Article Database

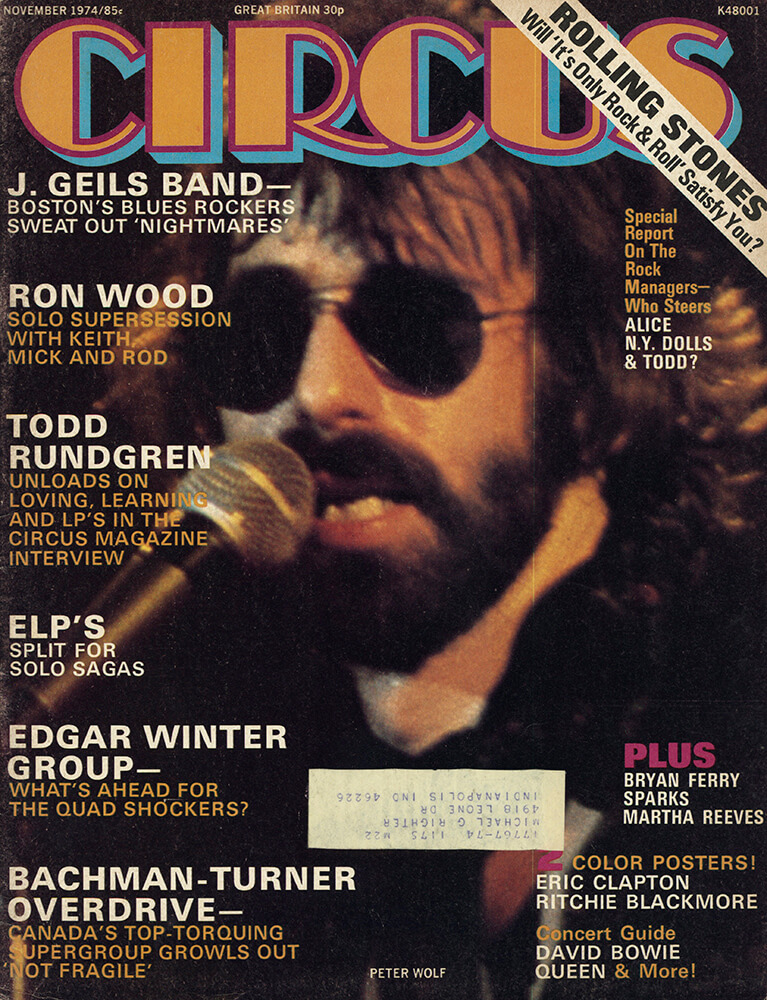

Circus

November 1974

The Rock Managers — Who Steers The Stars?

The rock and roll stars may shine brightly, but some creator's hand has to keep them spinning through space. Circus Magazine talks to the men the stars' lives depend on.

Author: R. Couri Hay

He's seen this rock and roll act more often than anyone in the world. Pacing just outside the glare of the spotlights, he's one of the most essential members of the group, yet he's never seen onstage. A combination mother hen and shark-hearted businessman, the rock manager is the star's star, the man the boys in the band run to when problems arise. Being a manager isn't all glamor, parties, gigs and limousines — but almost. To get some idea of the life of a manager, his work and his clients, Circus Magazine talked to the cream of the industry's platter potentates.

Basically the manager is concerned with the day to day living and working of his star; he's the closest member of the party outside the group, and his responsibility is heavy. He makes sure an artist gets all his royalties, that his record contract is fulfilled down to the last sub-clause, and that when the act goes out on the road it's promoted correctly, especially when a new album is out. The manager also decides how his artist's image is being affected by the media, setting up interviews and public appearances. He acts as an objective mirror, reminding an artist of what he's forgetting ('Hey, Ritchie, you did not play "Smoke On The Water" yet'), or advising him on song selections for particular audiences.

Equally as important, though the manager must keep his act in fighting trim psychologically. He acts as an interceptor and buffer against business hassles and negative vibes. He provides the right ego massage when it's necessary, and the right cash when that's necessary. In the case of a rich band this may extend to obtaining the right rare wine for his hotshot lead guitarist when they're passing through Kalamazoo. With more fledgling bands, the manager's babysitting function may extend to paying food and electric bills for the musicians. When you're managing rock and roll artists, their lives are in your hands.

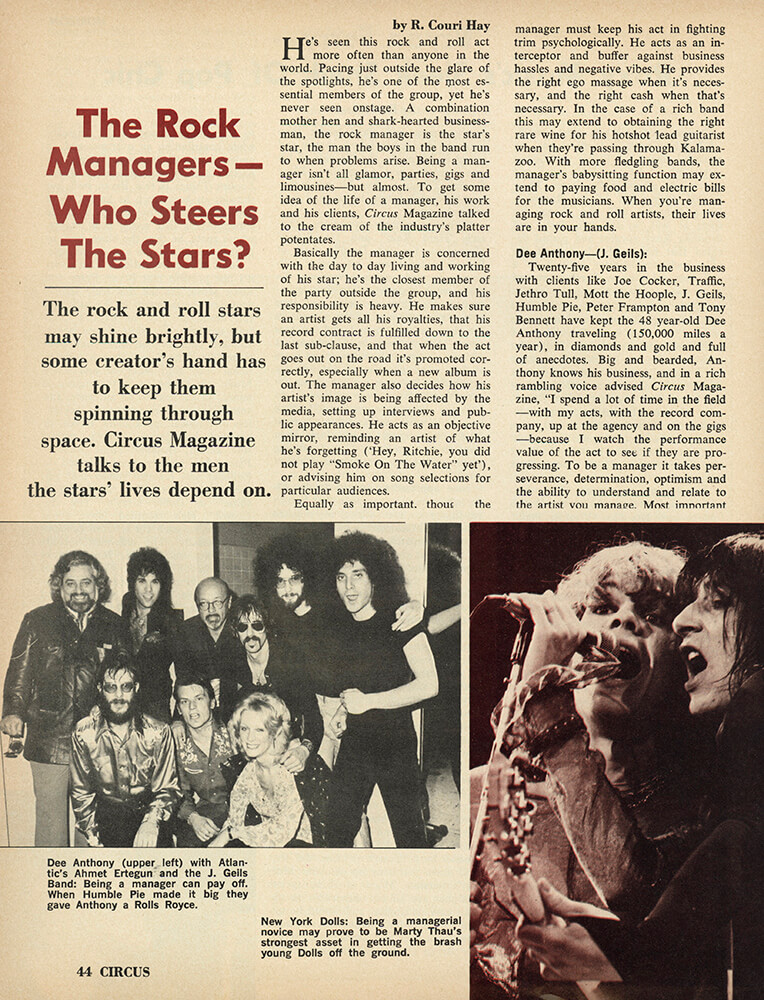

Dee Anthony — (J. Geils):

Twenty-five years in the business with clients like Joe Cocker, Traffic, Jethro Tull, Mott the Hoople, J. Geils, Humble Pie, Peter Frampton and Tony Bennett have kept the 48 year-old Dee Anthony traveling (150,000 miles a year), in diamonds and gold and full of anecdotes. Big and bearded, Anthony knows his business, and in a rich rambling voice advised Circus Magazine, "I spend a lot of time in the field — with my acts, with the record company, up at the agency and on the gigs — because I watch the performance value of the act to see if they are progressing. To be a manager it takes perseverance, determination, optimism and the ability to understand and relate to the artist you manage. Most important is to instill confidence in them to go beyond what they think their limitations are and make them go with their own convictions. Basically artists are very insecure, very frightened about where they are going to be from one day to another, if they're going to make it or not. You have to give them the self-assurance that their talent can override anything."

Anthony feels like 28 and relates to his 18 year-old daughter, who worked at his office this summer, like a brother would. Over a period of years he has suffered a lot of knocks and has come out stronger than ever. "This business has its cut-throats. There are schemers who wake up every day and expend all their energies in wheeling and dealing. I wake up every day and expend all my energies in advising and counselling my acts and seeing what I can do to make them progressively better for their career."

Dee pointed out that success has ruined many careers as well as nurtured them. "I wish I could give you all the answers to Joe Cocker, for instance. In all due respect, I think my office did a masterful job with Joe, but he flaked, he went out on us. He didn't want to go out on the road anymore, and when he did go out he had a change of heart about what he wanted to do. It's a shame because I love Joe. I even spoke to him as recently as two months ago, before he went out and did that comeback show at the Roxy in L.A., which didn't work out. I wasn't managing him, but I saw him out on the Coast and I said, 'Joe, it's a good shot for you. It's all waiting there for you, there is your audience, just lay it on them.' I'd heard his album and it's fantastic. Now what complexities or complications are going through his mind, I don't know.

"Maybe he reaches a certain height and then is frightened to go beyond that," Dee added. "He might have a very strong self-destructive mechanism going inside him. Some artists like to destroy and set up again, destroy and set up again. Some destroy to get new challenges and some destroy because they are frightened. With Joe it's a combination of things. We had him up to $50,000 a night. When he didn't come out on the road, we had over two and a half million dollars worth of bookings waiting for him to do which we lost. He had worked so hard to get there. After 25 years I still don't know the answers to a lot of things. What makes an act all of a sudden say 'No'?"

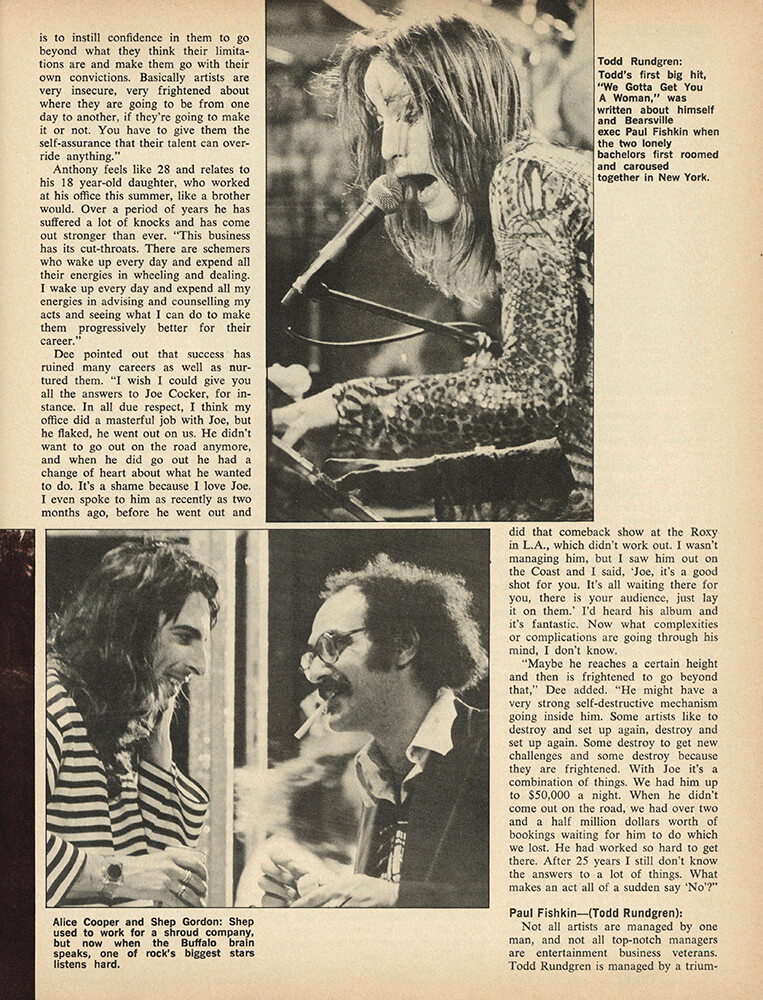

Paul Fishkin — (Todd Rundgren):

Not all artists are managed by one man, and not all top-notch managers are entertainment business veterans. Todd Rundgren is managed by a triumvirate consisting of Paul Fishkin (age 31 and president of Bearsville Records), Albert Grossman (founder of the label), and Susan Lee. Albert makes the deals, Paul runs the record label, and Susan is Todd's personal "babysitter," though they make all their major decisions jointly. Circus Magazine talked to Paul and found his entry into rock management was quite different.

"Todd and I both came from Philadelphia, and in 1966 the same thing was happening there as was happening in San Francisco — a sub-cultural evolution of people for which music was the prime focus. I flashed on this group, Woody's Truck Stop, that Todd was in. I happened to have a little money in the bank from my Bar Mitzvah ($3000), and the group needed backing. I wanted to be involved, so I bought them some equipment they needed, became their manager and got to know Todd. I deal with people's personalities primarily, instead of dealing with them on a business level.

"Historically managers learned their trade as a business, like a kid would take over his father's shoe business. People evolved into the agent-management business pre-1965 in that same kind of fashion — not having anything to do with their particular feeling towards any human qualities in an artist. I started in exactly the opposite way. I was involved with the artists as friends. We were all part of this little group of people who were living together. I learned management, not from any book and not technically, but simply by being their friend. I learned how to deal with them in relation to what we had to get done. Because I wasn't a musician, I had more of a sense of the practical aspects of the group, making their fantasies into realities, which is exactly what I do today."

During the last eight years, Todd went on to form other groups (Nazz, Runt, Utopia) and produce and make records. Paul became officially reinvolved with Todd on a business basis when the wizard's first solo LP, Runt, came out. "His first single was 'We Gotta Get You A Woman,' and because the record company he was involved with was not functioning correctly, I started promoting the record on my own and it became a hit. One thing led to another and here I am. It's important to understand that Bearsville doesn't separate the management from the agent from the record company as has historically been done in the past. Here it's a natural, unilateral progression of friends who are all in business with the same goal. All the conflict and competitiveness of the different titles that only cause grief for the artist have been removed. Ultimately, it makes it as good as it can be for Todd. This kind of arrangement is happening all over the business right now."

Marty Thau — (New York Dolls):

Two years ago, Mr. and Mrs. Marty Thau wandered into the Mercer Arts Center and heard the New York Dolls. Marty chatted with lead singer David Johanson after the set. Since that night, he and Steve Leber have guided the punk team's career through two albums, and gone from earning five dollars each on concert dates to hauling in up to $13,000 a night, which is good money for what Thau calls "the strongest middle act in the business."

Marty was involved with the birth of Buddah Records and was partly responsible for bringing out such hits as "96 Tears," "Green Tambourine," "It's Your Thing," "Yummy, Yummy, Yummy," and "Oh Happy Day" as well as songstress Melanie. The Dolls are his first attempt at management, but he believes his inexperience may in some ways be a plus.

"I didn't know that you didn't have a rock concert at The Waldorf or that you didn't go to England without a record contract, all things that did actually work after everyone had said 'No'." Marty isn't superflash show business but rather low-key, serious, married and into being a parent to his kids. "I had my days of drinking, drugging, and whoring," the 35-year old wistfully mused recently. The Dolls are now his only business and although he is impatient for the rest of the world to catch up with The Dolls' mentality, he predicts they will make him a millionaire within four years. He is not just in the business to rip it off for the buck, though, Marty wants to be part of history. He thinks of himself as an artist, not unlike Fellini — a mentor to the masses. Thau totally believes in the Dolls and constantly works with them, bouncing ideas off them, exerting a moral influence when he feels he should, and giving them an overview. He and Steve Leber get twenty percent of the Dolls' dough and, until they hit it big, give them weekly salaries, pay their rent, buy them clothes, and establish credit for them around the world.

"It is a serious trip for me, not a game," Marty affirmed with an easy manner. "I'm the Phil Spector of the rock world." He and his wife travel with the Dolls to all important gigs. They haven't given him any flamboyant presents yet, but when they make it he wants a helicopter. The Dolls visit him at his country mansion and he would like to have David as a son-in-law but, he's stated, "David is going to marry Caroline Kennedy."

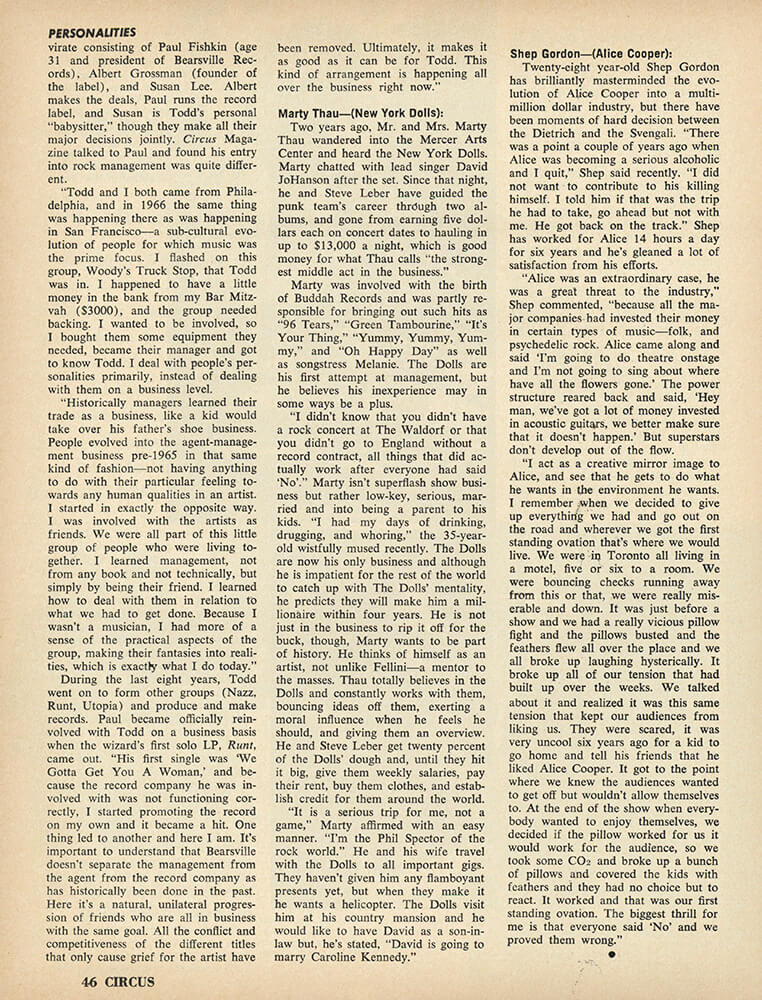

Shep Gordon — (Alice Cooper):

Twenty-eight year-old Shep Gordon has brilliantly masterminded the evolution of Alice Cooper into a multi million dollar industry, but there have been moments of hard decision between the Dietrich and the Svengali. "There was a point a couple of years ago when Alice was becoming a serious alcoholic and I quit," Shep said recently. "I did not want to contribute to his killing himself. I told him if that was the trip he had to take, go ahead but not with me. He got back on the track." Shep has worked for Alice 14 hours a day for six years and he's gleaned a lot of satisfaction from his efforts.

"Alice was an extraordinary case, he was a great threat to the industry," Shep commented, "because all the major companies — had invested their money in certain types of music — folk, and psychedelic rock. Alice came along and said 'I'm going to do theatre onstage and I'm not going to sing about where have all the flowers gone.' The power structure reared back and said, 'Hey man, we've got a lot of money invested in acoustic guitars, we better make sure that it doesn't happen.' But superstars don't develop out of the flow.

"I act as a creative mirror image to Alice, and see that he gets to do what he wants in the environment he wants. I remember when we decided to give up everything we had and go out on the road and wherever we got the first standing ovation that's where we would live. We were in Toronto all living in a motel, five or six to a room. We were bouncing checks running away from this or that, we were really miserable and down. It was just before a show and we had a really vicious pillow fight and the pillows busted and the feathers flew all over the place and we all broke up laughing hysterically. It broke up all of our tension that had built up over the weeks. We talked about it and realized it was this same tension that kept our audiences from liking us. They were scared, it was very uncool six years ago for a kid to go home and tell his friends that he liked Alice Cooper. It got to the point where we knew the audiences wanted to get off but wouldn't allow themselves to. At the end of the show when everybody wanted to enjoy themselves, we decided if the pillow worked for us it would work for the audience, so we took some CO2 and broke up a bunch of pillows and covered the kids with feathers and they had no choice but to react. It worked and that was our first standing ovation. The biggest thrill for me is that everyone said 'No' and we proved them wrong."