Article Database

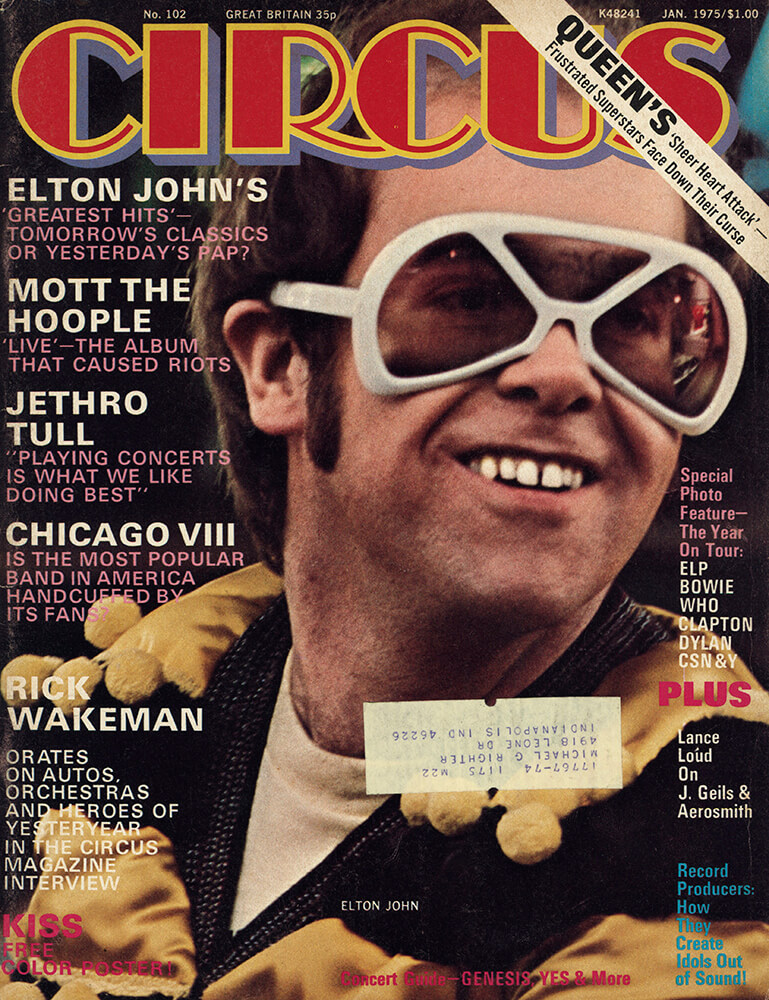

Circus

January 1975

The Record Producers: How They Create Idols of Sound

They say Orpheus sang so sweetly he was torn apart by wanton women, but no one will everknow the famous warbler's secret — there were no record producers in ancient Greece.

Author: Joe Bivona

With his pipe clenched solidly between his teeth, a serious faced gentleman gave the signal to his engineer that started the Record Plant's massive tape machines rolling. In a flash, what seemed to be a dozen arms started twisting knobs and pulling switches on the Record Plant's huge, sixteen-track control board, laying down the final mix of a cut from Lou Reed's Berlin album. Up came the fade out, and the man settled back, slapped his engineer five, and told him to "wrap up this turkey before I puke."

The man's name was Bob Ezrin, and while not a rock star in the usual sense of the word, he's responsible for a big part of what you hear when you play records by Reed, Aerosmith and especially Alice Cooper — he is their producer.

Now more than ever, the producer shares much of the credit for the way a particular album sounds. Noted rock music critic Dave Marsh in reviewing an album by David Baretto put this feeling in sharp perspective when he wrote, "It's hard to say whether the true star of this album is Baretto... or his producer, Shadow Mortori." Going on to enumerate Shadow's influences on the album, Marsh underscored the high level of responsibility the producer takes on when he does an album.

The producer invariably handles his job on an elaborate control board, usually assisted by an engineer. After the band has laid down their 8, 12, or 16 separate tracks of tape, it's the producer's job to "mix" the separate tracks (combine them at proper relative volume levels), place them (position each instrument so it appears to be coming from somewhere between your stereo speakers), and preside over the mixdown, the process of merging the numerous individual tracks of tapes into two track stereo. Most special effects that are heard in an album — guitars whizzing back and forth between the speakers and the like — also come from the producer fiddling with the control knobs. It's no wonder, then, that a band will choose their producer with the care usually reserved for another band member.

Out of the shadows: It hasn't always been that way, though. Before the advent of the behemoth 16-track tape machines and wall-to-wall control boards the producer's job was relatively simple. As the band played together, the engineer would monitor the volume levels of the studio microphones and control board inputs, and after picking up the band on either two, three, or four tracks of tape, the producer would simply mix them down to one-track mono. Whatever the band played is what the listener got; the producer just served as a stepping stone from the studio to the wax.

One man had a different idea, though, and he single handedly changed the producer's role for all those who came after him. His name was Phil Spector.

The Wall of Sound: Spector's idea of selling records was unique. Up until the late fifties, a record sold on the popularity of the group or the catchiness of a particular song; but what mattered most to Spector was the "sound" quality the performers had. Working with the Teddy Bears in 1958, Spector first unleashed what came to be known as the "wall of sound" in a song called "To Know Him Is To Love Him." Lushly textured, choir-like vocal harmonies replaced the dull, flat "shoobop-de-doo-wop" of other recordings of that era, while thick orchestral arrangements rode on top of heavily echoed guitar, bass, and drums. The background sounds added a whole new dimension and depth to the song and the result was awe-inspiring. It was truly the sound heard 'round the world, and soon the Shirelles, the Ronettes and the Righteous Brothers joined the Teddy Bears at the top of the charts.

While those golden names might not sound all that familiar to those under 20, Spector's influence can also be heard on many later albums, and his production work on the Beatles' Let It Be album was a factor in holding that band together a little longer. John Lennon recalls, "Nobody could face looking at it [Let It Be]. So when Spector came around, you know, all right, if you want to work with us, go and do your audition." And he did.

Spector took the 29 hours of rough tape and transformed it into one of the Beatles' best loved albums — all made possible by Phil Spector's deft hands on the control board.

Chairmen of the Board: Around the time that Spector started making waves, a second big development helped change the role of the record producer — the concept of multi-track recording.

Instead of having to record all the instruments and voices concurrently on one track of tape, each instrument or group of instruments could be allotted its own separate track. This allowed such innovative maneuvers as overdubbing — recording an instrument or voice to a song after the basic rhythm tracks had been laid down. The result was a much "cleaner" sound, and producers started to take advantage of the many mixing possibilities that multi-track recording made possible. As the need for more flexibility arose, larger and more complicated 8 and 16 track machines came into use. With the potential for creating an infinite variety of new and unique sounds available, their execution was bound only by the limits of the producer's imagination.

The control board, the producer's link from the band in the studio to the tape machines, also went through its evolution. Originating as a mild-mannered mixing panel housing little more than volume and tone controls and some switches, the modern control board is a far cry from its ancestors. Sometimes spanning the width of the control room, the modern board can handle the recording of an entire orchestra in one fell swoop, is able to harness the heaviest rock bands in a single stereo mix, and affords the producer a creative versatility far beyond his normal needs. 36 or more identical rows of knobs and switches run the width of the board while the remaining space is taken up by assorted equalizers, dolby systems, monitors, patch boards, V.U. meters and master controls. If it sounds complicated, it is. But in the hands of a competent producer, the control has been instrumental in producing some minor miracles over the past few years.

One of the unlikeliest miracles came out of the meeting between a skinny runt from Philadelphia and a superband on the verge of collapse.

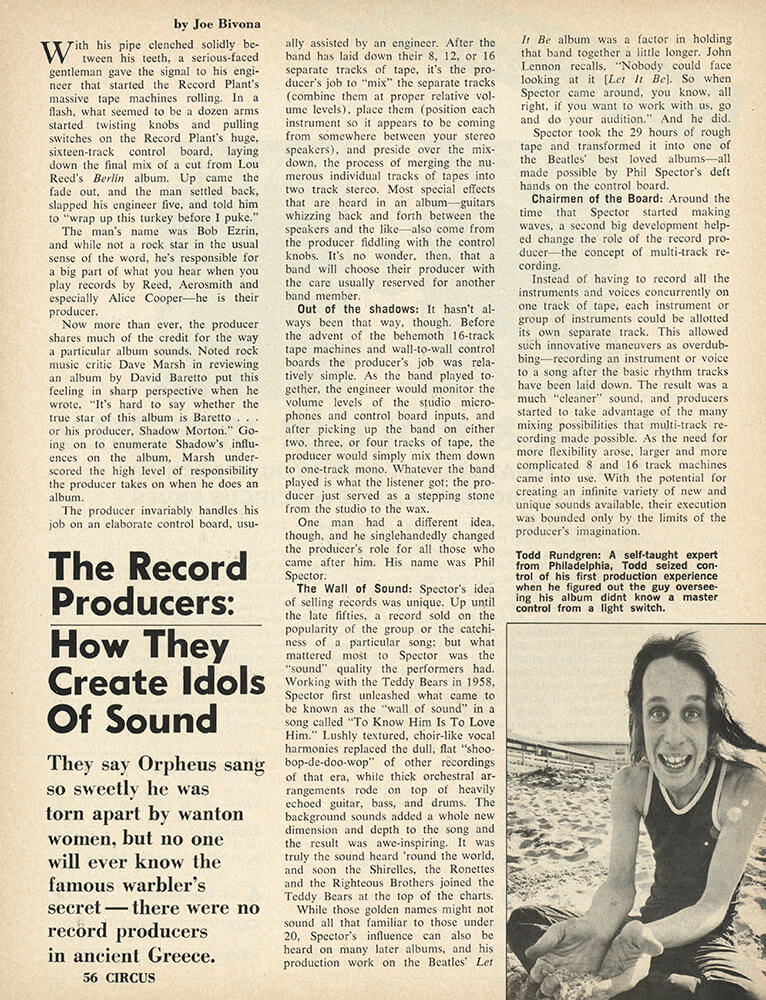

Re-railing the Railroad: In any conversation where the phrases "producing whiz", or "boy genius" are used, references will usually be made to rainbow haired Todd Rundgren. More renowned as a producer than as a solo artist, Rundgren first tried his hand at producing with a group of fellow Philadelphians, the American Dream under the guidance of Albert Grossman, Bob Dylan's manager. Gradually piling up experience behind the control board with artists like the Band, Jesse Winchester, Janis Joplin and Paul Butterfield, "the Kid" (as Todd is known to his fans) was soon faced with a production challenge of immense proportions — Grand Funk.

The meeting between Grand Funk and Todd was suggested by Funk's manager, Andy Cavaliere, for good reason. Phoenix, their latest album which they'd produced themselves, wasn't selling well with the public. Lacking the publicity push formerly provided by Terry Knight, things looked dismal for the Michigan-based band, with every critic and his dog jumping on the bury-Funk bandwagon. Drummer Don Brewer recalls, "There were times when we wondered if we were going to make it on our own." Enter Todd Rundgren.

Hustling Grand Funk into Miami's Criteria Studios, Rundgren carefully mapped out plans designed to bring out the best Funk had to offer. "The whole point of my work with them was to validate them as artists," said Rundgren later. "That was the prime consideration from the very beginning."

Settling down to work, Todd constructed a totally new sound for the ailing Railroad. Taking the place of Terry Knight's empty base-drums-guitar sound was a rich textured sound augmented by the addition of Craig Frost on organ. Mark's slightly pale vocals were given an extra boost by the kid fiddling with the knobs. When "We're an American Band" hit the racks, it had critics and fans alike jubilant — "The best album Grand Funk has ever done," said more than one record receiver. Even Funk's former producer, Terry Knight himself, admitted Todd's solution to the group's sound problems was brilliant. "Grand Funk have always been deficient as musicians and never pretended not to be," he opined. "I think Todd did exactly what they needed to appeal to that mass AM radio audience that they'd always missed before. Todd hid all Grand Funk's deficiencies with a blanket of echo, if you listen to it carefully, which is exactly what I wouldn't do when I was the producer. You can hide a city in an incredible blanket of smog and never see the dog-crap beneath it on the sidewalks."

As the praise continued to pile on the reborn Funk, it became apparent to many that the producer, so often taken for granted, could be taken for granted no longer.

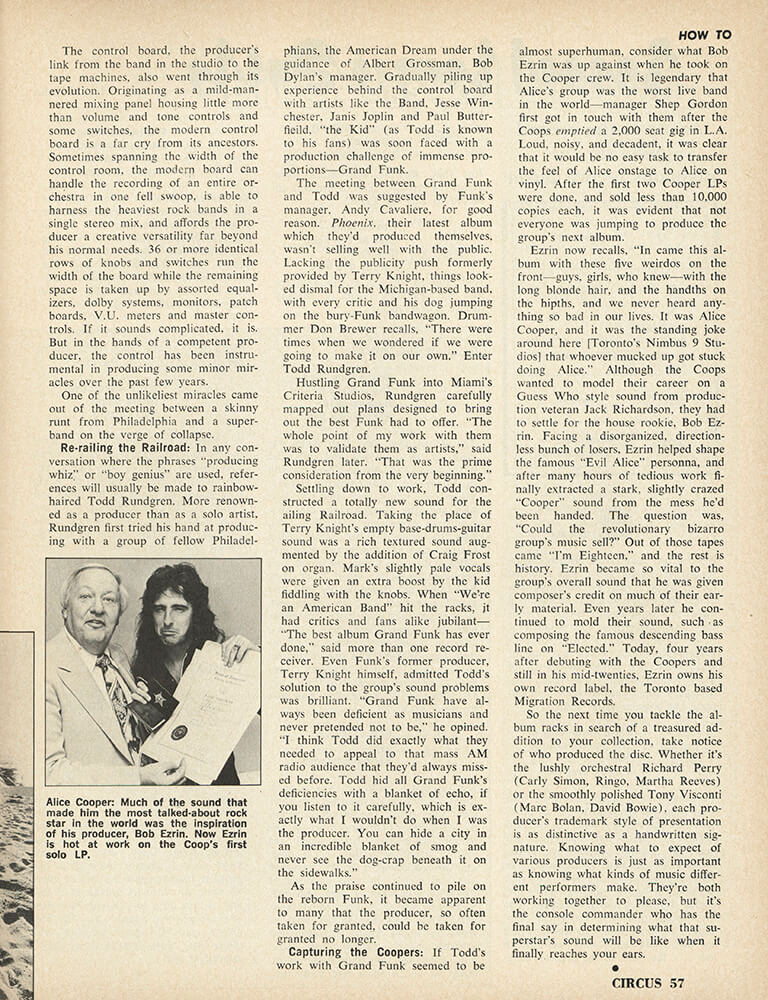

Capturing the Coopers: If Todd's work with Grand Funk seemed to be almost superhuman, consider what Bob Ezrin was up against when he took on the Cooper crew. It is legendary that Alice's group was the worst live band in the world — manager Shep Gordon first got in touch with them after the Coops emptied a 2,000 seat gig in L.A. Loud, noisy, and decadent, it was clear that it would be no easy task to transfer the feel of Alice onstage to Alice on vinyl. After the first two Cooper LPs were done, and sold less than 10,000 copies each, it was evident that not everyone was jumping to produce the group's next album.

Ezrin now recalls, "In came this album with these five weirdo front — guys, girls, who knew — with the long blonde hair, and the handths on the hipths, and we never heard anything so bad in our lives. It was Alice Cooper, and it was the standing joke around here [Toronto's Nimbus 9 Studios] that whoever mucked up got stuck doing Alice." Although the Coops wanted to model their career on a Guess Who style sound from production veteran Jack Richardson, they had to settle for the house rookie, Bob Ezrin. Facing a disorganized, directionless bunch of losers, Ezrin helped shape the famous "Evil Alice" persona, and after many hours of tedious work finally extracted a stark, slightly crazed "Cooper" sound from the mess he'd been handed. The question was, "Could the revolutionary bizarro group's music sell?" Out of those tapes came "I'm Eighteen," and the rest is history. Ezrin became so vital to the group's overall sound that he was given composer's credit on much of their early material. Even years later he continued to mold their sound, such as composing the famous descending bass line on "Elected." Today, four years after debuting with the Coopers and still in his mid-twenties, Ezrin owns his own record label, the Toronto based Migration Records.

So the next time you tackle the album racks in search of a treasured addition to your collection, take notice of who produced the disc. Whether it's the lushly orchestral Richard Perry (Carly Simon, Ringo, Martha Reeves) or the smoothly polished Tony Visconti (Marc Bolan, David Bowie), each producer's trademark style of presentation is as distinctive as a handwritten signature. Knowing what to expect of various producers is just as important as knowing what kinds of music different performers make. They're both working together to please, but it's the console commander who has the final say in determining what that superstar's sound will be like when it finally reaches your ears.

Cooper Golf To Glory In Nashville

After a ceremony during which he was dubbed an Honorary Deputy Sheriff of Davidson County, Tennessee, Alice Cooper went on to place fourth with his team-mates in Nashville's Tenth Annual Music City Pro Celebrity Golf Tournament. Personalities like Alice, Flip Wilson, Mickey Mantle, Pat Boone, Whitey Ford, Dale Robertson, Perry Como, and Chet Atkins formed foursomes with nationally successful pro golfers and "country gentlemen," including some of Nashville's most prominent music people, to compete for charity. Alice's sterling squadron was comprised of top-five rated pro Frank Beard, STP motor product prexy John Jay Hooker, and music publisher Joe Johnson, who duffed their way around the course for the event's largest crowd ever.

While attending a party at the Governor's Mansion, Alice mentioned how pleased he was to have been listed as Vince Furnier in the 1974-1975 edition of the prestigious reference work "Who's Who in America." "I think it's great," Cooper crowed, "because 'Who's who' is an American institution, and I believe in anything that is an American institution such as Hugh Hefner, Walt Disney, the Boy Scouts and Budweiser." Alice was then off to Toronto to finish work on his first solo album, which does not feature any of the other Coopers, but which does sound firstrate due to the production talents of Bob Ezrin and the great guitar of exReed rock and roll animal Dick Wagner.