jagger if finally somehow not as convincingly, every enlightened citizen's stereotype of the slithery, lisping Homo. He even takes off his stacked-heel shoe and teases the audience with the promise of a fetish-souvenir just like Mick used to swing his sportcoat around his head in 1965, and of course the shoe is never thrown either. (Too early in the show, as someone once said when pondering Iggy throwing that piece of dogshit at the audience in New York — bad theatre.) And, O shades of Mamie Van and Jackie Curtis, winds the song up with clockwork Thirties star move, pulling his jumpsuit down to expose one thin shoulder, roll his eyes and simper "I didn't know you cared" to the gales of delighted applause.

The show, while reforming itself constantly as bits of business drop out and others appear if only for one night, remains through entire tours within an exoskeleton whose dimensions are roomy but rigid. Some major props and routines run with only very minor changes for months (that fucking electric chair, Jesus...), and the selection of songs varies almost never. This summer they did nothing live from their first album and only one song, the encore, from the second. Everything from Love It To Death except "Long Way To Go" plays currently, building to a long, intense closing section juxtaposing the nightworld panels of the "Second Coming-Dwight Frye" sequence with "Black Juju's" Gehenna-moralizing, then roaring back in encore to dissipate all cumulative tension with a super rave-up "Return of the Spiders."

The playing is always loud and stunning, like being hit and run over by a mountainous chrome bumper piloted by hooligan fiends straight out of Frederick Wertham's nightmares; the very metallic inhumanity of the sound at its most basic level ensures absolute impact and surreal resonance. What you occasionally miss, though, is the primal sense of rock 'n' roll as MEAT JOY, from Little Richard to the Stones. And that sense is in Alice Cooper, too; it's just that at present it only seems to issue on nights of special audience-band interaction, when each is digging the other so much they're about gimcrackery and lays it down solid, brother, like a rippling sheet-metal highway you can cruise out on forever. And such nights which I have seen have given me some of the surest and most exalted rock 'n' roll chills I've known since the early days of the Stones.

On the other hand, it's pretty hard to extract diddleybop from things like "The Ballad of Dwight Frye." With the first piano-school stanza of "Second Coming," the five actors start filling in a steadily-darkening Gothic landscape, from purple nightshade to the shattered pitch at the heart of Dwight Frye's dungeon. The old Universal horror flicks made in the 30's with Karloff and Lugosi, from Frankenstein and Dracula to The Black Room, had no background music either because the primitive sound cinema had not reached that point yet or because the producers thought they'd haunt deeper that way. These songs and "Black Juju" are the belated soundtracks to those films, created by war babies who couldn't help but conceive them as cartoons.

The bogeymen have gone through several metamorphoses in the past 40 years, though, and jump from different doorways now. Dwight Frye was the journalist in Dracula who came to call upon the Count and ended up icy-mad, the sole survivor on a shipful of bloodless stiffs, glimpsed unforgettably at bottom of hatch with poisoned eyes glittering up at the creaking laugh: Ha-haaa-haaa-haaa"—- later confined to victorian nuthouse where he called daily for meals of flies and spiders. Alice's Frye is more akin to Kesey's McMurphy, the universal late-modern paranoic fantasy of sane to himself incarcerated in a malevolent Orwellian bughouse.

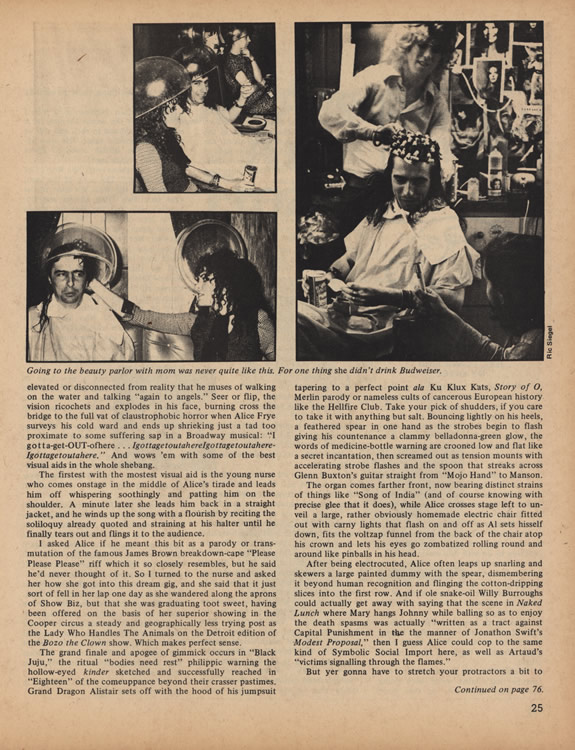

And the interesting thing is that it all seems to wind with supreme dark logic out of a lyric collage of images from Christian myth, from "Hallowed Be My Name's" antichrist or borderline-La Vey assertion of personal Godhood rubbishing the heritage of Theocratic authoritarianism, through "Second Coming" which suggests that the protagonist is so spiritually elevated or disconnected from reality that he muses of walking on the water and talking "again to angels." Seer or flip, the vision ricochets and explodes in his face, burning cross the bridge to the full vat of claustrophobic horror when Alice Frye surveys his cold ward and ends up shrieking just a tad too proximate to some suffering sap in a Broadway musical: "I gotta-get-OUT-ofhere... igottagetoutahereIgottagetoutahereIgottagetoutahere." And wows 'em with some of the best visual aids in the whole shebang.

The firstest with the mostest visual aid is the young nurse who comes onstage in the middle of Alice's tirade and leads him off whispering soothingly and patting him on the shoulder. A minute later she leads him back in a straight jacket, and he winds up the song with a flourish by reciting the soliloquy already quoted and straining at his halter until he finally tears out and flings it to the audience.

I asked Alice if he meant this bit as a parody or transmutation of the famous James Brown breakdown-cape "Please Please Please" riff which it so closely resembles, but he said he'd never thought of it. So I turned to the nurse and asked her how she got into this dream gig, and she said that it just sort of fell in her lap one day as she wandered along the aprons of Show Biz, but that she was graduating toot sweet, having been offered on the basis of her superior showing in the Cooper circus a steady and geographically less trying post as the Lady Who Handles The Animals on the Detroit edition of the Bozo the Clown show. Which makes perfect sense.

The grand finale and apogee of gimmick occurs in "Black Juju," the ritual "bodies need rest" philippic warning the hollow-eyed kinder sketched and successfully reached in "Eighteen" of the comeuppance beyond their crasser pastimes. Grand Dragon Alistair sets off with the hood of his jumpsuit tapering to a perfect point ala Ku Klux Kats, Story of O, Merlin parody or nameless cults of cancerous European history like the Hellfire Club. Take your pick of shudders, if you care to take it with anything but salt. Bouncing lightly on his heels, a feathered spear in one hand as the strobes begin to flash giving his countenance a clammy belladonna-green glow, the words of medicine-bottle warning are crooned low and flat like a secret incantation, then screamed out as tension mounts with accelerating strobe flashes and the spoon that streaks across Glen Buxton's guitar straight from "Mojo Hand" to Manson.

The organ comes farther front, now bearing distinct strains of things like "Song of India" (and of course knowing with precise glee that it does), while Alice crosses stage left to unveil a large, rather obviously homemade electric chair fitted out with carny lights that flash on and off as Al sets hisself down, fits the voltzap funnel from the back of the chair atop his crown and lets his eyes go zombatized rolling round and around like pinballs in his head.

After being electrocuted, Alice often leaps up snarling and skewers a large painted dummy with a spear, dismembering it beyond human recognition and flinging the cotton-dripping slices into the first row. And if ole snake-oil Willy Burroughs could actually get away with saying that the scene in Naked Lunch where Mary hangs Johnny while balling so as to enjoy the death spasms was actually "written as a tract against Capital Punishment in the manner of Jonathon Swift's Modest Proposal," then I guess Alice could cop to the same kind of Symbolic Social Import here, as well as Artaud's "victims signaling through the flames."

But yer gonna have to stretch your protractors a bit to chart the deep import in the grand climax, where Alice swings an arclamp around on it's cord, the beam splashing through the audience, and the band pushes everything up to the screaming ceiling as Mike Bruce dons a gasmask and runs wildly across stage blasting away with a compressed air tank on full-force as Alice shakes pillows slit on one end and a thick storm of feathers fill the air creating total pandemonium, settling in the scalps and eyes of the first dozen rows and on the footlights to burn with a stench reminiscent of unspeakable Beelzebub cookeries in mossy glades of the Dark Ages or at least the smokepots the Iron Butterfly used to employ to give their act a little mystik klass.

What a show! And the encore is usually even better. The first time I saw it Alice worked his audience to frothing peaks of frenzy by waving a series of rolled posters of the band at them like magic batons and then tossing them at random to lucky souls in front who clawed and scrambled like, to use a really sexist metaphor, housewives at an hour-long shoe sale. The next time I saw the show he augmented the posters with a fullsize supermart shopping cart, which some lucky soul probably used to wheel a beyond-the-pale buddy home, and the last time, in a great show at the Eastown ballroom in Detroit, he did away with the posters altogether and substituted money. And that, brothers and sisters, was a night to remember. Here's Alice bobbing on the balls of his feet, baiting the crowd with a fat fistfull of dollar bills, tossing one out, then another, but holding back with absolute puppeteer precision until he finally got what he'd solicited for so long and they stormed the stage in some Bizarro hippie Let's Make a Deal apocalypse, and one hair-trigger second short of total dismemberment Alice flung the wad of green as far into the audience as he could, creating at least a half dozen more scuffling whirlpools of greed.

You might call it obvious, but it shore is a sight to see. Or as Alice sang in "Mr. and Misdemeanor," "Lawdsakes and land o' Goshen, who put all of this in motion?"

Whatever the answer, it sure ain't Antonin Artaud. Any clear eye can see natural as the Good Humor Man's tinkle down a windy street that Alice Cooper is nearly nothing wouldbe intellectuals, refugee legion from gloomy seminars, have stapled onto the music. Alice has so far transcended Artaud's wracked victims signifyin' from the entrail-strewn fryin' pan of the Theatre of Cruelty that contemplation of the matter is most to laugh as poor old Antonin could so seldom. But then, maybe if he'd grown up with Superman and Bullwinkle instead of his mouldy hovels of Gallic fatalism he'd be in on the shared Big Little Joke too and we wouldn't have to say, as Libby the Kid doth to Mean Gene: That's why you're no fun!"

The Fax: Refrigerator Heaven to Pontiac Farm

"My name is Judas. My friends call me Pan. I left my home when the plum trees blossomed... I'm looking for love. I'm looking for trouble."

— "Across the Great Divide," by Paul Williams, Fusion #59

Arizona is a fascinating state, in a way. Not the least fascinating thing about it is that it is so barren, vacuous and generally uninspiring that you might well sprain your brain struggling to divine what it could possibly have that would keep people there. Senior citizens, yes — they fit snugly into the berths prepared for them, those vast, uniformly colorless housing projects slapped up on the desert floor and often punctuated by nothing more than the occasional strategically located shopping center and gas station.

How anybody with any sass and vitality could take such surroundings, however, is incomprehensible. Every last house in the state except some of the 'dobe shacks of no-'count Mexican laborers bears an enormous air-conditioner on the roof or side. And those air-conditioners, like the air itself, verily like unto skag for junkies, are an absolutely essential fixture of existence. They are the only thing standing between the citizenry and the merciless incursions of a summer sun which sears and stuns everything in sight so that most folks barely set foot outside for several months of the year, except to climb in their air-conditioned cars and drive to refrigerated markets and lay in more supplies. It's a mole/scarab existence, I guess, and you learn to find your pleasures wherever you can. What aspirations to culture the place claims are mostly summed up in Arizona Highways, an expensive Kodachrome magazine with lots of full-page vistas of purple mountains and endless varieties of cacti. The sociopolitical bent of the entire state is unquestionably Right Wing, and even in the bowling alleys they have signs on the pinball machines that say: "No One Under 18 May Operate this Machine Under Penalty of Law — Sheriff."

So whattaya do growing up in a place like this if you're a bright, inquiring kid like Alice? Where under that seething tyrant of sun can you turn for guidance? To the TV, that's where! "Sit your smart kid butt down there and learn, son," quoth Alice's father, who may have been a Baptist minister (yep, that's right) but was also a Pop of uncommon prescience, except he didn't call him Alice of course because at that time his name was Vince. And Vince obeyed in spades. In fact, TV was unquestionably the first and maybe consistently strongest influence on our rock 'n' roll wunderkind and quite probably the rest of the band as well, which was why he could say years later, in the flush of success, that: "Blues and blues-based music never really figured at all in any part of our development. I wasn't really exposed to it when I was growing up, or even until much later, when I was in college. But I've never really minded much because it's hard to see it as anything you'd worry about missing. I mean, I was way more influenced in the whole thing, my personality, my attitudes, even my approach to music, by all those late-50's TV private-eye shows like Peter Gunn and Richard Diamond and 77 Sunset Strip and Johnny Staccato with John Cassavetes and all the beatniks in Greenwich Village — remember that one? It was great! Almost every week in TV Guide there'd be a character listed for it that was just called 'weirdo,' and they were all different guys, start shooting the new script and say, 'Wait a minute, we need one of those again, go get one,' and go out and bring on another Weirdo... I wondered maybe if they had a Weirdoes' Union or something... but what I was gonna say before, was that all that kind of stuff was much more important and influential to us in our formative years, than any kind of specialized musical trips. We listened to Elvis and Chuck Berry and whatever was on the radio and mixed it up with 77 Sunset Strip and got Alice Cooper."

After teething on TV it was art school, and, for Alice himself, studying with a lady hypnotist in Phoenix who enlightened him to the trinity in every sentient bod; namely, that we all got both men and ladies and even blessedly never-shaken child in us. Which, according to legend, was the inspiration of the whole "Alice Cooper" persona. But playing around Phoenix at various times as the Spiders and the Earwigs, the boys never broached the Perve swishes of their L.A. venue — the Sheriff of Cochise woulda had 'em in the hoosegow so fast they might never have dared to strangen the stage again and woulda withered on the Yucca into steel-guitar hippypokes. The only report tracked down of their early Arizona shows spoke of Alice leaning through a window sill held in his hands, wanking out some real Psychedelic blather about leaning into the windows of yer mind.

Luckily for all of us, they soon migrated to that storied town of Fat Angels, mouldy hormone-gorged stars and every stripe of tinhorn hustler, and proceeded to make a quick name for themselves at the then-cresting rash of Free Concert Love In Powwows in the closest available park. Alice elaborates: "We've always been into liquor but at that time it was almost the biggest thing in our act. We were into getting falling down drunk and then going out to play those love-ins, where you know everybody was really into the whole consciousness of this new dope scene and walking around saying 'Groovy' and 'Oh wow' to each other and making that particular social scene, which we never put down at all, it was just that we had our own scene, and right then our big thing was wine. Everybody's probably seen that picture they printed in Rolling Stone and the Free Press, I think, where we're playing in the park and I'm jumping up and down beating on a gallon jug with a drumstick. But a lot of the kids were still at the stage where they were very puritanical about alcohol, and our main approach then was just to get as fucked up as possible and go play and see how obnoxious we could be. Just to create any kind of absurd disruption of that, what, sylvan sort of placidity we could. And it worked, it was great fun. People would walk around in circles saying, 'Wow do these guys suck, who the fuck are they?', and some would come up later and ask us why we were trying to bum everybody out.

"One other thing is that at the time our music was almost total noise, no real order at all, and lots of people didn't like that too much either. But we did, and we kept on, and every once in awhile somebody would come up after we finished and say they really dug what we were doing, and we'd give 'em a swig of Red Mountain. Some of them were like intellectual types who tried to talk about atonality and chance music, but lots of times they were bikers who'd give us their wine or offer us some downs and tell us what a bunch of lames they thought all the hippies were. I think they really identified with the music we were doing better than anybody else, because it was so noisy they heard motorcycles in it."

With such an auspicious debut in Smogtown, the A.C. group, never laurel-squatters, gained confidence and quickly set about modifying the show. The next phase was the promulgation of onstage violence, half planned and half spontaneous. A bit reminiscent of the Who, as is much of their sound, but the Who never got reactions like these. Neal Smith grins sardonically and recalls: "I'm not positive, but I think it might have started one day when this fat girl, jumped onstage and started coming onto me, right in the middle of the set. Here she is sticking these enormous tits in my face until I can't even concentrate on playing the drums at all, and what's more I think she was mainly doing it just to see if she could break in on our trip as much as we were on some of her friends in the crowd -— not like she was offering herself at the temple of Rock 'n' Roll or anything. So finally I just hauled off and batted her with a drumstick, knocked her flat on her ass. Well, you better believe that got a reaction! They'd just been irritated before, now I think a lot of 'em would've liked to kill us. Wildwest buckskin vigilante scene, the Ox-Bow Incident in Griffith Park. Great theatre if they'd had the imagination. Instead they just flipped out and sorta ran us off the bandstand and outa the park for that Sunday. Wow! we said, Hmmm... so we started staging fights with each other while we were playing, except that after awhile you'd start to feel it and get pissed off for real and start throwing a little more weight behind the punches. We almost destroyed all our equipment several times. And we didn't really hold any grudges later because we'd worked 'em all off onstage and besides it was really blowing our minds what great reactions we were getting — they loved to see us get it on as long as we stuck to each other, because they hated our guts, and the harder we wailed on each other the more popular we got. But that was nothing to what happened when we started showing up in drag."

One thing led organic as Crunchy Granola to another, and one full moon the Cooper crew found themselves the center of a storm of even greater contention. Suddenly people stopped just disliking or even merely hating the band and began to talk about them in terms reserved for criminals against Karma, the Gilles de Rais of rock 'n' roll.

And all because of a few chickens.

The furor started innocently enough, as Alice patiently explained later: "One night in the middle of an outdoor show, one of the local chickens wandered onstage. I picked it up, and mistakenly assuming" — as any TV toddler from the tracts of Phoenix would — "that it could fly, I threw it in the air, and of course it just fell straight down and broke its neck. I flipped out. I picked up the carcass, I didn't know what else to do, and tossed it into the audience. Then we all flipped out, because they jumped on it screaming and tore it to pieces."

The next day he ran into Zappa, who told him he'd heard that Alice had beefed up the show the night before by grabbing a chicken, tearing its throat open with his teeth, and drinking its blood on the spot. Which just goes to show that where there's smoke there's some mighty wooly imaginations. (Another classic grisly R&R rumor had Lou Reed, when he disappeared from the Velvets and New York scene to parents' house in Long Island to think it out, so deranged from all the drugs his Legend-shadow had been taking that he spent all his time sitting in a bathtub dismembering Barbie dolls with a butcher knife!)

The chicken incident drove so many upstanding and even hipslouching folk prematurely apoplectic that a variation of it had to be worked into the act. But, again countering grapevine gospel, the band never killed the birds but threw live chickens into the audience to deal with as they saw fit. Which of course was irresponsible, but hardly constituted poultricide. Accessory. You can call it callous and despicable publicity gimmick, and in one sense it was, but it was also calculated as a way of forcing people to deal with their inner bloodlust and the close relationship it has always borne to what we all need and use rock 'n' roll for. And it earned them a truly vast scope of enemies in the counter culture.

It was in this period of escalating notoriety also that the band took to dressing up like broads. (Or ladies, as customary on Tuesday evenings; or Girl Scouts, Wednesday regulation; or Negro metermaids with watermelons stuffed in their uniforms for tits, Thursday — not even many died-in-the-worsted fans know that Alice instituted a strict regimen which called for precise costumes for each day of the week, to keep their imaginations juicy as Anita Bryant's oranges from the Florida Sunshine Tree and besides, who wants to be a deadbeat no'count old Broad every night ending up drunk and sorry as Tugboat Annie in her decline? No redblooded American youth, I can tell you!) And , just like Neal said, anybody who thought the reaction to the stage fights or the chickens was virulent just hadn't seen nuttin' yet.

Los Angeles is unarguably the crassest of the crass as towns go; it has a long history of unerring tastelessness, in the fumes that drop like viral manna from the sky and the slow rot of hosts of faded tinsel personalities. Nowadays, of course, it's in the forefront of the hip Decadence movement of which Unisex fashions are only the innocuous border. To slouch through the gutty innards of the Whiskey a Go Go today is to see whole sullen clots of people being so conscienciously decadent, fin-de-siecle and ostentatiously ennui-narcoleptic that it's ludicrous. It's not even a matter of gay or straight or bi for the most part, just a lot of deadheads shrouded in trendy threads and varying degrees of sexual indeterminacy, most of them without even the energy to be actively depraved. It's like all of them had their lives changed when Performance hit town and they saw Mick the Schtick mincing around in makeup and filmy robes, letting the word definitely out that the next big hipper-than-youse shift was on, except that this was one bandwagon that would finally separate the men from the boys (so to speak), 'cause it takes a certain amount of nerve to come on as effeminate as Mick Jagger if you're just a punk from Anaheim.

Bi is big this year (next year I think it's gonna be the old trick of fucking a chicken with a drawer just almost-closed on its head, so you slam the drawer, decapitate the fowl and enjoy the death-wriggles just when yer about to get yer gun — another instance, also, of the Alice Cooper Was There First syndrome), but in L.A. it seems to be mainly a fashion move, as 400 identical Rod Stewarts converge on the Whiskey every night trying to pick up the chicks, but are usually too fucked up to make the moves, so the chicks end up going home with some 37 year-old sculptor from Venice. In New York, I suspect, it's quite different — just as Women's Lib is most puissant there, that's where the sexual roles seem to have broken down or crossed and recrossed the most, and if the Whiskey is mainly known as a mere dive, who has not heard intimations of the dark doin's in The Back Room At Max's. Which shows once again just exactly where the power in the old U.S. of A. lies, decadence-wise. (Manhattan dresser-drawer chicken fuckers are advised to write — for sociological purposes only, of course).

But none of this had begun when Alice and his band started running onstage looking like something out of City of Night. In fact, few indeed were remotely ready for such a move. Alice: "It was great! We'd go on, and immediately you'd see ten thousand matches, like every guy in the house was nervously grabbing for a cigarette and lighting it. This happened again and again. Sometimes half the crowd would've walked out by halfway through the first song, but a lot of people were afraid to walk out. They were afraid to move, afraid I'd look at 'em and maybe say something. Do you realize what a sense of power that can give you?"

Times change fast, though; it's amazing the speed with which these titanic upheavals in Anglo-Saxon Attitudes piddle away to plain Ho Hummers. John Mendelsohn was right when he said that much of A.C.'s audience is running neck and neck with them in the race to out-outrageous the next clown, if not way ahead of befits a brannew generation, and the id-shrapnelling routines of just a year or two ago stand in serious danger of relegation to the Old Hat box.

Alice Cooper purports to deal with sex, but that is extremely debatable. They've only delt with it on the most superficial, readymade level: that whole androgynous-seduction-of-the-audience riff, which is getting so fucking corny it's putting everybody to sleep. Jagger still does it better than anybody else around (and even on him it's wearing mighty thin), Morrison turned it into burlesque (in the comic sense), and Iggy drove a stake straight through its heart. Somebody is going to have to think of something new; it sure ain't Mark Farner, and it ain't Rod Stewart (though he comes the closest), and it ain't Alice Cooper so far. Alice has nothing in common with Elvis, Jagger and Morrison, which means he's not the stuff of which sex idols are made, unless Bugs Bunny is a sex idol.

Another problem, and one that Alice and band have not confronted at all, is that to deal really honestly with sex in America today, you've got to deal with the problem of isolation. It really doesn't make much difference in this light whether we're talking about "straight," "gay," "promiscuous," or celibate. The one constant is the incredible difficulty so very many people have in truly getting outside of themselves and into another person in a significant way. And so far only a small number of rock 'n' roll songwriters have even begun to tackle that crucial subject maturely. For all the "soul-searching" songwriting going on now almost nobody has managed to come up with anything on the subject of sex substantially beyond such rusty warhorses as unrequited subjecting, vindictive resentment, narcissified conceits, couplings of sexual potency with quasi-political movements a la the Jefferson Airplane, etc. Which is really sad, because songs dealing intelligently with sexual nuance can be written, and some already have: Ray Davies' "Lola" is probably the funniest, although Lou Reed's "Some Kinda Love" is a classic, along with his great adultery song "Pale Blue Eyes," and "Candy Says," which says more, and more concisely, about the pangs of American adolescence than any other song remembered from the past 5 years. And the all-time model is still the Stones' "Sittin' On a Fence," which practically summarized every marriage I saw undertaken in its era.

I would like to see Alice, like the Stones, Davies and Reed, get into writing more about real sexual situations, from whatever vein of experience. "Long Way To Go", after all, says a lot more about sex now than "Is It My Body," and if "Eighteen" is any indication he could probably delineate adolescent horniness as sharply as Iggy or the MC5 ever did, and more hilariously to boot.

Then again, maybe that's not his job. It may just be that Alice's Cooper's job is the twofold talk of becoming one of the finest, if not the Number One Third Generation rock band extant, and transmuting and refining all that crass culture we picked up our lives long from cartoons, TV and movies into and through that music. The first purpose comes closer to full realization all the time, and as for the second, well, the boys are studying, soaking up the ersatz media they intend to blitz us with. They owned a farm in Pontiac, Michigan for the time, and I came to learn that if you had just finished watching a really crass movie on the tube, movies like Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter and Reform School Girl, no matter what time of the day it was you could call up Alice if they weren't on tour and, sure enough, he'd just finished watching it too. He soaks all of that stuff up, every drop, and builds it one way or another into one of his numerous roles.

When I went to their farm I found the rest of the band out by the fence with their brand-new air rifles, shooting at beer bottles and hooting like Okies even if they did still have slight traces of makeup on from the previous night's show. When I went in the house I expected to see Alice reading a copy of The American Rifleman, but instead I found him in an overstuffed easy chair, guzzling Budweiser and watching an old movie called Dillinger with much glee. As he finished each can he would hurl it to the floor, amidst the dozens of empties scattered around, and whine to Cindy: "Blondie! Blondieee! Bring me my beeeer!"

Later we all went outside for a baseball game on the lower forty. It was a nipping cold day, and some folks, notwithstanding the fact that they were hippies who hadn't had a bat in their hands in maybe 5 or 10 years, played a downright desultory game, seemingly thinking only of getting back in by the fire with TV and a bottle of wine. But Alice, playing outfield, ran with unerring intentness from one end of his section of the pasture to the other, and caught every single fly that came his way.

Later I mentioned to Cindy that "Alice must have a really strong personality."

"Yes," she said. "Three or four of them."