Article Database

Late Late Rock: TV's New Sound and Fury

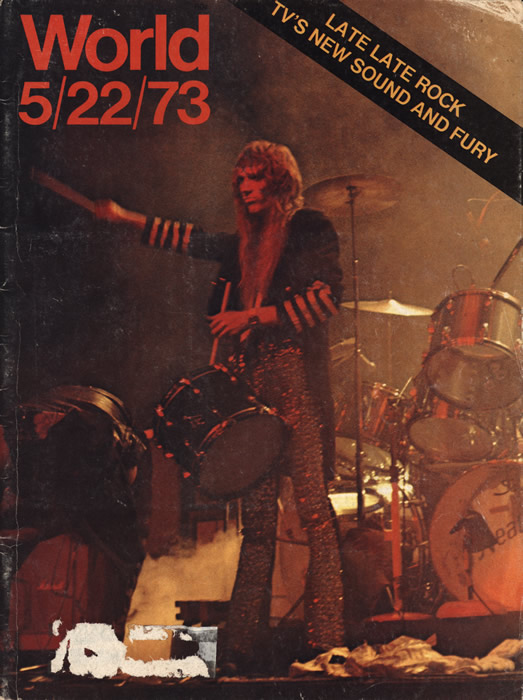

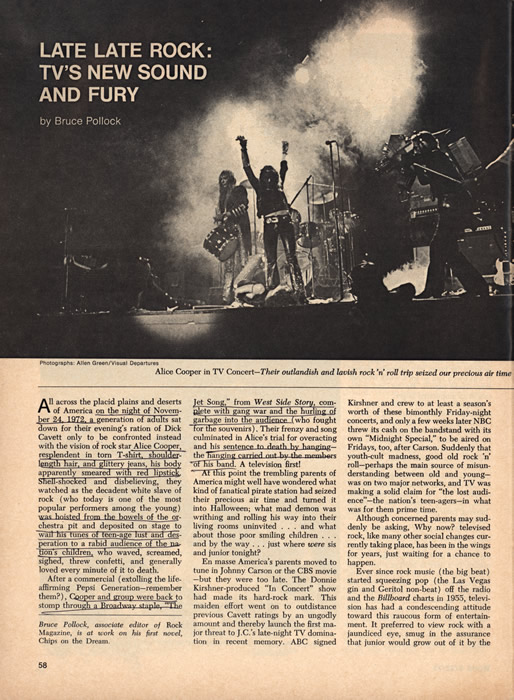

All across the placid plains and deserts of America on the night of November 24, 1972, a generation of adults sat down for their evening's ration of Dick Cavett only to be confronted instead with the vision of rock star Alice Cooper, resplendent in torn T-shirt, shoulder-length hair, and glittery jeans, his body apparently smeared with red lipstick. Shell-shocked and disbelieving, they watched as the decadent white slave of rock (who today is one of the most popular performers among the young) was hoisted from the bowels of the orchestra pit and deposited on stage to wail his tunes of teen-age lust and desperation to a rabid audience of the nation's children, who waved, screamed, sighed, threw confetti, and generally loved every minute of it to death.

After a commercial (extolling the life-affirming Pepsi Generation - remember them?), Cooper and group were back to stomp through a Broadway stape, "The Jet Song," from West Side Story, complete with gang war and the hurling of garbage into the audience (who fought for the souvenirs). Their fenzy and song culminated in Alice's trial for overacting and his sentence to death by hanging - the hanging carried out by the members of his band. A television first!

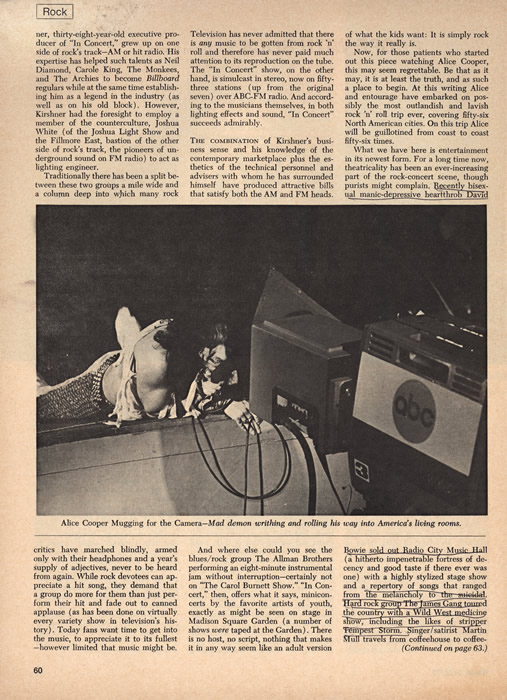

At this point the trembling parents of America might well have wondered what kind of fanatical pirate station had seized their precious air time and turned it into Halloween; what mad demon was writhing and rolling his way into their living rooms uninvited... and what about those poor smiling children... and by the way... just where were sis and junior tonight?

En masse America's parents moved to tune in Johnny Carson or the CBS movie - but they were too late. The Donnie Kirshner-produced "In Concert" show had made its hard- rock mark. This maiden effort went on to outdistance previous Cavett ratings by an ungodly amount and thereby launch the first major threat to J.C. late-night TV domination in recent memory. ABC signed Kirshner and crew to at least a season's worth of these bimonthly friday-night concerts, and only a few weeks later NBC threw its cash on the bandstand with its own "Midnight Special," to be aired on Fridays, too, after Carson. Suddenly that youth-cult madness, good old rock 'n' roll - perhaps the main source of misunderstanding between old and young - was on two major networks, and TV was making a solid claim for "the lost audience" - the nation's teen-agers - in what was for them prime time.

Although concerned parents may suddenly be asking, Why now? televised rock, like many other social changes currently taking place, has been in the wings for years, just waiting for a change to happen.

Ever since rock music (the big beat) started squeezing pop (the Las Vegas gin and Geritol non-beat) off the radio and the Billboard charts in 1955, television has had a condescending attitude toward this raucous form of entertainment. It preferred to view rock with a jaundiced eye, smug in the assurance that junior would grow out of it by the time he reached sixteen and into the more adult (and televised) realms of "good music" - typified by Dinah Shore, Perry Como, and "Your Hit Parade."

But it was precisely the adult world's patronizing attitude toward rock that enhanced its appeal to youth who made it their clarion call to rebellion. That their parents considered it sexy and forbidden only made it more attractive - a real alternative (if only in fantasy) to the snug, well-fed life they had been born into in the postwar forties.

And so junior decidedly did not grow out of it; instead, rock grew with him, gradually absorbing all other forms of music around it, putting its funky moniker on such diverse modes of folk/rock, jazz/rock, blues/rock, and even pop/rock. Dinah and Perry were still singing of baboons in June, but their audience was getting older - and there was no new one on its trail.

Always close behind any emerging national trend (by about five years or so), television responded to the needs of the young by grudgingly offering "American Bandstand" (in what was previously Howdy Doody's time slot), Elvis Presley from the waist up on the "Ed Sullivan Show," and three misguided musical bummers named "Hootenanny," "Music Scene," and "Shindig." These shows were pathetic attempts by television to foist on the public its own distorted image of what these strangers, our sons and daughters, were all about. Parents watched these shows for a while and sighed with relief; what their kids really wanted, it seemed, were updated (all the way to 1931) versions of the same variety shows they had watched. Life was simple again. Meanwhile the real gulfs widened; parent vs. youth, TV vs. rock.

Because rather than watching these shows, the young attended folk festivals at Newport and Philadelphia, banned the bomb, were a little uncivil about rights in Mississippi, and played bongos all night in Annette Funicello movies such as Beach Blanket Blecch. Little by little they were beginning to live that adventurous life first inspired by rock 'n' roll. But the next few years would provide a shake-up of manners and morals even King Elvis could not have predicted.

The invasion of the Beatles in the winter of 1964 took the culture by complete suprise - the reverberations of that visit (as seen on Ed Sullivan) to last quite a bit longer than the standard three-minute song. The Beatles personified the subconscious rebellion already taking place. They gave reason for the hopeless middle-class youth to believe there could be an alternative to the dreary degree - marriage - white-shirt- and-tie future their parents had programmed for them. In manner and appearance these newcomers were so far ahead of the rest of the neighbourhood - long-haired, graceful, funny, with no cuffs on their jeans. Junior locked himself in his room and began plotting.

As the Sixties went on, rock performers arose from the repressed legions of the middle class. The quiet kid, the outcast, the ugly, the one who wrote poetry - all were accepted and deified as "freaks," the new hero in the age of rock. Everybody was in a band or at least wrote songs. Before long, these assorted freaks began getting record contracts, and their songs arriving on the charts and earned some of them small fortunes (others, larger fortunes). Born of shared experience, a shared rebellion, the lyrics of these songs spoke to the young as no pop song ever could. Across the country the middle class was dropping out, growing long hair, sampling exotic drugs. Sideburns were known to sprout on even the most confirmed of jocks.

So while Andy and Dino were singing show tunes about romantic love (by and large an unknown concept among those new vagabonds), the kids were responding to "Light My Fire" and "I Get No Satisfaction." And the spectacle of Jack Jones singing their anthem, "Get Together" ("come on, people now, smile on your brother, every body get together, try to love one another right now..."), was ludicrous. His experience of that song could not have been in any way similar to the experience of the person who wrote it. Had Jack traveled the same road through acid to nirvana? Impossible. It was only on television that a lie like that could be believed. Which is why most rock people basically distrusted the monster medium, with its image of the establishment and selling out, almost as much as television and the adult world in general misunderstood and despised their music. Clearly there was a communication gap.

Then, slowly, things began to loosen up. The waves made at Chicago and Woodstock reached even the isolated shores of TV alnd. In such seemingly disconnected ventures as "All in the Family," "The Dick Cavett Show," "Maude," and public television, the way was paved for rock to be portrayed realistically on the screen. Archie's bigotry, Maude's abortion, Cavett's deferential treatmeant of the Ono-Lennons (to the point of abject awe), the public televion's insightful portraits of such underground rock people as Roy Buchanan, Leon Russel, and The Grateful Dead gave indications that TV as finally lifting its corporate head out of the sand and hearing in the air the voices of the young.

The time seemed right for network TV to take the plunge again. After all, wasn't rock big business by now? Didn't the little darlings of "Bandstand" land constitute a market ample enought to interest even the most conservative of sponsors? The tentative answer was, well, maybe. But how were they to avoid another disaster? How would they suddenly become authentic enough to suit the purist youth who called this music their own?

The answer was found in teamwork: a combination of media and counterculture talent. For instance, Donnie Kirshner, thirty-eight-year-old executive producer of "In Concert," grew up on one side of rock's track - AM or hit radio. His expertise has helped such talents as Neil Diamond, Carole King, The Monkees, and The Archies to become Billboard regulars while at the same time establishing him as a legend in the industry (as well as on his old block). However, Kirshner had the foresight to employ a member of counterculture, Joshua White (of the Joshua Light Show and the Fillmore East, bastion of the other side of rock's track, the pioneers of underground sound on FM radio) to act as lighting engineer.

Traditionally there has been a split between these two groups a mile wide and a column deep into which many rock critics have marched blindly, armed only with their headphones and a year's supply of adjectives, never to be heard from again. While rock devotees can appreciate a hit song, they demand that a group do more for then than just perform their hit and fade to canned applause (as has been done on virtually every variety show in television's history). Today fans want time to get into the music, to appreciate it to its fullest - however limited that music might be. Television has never admitted that there is any music to be gotten form rock 'n' roll and therefore has never paid much attention to its reproduction on the tube. The "In Concert" show, on the other hand, is simulcast in stereo, now on fifty-three stations (up from the original seven) over ABC-FM radio. And according to the musicians themselves, in both lighting effects and sound, "In Concert" succeeds admirably.

The combination of Kirshner's business sense and his knowledge of the contemporary marketplace plus the esthetics of the technical personnnel and advisers with whom he has surrounded himself have produced attractive bills that satisfy both the AM and FM heads.

And where else could you see the blues/rock group The Allman Brothers performing an eight-minute instrumental jam without interruption - certainly not on "The Carol Burnett Show." "In Concert," then, offers what it says, miniconcerts by the favorite artists of youth, exactly as might be seen on stage in Madison Square Garden (a number of shows were taped at the Garden). There is no host, no script, nothing that makes it in any way seem like an adult version of what the kids want: It is simply rock the way it really is.

Now, for those parents who start out this piece watching Alice Cooper, this may seem regrettable. Be that as it may, it is at least the truth, and as such a place to begin. At this writing Alice and entourage have embarked on possibly the most outlandish and lavish rock 'n' roll trip every, covering fifty-six North America cities. On this trip Alice will be guillotined from coast to coast fifty-six times.

What we have here is entertainment in its newest form. For a long time now, theatrically has been an ever-increasing part of the rock-concert scene, though purists might complain. Recently bisexual manic-depressive heartthrob David Bowie sold out Radio City Hall (a hitherto impenetrable fortress of decency and good taste if there ever was one) with a highly stylized stage show and a repertory of songs that ranged form the melancholy to the suicidal. Hard rock group The James Gang toured the country with a Wild West medicine show, including the likes of stripper Tempest Storm. Singer/satirist Martin Mull travels from coffeehouse to coffeehouse with his living- room furniture. The Pink Floyd performs its hypnotic music from within an environment resembling the final moments of 2001, complete with exploding stars and mist. The evil image of Mick Jagger seen during his recent tour quickly became the new look among the after-school set. Rock is the new vaudeville, and when Dino bows off the tube, there will be a rock act to replace him. TV can only help speed the process.

This is not to say that the empire is in any immediate danger of falling. "In Concert" will have to widen its scope to represent an even truer picture of the rock scene at large. NBC's "Midnight Special" is nothing more than a warmed-over Las Vegas imitation of "Your Hit Parade." Performers do their hit and fade off with smiles and bows. This images will not attract the die-hard fan but might make a dent among those who would otherwise watch the late movie or read a true-confessions magazine. (You didn't expect TV to change overnight, did you?) We still have "American Bandstand" for the kids to dance to, but now there is "Soul Train" for black America, wherein previously unrecognized performers can exhibit their funky wares. And both of the top kid-rock groups, The Osmond Brothers and The Jackson Five, have their own moring cartoon shows!

The film industry has increasingly been having rock musicians write scores for major pictures; often (as in the case of Elton John and the movie Friends) their contribution to the sound track is the only good thing in the film. Even on TV, rock songs are popping up to introduce such popular shows as "The Mary Tyler Moore Show," "Maude," and "NBA Basketball." And many rock tunes originally released commercials, redone slightly, become hit songs (notably, "I'd Like To Teach the World to Sing" - first done for Coca-Cola, then made into a hit by The New Seekers).

On April 14 a show called "Flipside" premiered on 145 stations throughout the country. This show's premise is that the young audience is as interested in in the behind-the-scenes aspects of the music business as they are in the stars. Onthe first show the president of Elektra Records, Jac Holzman, took us into the studio to see folk/rock performers Just Collins and Mickey Newbury in actual recording sessions. In an age when talk in the hallways between classes is no longer of baseball and movie stars but of the rock world - when kids, who don't know when Atlanta came into the league but do know the name of the amplifier used by an obscure guitarist in an obscure group, mingle to swap rock trading cards - the chances of success for a show like "Flipside," if done well, are excellent.

Paul McCartney has had his own special on ABC (April 16), and on NBC Elvis checked in from Hawaii (April 4) with a taped live concert. This summer Grammy winner Helen Reddy is scheduled to replace Flip Wilson. And over on public TV (Considered the most tasteful and superior of all stations in its programming) a thirteen-week series of folk/rock concerts are in the works.

If televised rock can come that far, perhaps we can push it a bit further. Why not bring back the "Amateur Hour," only this time for rock groups? bring back "Songs for Sale" and "Composter of the Week"; we certainly have enough of both in the rock world. If rock on TV can make a dent, it can make a gash - entertainment for the highbrow, the lowbrow, and the penciled-brow. As more and more children of the Forties - those long- haired sons and daughters of the peace movement, the summer of love and the Woodstock mudslide, who grew up to Elvis and Ricky Nelson, who matured to teh Baetles and The Stones - begin to infiltrate adule society, either by necessity or design, and to reach positions of power and prestige, then change will occur. And change is on the way. As ad execs they wil want to sponsor realistic comedies and dramas and rock shows such as "Flipside" and "In Concert." As audiences their tastes will have to be satified.

Thanks to the courageous ground-breaking efforts of their big borther and sisters, the children of the Fifties and Sixties have simply never known a time when rock music wasn't the only music of any value. The revolution may not have eben won, but many changes did occur, and for the time being the children of the Seventies are working with them. Rock is their music, even more than anyone else's, and they are expanding it to the limits and beyond. Television, to keep pace, had better keep its camera eyes open.