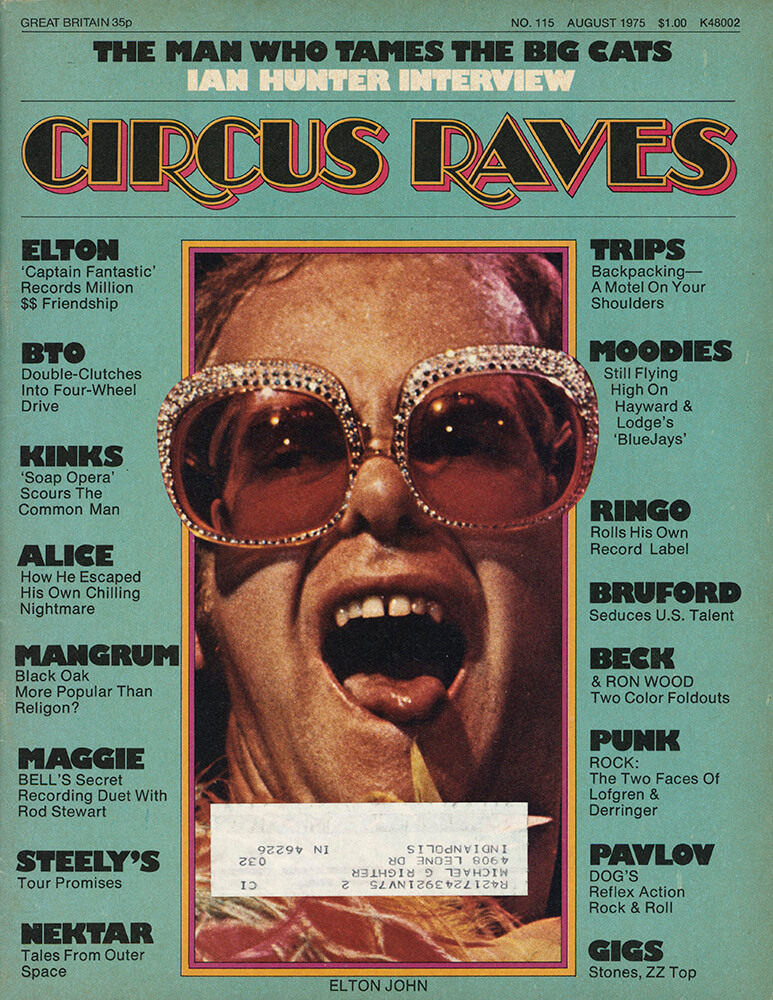

Article Database

Circus Raves

August 1975

Alice Escapes From His Own Nightmare

Author: Ron Ross

On a rare day off in the midst of his marathon 68-city "Welcome To My Nightmare" tour of America, Alice Cooper is lounging on the terrace of his Tampa hotel suite. Though his bedroom offers a palmy riverfront view, the Coop has wheeled his color TV onto the veranda and keeps his back to the scenery while he sips a 16-ounce Budweiser and halfwatches "Star Trek." Alice hadn't gotten much sleep the night before, after his concert in Atlanta, but it wasn't his notorious nightmares that kept him awake; Alice was under a far more powerful influence to insomnia: golf fever. The shock rock king, now rather unshockingly attired in coral colored Gatsby slacks and a splashy Hawaiian shirt, couldn't bear the thought of giving up even a single day on the links, when his private plane could take him to sunny Florida in time to hit the course first thing in the morning.

So the entire Cooper entourage of 40 people, including five musicians, four dancers, and his guest star, Suzi Quatro's band, had boarded the "Nightmare I," as the plane came to be called, at 3 A.M., flew through a thunderstorm, and checked into yet another hotel at the crack of dawn to accommodate the sporting superstar. Though Alice himself had only rested a couple of hours, it was all worth it once he was on the green. Pointing out a sink full of Bud, and saying, "help yourself," Alice admits, "It sounds so silly for me to come home and brag about shooting an 84, but I haven't played for two months because of our 16 hour a day rehearsal schedule. Every time we fly over a city, I look down for golf courses. I get excited at the mere thought of driving and putting; that's my personal release."

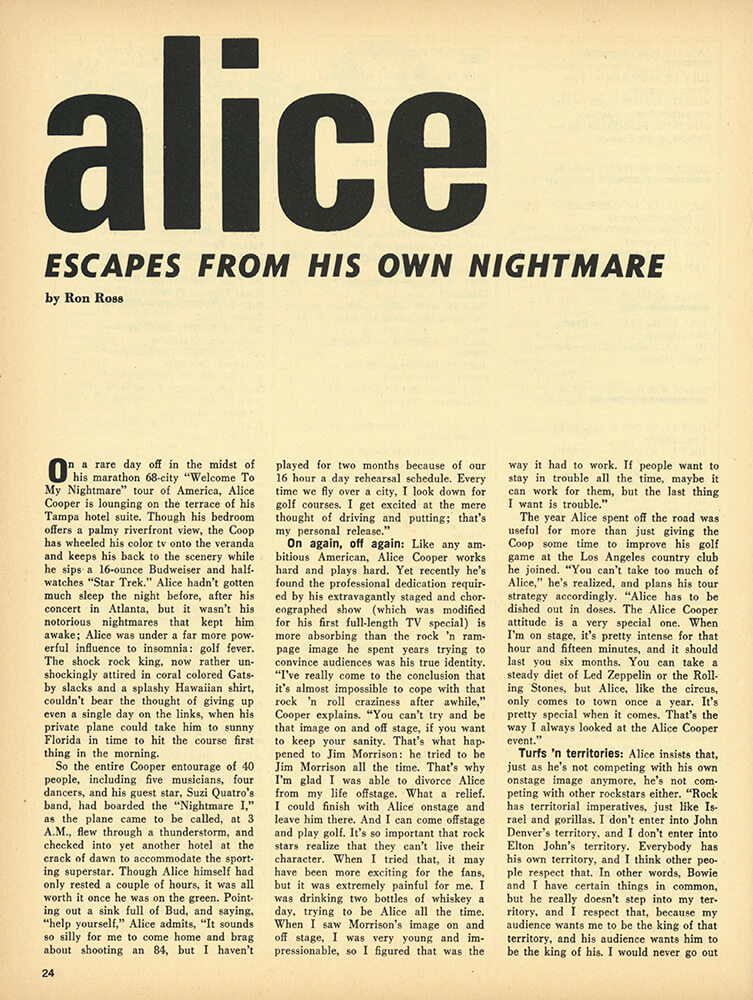

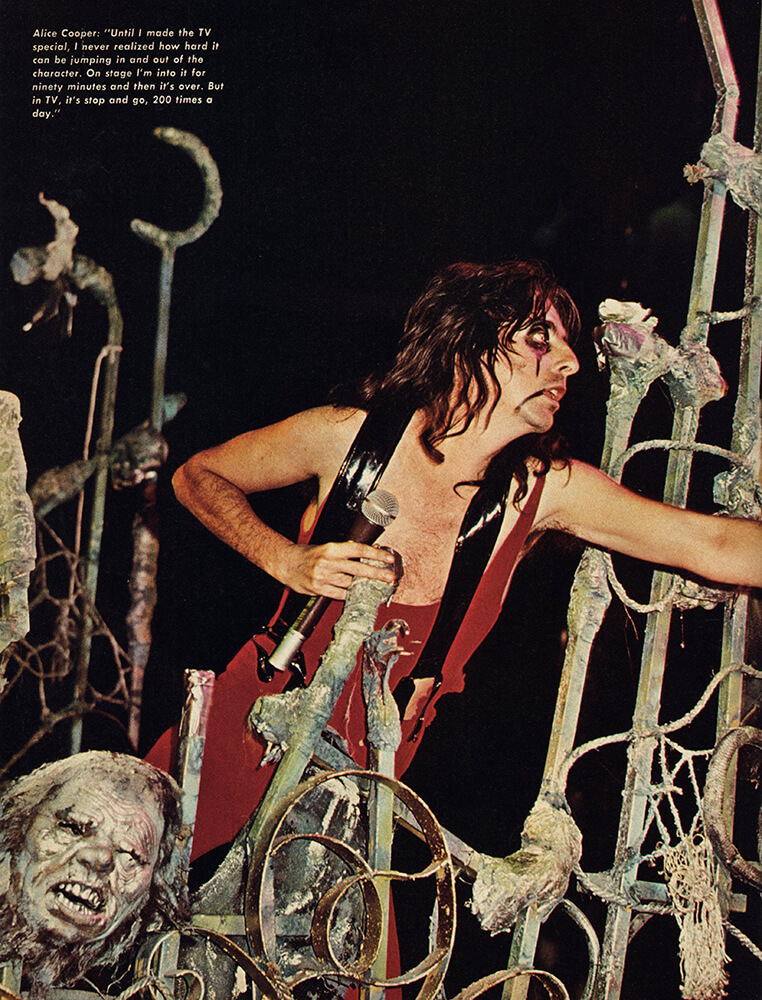

On again, off again: Like any ambitious American, Alice Cooper works hard and plays hard. Yet recently he's found the professional dedication required by his extravagantly staged and choreographed show (which was modified for his first full-length TV special) is more absorbing than the rock 'n rampage image he spent years trying to convince audiences was his true identity. "I've really come to the conclusion that it's almost impossible to cope with that rock 'n roll craziness after awhile," Cooper explains. "You can't try and be that image on and off stage, if you want to keep your sanity. That's what happened to Jim Morrison: he tried to be Jim Morrison all the time. That's why I'm glad I was able to divorce Alice from my life offstage. What a relief. I could finish with Alice onstage and leave him there. And I can come offstage and play golf. It's so important that rock stars realize that they can't live their character. When I tried that, it may have been more exciting for the fans, but it was extremely painful for me. I was drinking two bottles of whiskey a day, trying to be Alice all the time. When I saw Morrison's image on and off stage, I was very young and impressionable, so I figured that was the way it had to work. If people want to stay in trouble all the time, maybe it can work for them, but the last thing I want is trouble."

The year Alice spent off the road was useful for more than just giving the Coop some time to improve his golf game at the Los Angeles country club he joined. "You can't take too much of Alice," he's realized, and plans his tour strategy accordingly. "Alice has to be dished out in doses. The Alice Cooper attitude is a very special one. When I'm on stage, it's pretty intense for that hour and fifteen minutes, and it should last you six months. You can take a steady diet of Led Zeppelin or the Rolling Stones, but Alice, like the circus, only comes to town once a year. It's pretty special when it comes. That's the way I always looked at the Alice Cooper event."

Turfs 'n territories: Alice insists that, just as he's not competing with his own onstage image anymore, he's not competing with other rockstars either. "Rock has territorial imperatives, just like Israel and gorillas. I don't enter into John Denver's territory, and I don't enter into Elton John's territory. Everybody has his own territory, and I think other people respect that. In other words, Bowie and I have certain things in common, but he really doesn't step into my territory, and I respect that, because my audience wants me to be the king of that territory, and his audience wants him to be the king of his. I would never go out onstage and try to take the Carpenters' audience, 'cause if they came to see my show, they'll realize that I'm not trying to compete."

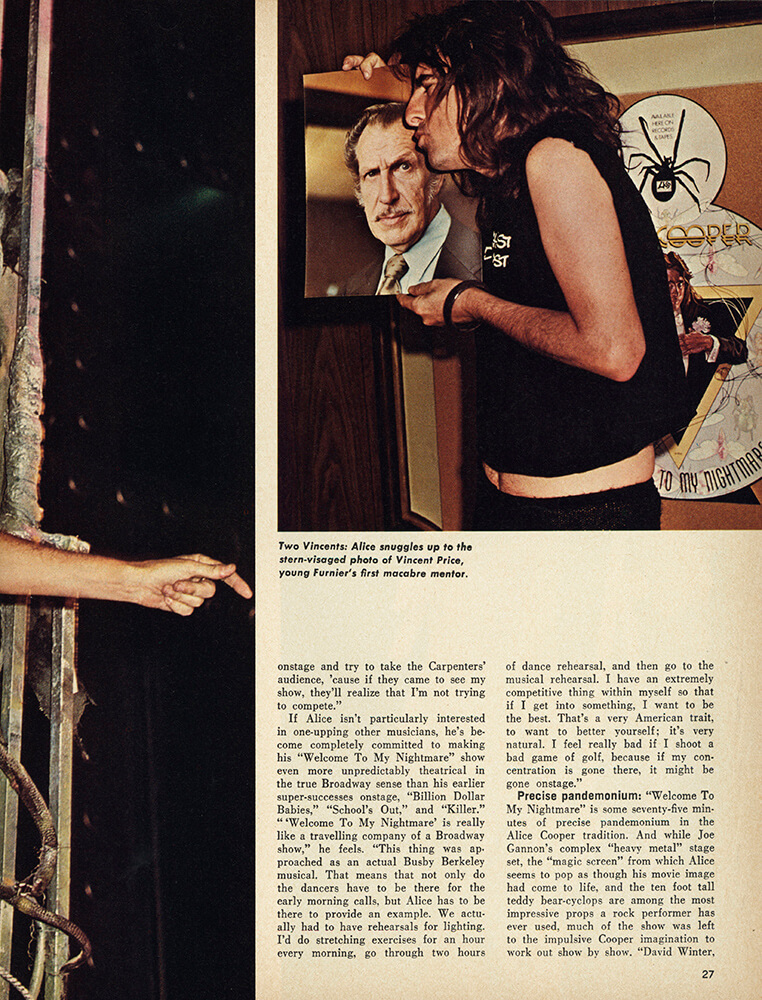

If Alice isn't particularly interested in one-upping other musicians, he's become completely committed to making his "Welcome To My Nightmare" show even more unpredictably theatrical in the true Broadway sense than his earlier super-successes onstage, "Billion Dollar Babies," "School's Out," and "Killer." "'Welcome To My Nightmare' is really like a travelling company of a Broadway show," he feels. "This thing was approached as an actual Busby Berkeley musical. That means that not only do the dancers have to be there for the early morning calls, but Alice has to be there to provide an example. We actually had to have rehearsals for lighting. I'd do stretching exercises for an hour every morning, go through two hours of dance rehearsal, and then go to the musical rehearsal. I have an extremely competitive thing within myself so that if I get into something, I want to be the best. That's a very American trait, to want to better yourself; it's very natural. I feel really bad if I shoot a bad game of golf, because if my concentration is gone there, it might be gone onstage."

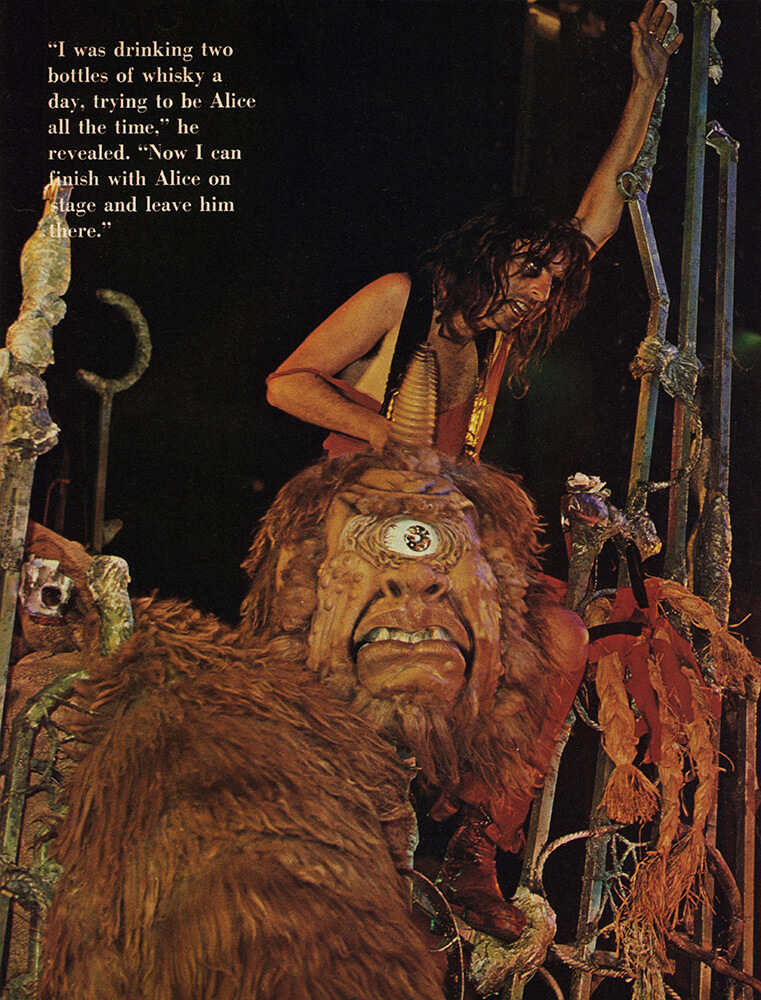

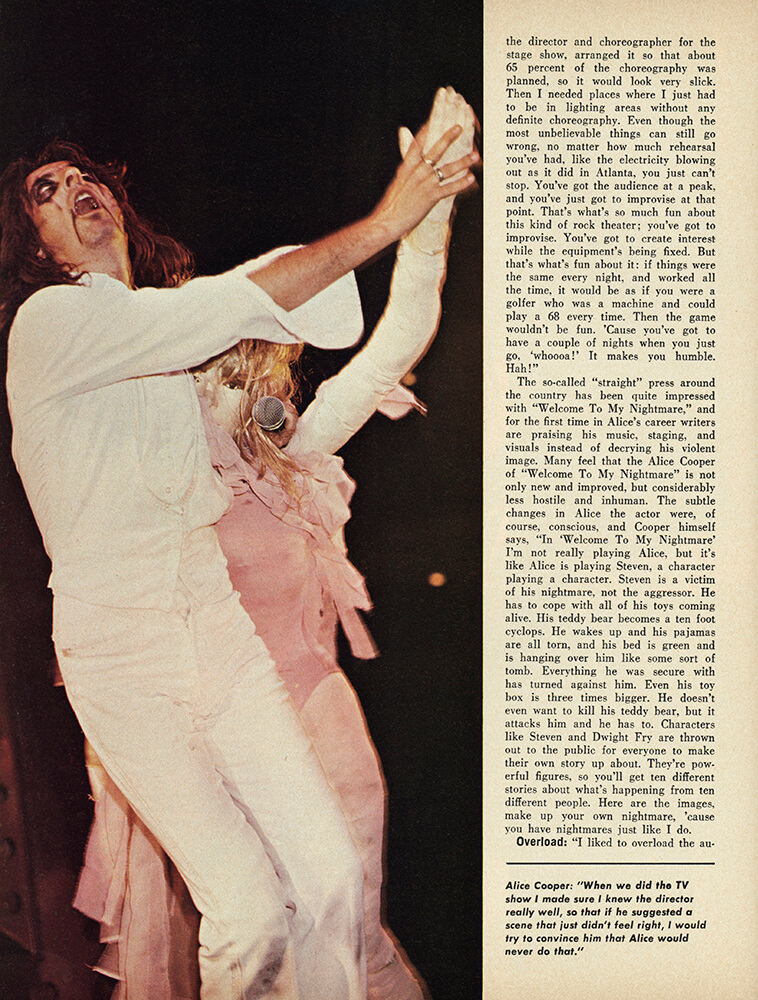

Precise pandemonium: "Welcome To My Nightmare" is some seventy-five minutes of precise pandemonium in the Alice Cooper tradition. And while Joe Gannon's complex "heavy metal" stage set, the "magic screen" from which Alice seems to pop as though his movie image had come to life, and the ten foot tall teddy bear-cyclops are among the most impressive props a rock performer has ever used, much of the show was left to the impulsive Cooper imagination to work out show by show. "David Winter, the director and choreographer for the stage show, arranged it so that about 65 percent of the choreography was planned, so it would look very slick. Then I needed places where I just had to be in lighting areas without any definite choreography. Even though the most unbelievable things can still go wrong, no matter how much rehearsal you've had, like the electricity blowing out as it did in Atlanta, you just can't stop. You've got the audience at a peak, and you've just got to improvise at that point. That's what's so much fun about this kind of rock theater; you've got to improvise. You've got to create interest while the equipment's being fixed. But that's what's fun about it: if things were the same every night, and worked all the time, it would be as if you were a golfer who was a machine and could play a 68 every time. Then the game wouldn't be fun. 'Cause you've got to have a couple of nights when you just go, 'whoooa!' It makes you humble. Hah!"

The so-called "straight" press around the country has been quite impressed with "Welcome To My Nightmare," and for the first time in Alice's career writers are praising his music, staging, and visuals instead of decrying his violent image. Many feel that the Alice Cooper of "Welcome To My Nightmare" is not only new and improved, but considerably less hostile and inhuman. The subtle changes in Alice the actor were, of course, conscious, and Cooper himself says, "In 'Welcome To My Nightmare' I'm not really playing Alice, but it's like Alice is playing Steven, a character playing a character. Steven is a victim of his nightmare, not the aggressor. He has to cope with all of his toys coming alive. His teddy bear becomes a ten foot cyclops. He wakes up and his pajamas are all torn, and his bed is green and is hanging over him like some sort of tomb. Everything he was secure with has turned against him. Even his toy box is three times bigger. He doesn't even want to kill his teddy bear, but it attacks him and he has to. Characters like Steven and Dwight Fry are thrown out to the public for everyone to make their own story up about. They're powerful figures, so you'll get ten different stories about what's happening from ten different people. Here are the images, make up your own nightmare, 'cause you have nightmares just like I do.

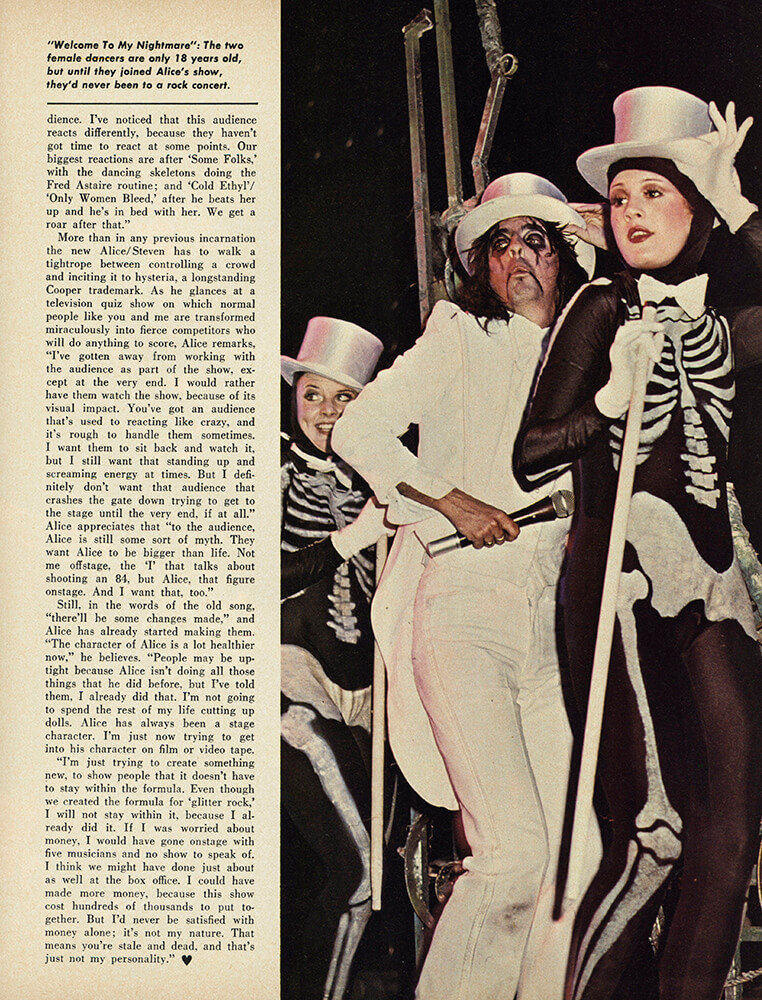

Overload: "I liked to overload the audience. I've noticed that this audience reacts differently, because they haven't got time to react at some points. Our biggest reactions are after 'Some Folks,' with the dancing skeletons doing the Fred Astaire routine; and 'Cold Ethyl'/'Only Women Bleed,' after he beats her up and he's in bed with her. We get a roar after that."

More than in any previous incarnation the new Alice/Steven has to walk a tightrope between controlling a crowd and inciting it to hysteria, a longstanding Cooper trademark. As he glances at a television quiz show on which normal people like you and me are transformed miraculously into fierce competitors who will do anything to score, Alice remarks, "I've gotten away from working with the audience as part of the show, except at the very end. I would rather have them watch the show, because of its visual impact. You've got an audience that's used to reacting like crazy, and it's rough to handle them sometimes. I want them to sit back and watch it, but I still want that standing up and screaming energy at times. But I definitely don't want that audience that crashes the gate down trying to get to the stage until the very end, if at all." Alice appreciates that "to the audience, Alice is still some sort of myth. They want Alice to be bigger than life. Not me off stage, the 'I' that talks about shooting an 84, but Alice, that figure onstage. And I want that, too."

Still, in the words of the old song, "there'll be some changes made," and Alice has already started making them. "The character of Alice is a lot healthier now," he believes. "People may be uptight because Alice isn't doing all those things that he did before, but I've told them, I already did that. I'm not going to spend the rest of my life cutting up dolls. Alice has always been a stage character. I'm just now trying to get into his character on film or video tape.

"I'm just trying to create something new, to show people that it doesn't have to stay within the formula. Even though we created the formula for 'glitter rock,' I will not stay within it, because I already did it. If I was worried about money, I would have gone onstage with five musicians and no show to speak of. I think we might have done just about as well at the box office. I could have made more money, because this show cost hundreds of thousands to put together. But I'd never be satisfied with money alone; it's not my nature. That means you're stale and dead, and that's just not my personality."