Article Database

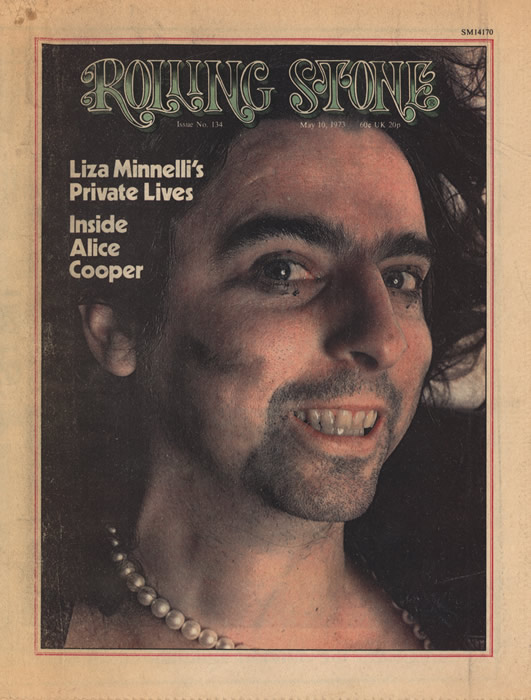

Inside Alice

"Alice is such an American name. I love the idea that when we first started, people used to think Alice Cooper was a blonde folk singer.

"The name started simply as a spit in the face of society. We decided on it in about 1968: With a name like Alice Cooper we could make 'em suffer.

"I was certainly not making a sexual statement. We never wore girl's make-up. We used mime make-up. I was always more of a monster than a drag queen. I don't like to do it - I'm not into it. I'm into the glamour rock thing, 'cause that's important.

"I love the idea of confusion. I think a valid point or art is chaos. I love the idea of not really knowing what the audience is thinking, and not really caring what they're thinking.

"For instance, if you pull a snake out, it's going to mean 15 different thing to 15 different people. If I pulled a snake out right now, this person would be scared, this person would think it was funny, and this person might be sexually aroused. A snake is that kind of thing.

"That's how Salvador Dali works. He pulls out a brain - that's dripping. When people see it they're all going to get different ideas about it, but all it is an image. My whole idea is not to preach anything. Just give them images to fantasize with. You can use a pound of hamburger and somebody might be sexually aroused."

You use a pound of hamburger on stage?

"No, but that's not a bad idea. You could smear a pound of hamburger all over a picture of Marilyn Monroe. That would really create some sort of confusion."

You'd have to use a more contemporary person since much of your young audience wouldn't recognize her.

"Sure! You could use Lee Harvey Oswald. Hamburger on Lee Harvey Oswald. I'm really just into seeing what reactions that gets."

Like reactions to your own death?

"It was an obvious and necessary thing that I had to do. That's a real guillotine up there. The blade weighs 40 pounds and it's razor sharp. There's just one safety catch on it. . . . You see, all death is sexual. And when Alice does something onstage, he has to be punished for it. He always gets killed in the end. Just like in the movies.

"Although we did a month of dress rehearsals before we went out on this tour, we really don't write the show; a few of us just put it together. What I do is that I am the director, and I sit down with Shep, my manager, and sometimes Joe Gannon - he's about 40 - and say, OK, we're gonna do 'Dead Babies' and what can I do? So of course you chop up a baby, right? And you stuff it between a mannequin's legs, right?

"See, when you have a thing like that, you can't just sing it, you've gotta go up there and act it out. So I use these mannequins onstage, and I have sex with the mannequins in 'I Love The Dead.' "

And it's mainly kids that get off on this?

"Younger kids are more susceptible to sexual fantasies. When I was 16, I was always think about what I then thought were extremely dirty sexual fantasies. There's nothing really dirty. Alice provides a sexual outlet. We're not trying to preach anything, we're there to have fun.

"And I love young girls. As an audience they're really cool. When they're coming to a show, they're not going there to judge it. If it's fun, it's fun and if it's not then they leave. We go all out, to make sure our shows are fun.

"I could think of other things to do, but I'm very happy with what I'm doing right now. It's the best way it get my violent things out and to get my sexual aggressions out."

"See, Alice onstage doesn't think. Alice is an animal. Whatever happens, happens. I don't even have a chance to control him that much onstage. And the audience has so much fun observing him, like the sacrificial calf up there. He's exposing everything in my personality and they love to watch it. It's voyeurism; and it's sadism. It really is. I kiss a 14-year-old every night onstage."

You are De Sade, aren't you?

" 'Dead Babies' was a De Sade idea - not his idea, but I had just seen the musical version of De Sade in Europe. I felt it was important to do it in America, to act out violent sex in front of American youth."

Why? Why you?

"Because they need it. Because if they believe what their parents are saying, they're going to go crazy. And they're all going to commit suicide. But if they listen to me, and just work out their sexual fantasies, they're going to be a lot healthier mentally.

"As long as sex doesn't hurt anybody, what's wrong with it? There's nothing wrong with any perversion, as long as it doesn't hurt anybody, physically hurt anybody, although on some levels some people like to be hurt sexually.

"You could consider Alice Cooper the De Sade of rock, because that was De Sade's purpose in life. He opened up imaginations, sexual imaginations."

But he had a private life full of it.

"Well, so do I. But that's - like you said - a private life."

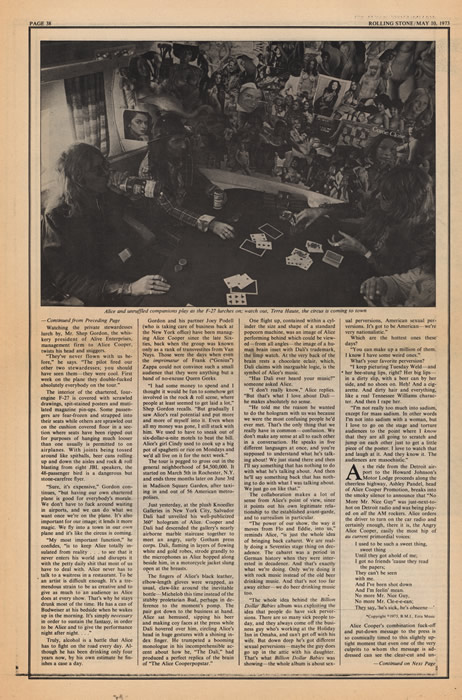

Alice Cooper shining F-27 with the black dollar sign emblazoned on its tail is zigzagging without apparent purpose from Pittsburgh to Detroit. The plane was shaking so violently that the stewardess, as she comes staggering out of the pilot's cabin, falls into the lap of a recently hired guitarist who has joined the Alice Cooper Band for the length of this tour. He is clutching the shifting, jello-bag chair he is sprawled in and stares in fear out the porthole.

Aynsley Dunbar, veteran British drummer who is accompanying Alice's warm-up act, Flo and Eddie, abruptly ceases gnawing the glitter off his fingernail and screams: "Holy shit! The pilot is going to fuckin' kill us!"

One of the Flo and Eddie roadies leans over to Dunbar. "Don't worry, Aynsley - it's a short flight to Detroit, just a hop, skip and a plunge."

Aynsley whimpers. His heads sinks into his studded leather jacket.

Watching the private stewardesses lurch by, Mr. Shep Gordon, the whiskery president of Alive Enterprises, management firm to Alice Cooper, twists his head and sniggers.

"They've never flown with us before," he says. "The pilot fired our other two stewardesses, you should have seen them - they were cool. First week on the plane they double-fucked absolutely everybody on the tour."

The interior of the chartered, four-engine F-27 is covered with scrawled drawings, spit-stained posters and mutilated magazine pin-ups. Some passengers are fear-frozen and strapped into their seats while others are sprawled out on the cushion covered floor in the section where seats have been ripped out for purposes of hanging much looser than one usually is permitted to on airplanes. With joints being tossed around like spitballs, beer cans rolling up and down the aisles and rock & roll blasting from eight JBL speakers, the 48-passenger bird is a dangerous but stone-carefree flyer.

"Sure, it's expensive," Gordon continues, "but having our own chartered plane is good for everybody's morale. We don't have to fuck around waiting in airports, and we can do what we want once we're on the plane. It's also important for our image; it lends it more magic. We fly into a town in our own plane and it's like the circus is coming.

"My most important function," he confides, "is to keep Alice totally insulated from reality . . . to see that it never enters his world and disrupts it with the pretty daily shit that most of us have to deal with. Alice never has to talk to a waitress in a restaurant. To be an artist is difficult enough. It's a tremendous strain to be as creative and to give as much to an audience as Alice does at every show. That's why he stays drunk most of the time. He has a can of Budweiser at his bedside when he wakes up in the morning. It's simply necessary in order to sustain the fantasy, in order to be Alice and to give the performances night after night. . . ."

Truly, alcohol is a battle that Alice had to fight on the road every day. Although he has been drinking only four years now, by his own estimates he finishes a case a day.

Gordon and his partner Joey Podell (who is taking care of business back at the New York office) have been managing Alice Cooper since the late Sixties, back when the group was known only as a rank of transvestites from Van Nuys. Those were the days when even the imprimatur of Frank ("Genius") Zappa could not convince such a small audience that they were anything but a band of no-excuse Queen Geeks.

"I had some money to spend and I thought it would be fun to somehow get involved in the rock & roll scene, where people at least seemed to get laid a lot," Shep Gordon recalls. "But gradually I saw Alice's real potential and out more and more of myself into it. Even when all my money was gone, I still stuck with him. We use to sneak out of six-dollar-a-night motels to beat the bill. Alice's girl Cindy used to cook up a big pot of spaghetti or rice on Mondays and we'd all live on it for the next week."

The tour is pegged to gross out in the general neighborhood of $4,500,000. It started on March 5th in Rochester, N.Y. and ends three months later on June 3rd in Madison Square Garden, after taxing in and out of 56 American metropolises.

Just yesterday, at the plush Knoedler Galleries in New York City, Salvador Dali had unveiled his well-publicized 360 degrees hologram of Alice Cooper and Dali had descended the gallery's nearly airborne marble staircase together to meet an angry, surly Gotham press corps. Dali, flaming in layers of flowing white and gold robes, strode grandly to the microphones as Alice bopped along besides him, in a motorcycle jacket slung at the breasts.

The fingers of Alice's black leather, elbow-lengthed gloves are wrapped, as usual, claw-like around the inevitable bottle - Michelob this time instead of the stubby proletarian Bud, perhaps in deference to the moment's pomp. The pair got down to business at hand. Alice sat bemused, sipping his beer and making coy faces at the press while Dali hovered over him, circling Alice's head in huge gestures with a shining index finger. He trumpeted a booming monologue in his incomprehensible accent about how he, "The Dali," had produced a perfect replica of the brain of "The Alice Cooperpopstar."

One flight up, contained within a cylinder the size and shape of a standard popcorn machine, was an image of Alice performing behind which could be viewed - from all angles - the image of a human brain inset with Dali's trademark, the limp watch. At the very back of the brain rests a chocolate eclair, which, Dali claims with inarguable logic, is the symbol of Alice's music.

"Has Dali ever heard your music?" someone asked Alice.

"I don't really know," Alice replies. "But that's what I love about Dali - he makes absolutely no sense.

"He told me the reason he wanted to do the hologram with us was because we were the most confusing people he'd ever met. That's the only thing we have in common - confusion. We don't make any sense at all to each other in a conversation. He speaks in five different languages at once, and you're supposed to understand what he's talking about! We just sat there and then I'll say something has nothing to do with what he's talking about. And then he'll say something back that has nothing to do with what I was talking about. We just go on like that."

The collaboration makes a lot of sense from Alice's point of view, since it points out his own legitimate relationship to the established avant-garde, and to the surrealism in particular.

"The power of our show, the way it moves from Flo and Eddie, into us," reminds Alice, "is just the whole idea of bringing back cabaret. We are really doing a Seventies stage thing on decadence. The cabaret was a period in German history when they were interested in decadence. That's exactly what we're doing. Only we're doing it with rock music instead of old beer drinking music. And that's not too far away either - we do beer drinking music too.

"The whole idea behind the Billion Dollar Babies album was exploiting the idea that people do have sick perversions. There are so many sick people today, and they always come off the business guy who's working at the Holiday Inn in Omaha, and can't get off with his wife. But down deep he's got different sexual perversions - maybe the guy does go up in the attic with his daughter. That's what Billion Dollar Babies was showing - the whole album is about sexual perversions, American perversions. It's got to be American - we're very nationalistic."

Which are the hottest ones these days?

"You can make up a million of them. I know I have some weird ones."

What's your favourite perversion?

"I keep picturing Tuesday Weld - and her bee-stung lips, right? Her big lips - in a dirty slip, with a beer can by her side, and no shoes on. Heh! And a cigarette. And dirty hair and everything, like a real Tennessee Williams character. And then I rape her.

"I'm not really too much into sadism, except for mass sadism. In other words I'm not into sadism with a woman, but I love to go on stage and torture audiences to a point where I know that they are all going to scratch and jump on each other just to get a little piece of the poster. I love to watch that and laugh at it. And they know it. The audience are masochistic."

As the ride from Detroit airport to the Howard Johnson's Motor Lodge proceeds along the cheerless highway, Ashley Pandel, head of Alice Cooper Promotions, breaks into the smoky silence to announce that "No More Mr. Nice Guy" was just-next-to-hot on Detroit radio and was being played on all the AM rockers. Alice orders the driver to turn on the car radio and certainly enough, there it is, the Angry Alice Cooper, easily the most hip of au current primordial voices:

I used to be such a sweet thing, sweet thing

Until they got a hold of me;

I've got no friends 'cause they read the papers;

They can't be seen with me.

And I've been shot down

And I'm feelin' mean.

No more Mr. Nice Guy

No more Mr. Cle-e-e-ean;

They say, 'he's sick, he's obscene-'

Alice Cooper's combination fuck-off and put-down message to the press is so cosmically timed to this slightly uptight moment that even one of the very culprits to whom the message is addressed can see the clean-cut and unabashed irony of it all as he sits squeezed next to Alice. And on top of that insouciant insult, Alice is actually singing along, just kind of carelessly grooving with himself, but maybe just a hair too carelessly . . .

The song must have provided Alice with a nice sense of nobility; all at once he assumes the benevolence of a man who knows that he has made his point and made it well. His hand suddenly darts into his carpetbag to tap the last can of Budweiser. Snapping off the poptop and assaying a professional swig, Alice passes it to his early morning guest.

"I can empathize with anyone who drinks beer in the morning," says Alice in simple tones, edging toward the graciousness which befits a billion-dollar baby. Many other worlds are befitting him these past three years as well, he feels.

"I just bought a house right next door to Barry Goldwater. It was a tax shelter thing where I had to get rid of some money, and bought a house. Heh! In about five years I'm going to move there. I'm renting it right now to the president of a chemical corporation, and it's a good investment, anyway. He probably knows by now what I'm going to do is have a mystery neighbor party, wear a bag over my head, and invite all the neighbors. A lot of the Phoenix bigwigs live right in this area, Paradise Valley. When they're all there I'm gonna take the bag off. The cool thing is my house is bigger than his! And I have more money than him. But Barry Goldwater's really a pretty good guy."

Phoenix is Alice's hometown, where he claims he had "a real cool childhood." His return there will no doubt be prodigious, but it will also be only private; the city will not allow him to play any of its concert halls.

"I'm not trying to kill myself," Alice continues, "that's silly. I have a lust for life; I wouldn't be doing this if I didn't really like seeing new places and doing new things. I love the idea of life, yet I have this other self and he goes up there and makes fun of death.

"Offstage, I'm Ozzie Nelson. I'm gentle. I walk around eating cookies and milk - well, not milk, cookies and beer. I work in opposites. Offstage I'm pretty . . . nonviolent. I'm stable. I have a girlfriend, the same girl for five years now, Cindy. She isn't on the tour because she hates us. She hates our music and she hates our image. She's a gorgeous, beautiful girl - one of the most sought-after ladies in New York. I really like the fact that she hates us.

"I work in opposites. If I'm exposing myself that much onstage - not physically, but mentally exposing myself all my problems on stage - I would rather not let a lot of people know what I really do."

Press conferences are held in every city. They are, by and large, boisterous and boozy affairs in which the local reporters only rise to the oft-heard straight lines.

Midway in each local Meet The Press, just when it begin to appear that Alice might imminently keel with teenage boredom from keeping the Bulletin, Dispatch and News-Herald gnomes and cretins amused as the questions become fewer and duller . . . Midway through each press conference, Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan, who are Flo and Eddie, suddenly heel into the conference room, rendering an off-key "Stout Hearted Men." They sit down with Alice to face a nation's free press like The Three Stooges Revisited.

Volman, who once played with the Turtles, spreads and immense belly in front of him like a biologically self-sustaining organism. Furthermore, peppery shocks of frizzed-out curls lift straight out and up from both sides of his head. Volman revels in the display of his undeniable sheer grossness. But, on the other hand, he usually wears a pith helmet on top of which perches his pet flamingo, Hawk. "Talk about flash!" wrote Bill Krayon in that afternoon's late editions.

Alice still hasn't publicly revealed his real name.

"I told the press today," he reports later, "that I was Jimmy Piersol's illegitimate son. I think that's a great idea. For some reason that really fits my sense of humour. Did you see The Jimmy Piersol Story? He was totally nuts! He was the Alice Cooper of baseball. He was always hitting people with bats. I decided today that I was going to be his illegitimate son. Now that the Eddie Haskell thing is finally dead, people are going to think I'm young Piersol.

"Oh, O love to lie. That's one of my favourite things in the world, coming up to somebody, especially press people, and telling them some enormous lie that couldn't possibly be true. You can throw in anything you want."

Alice chooses to have Flo and Eddie join him at the daily press preliminaries rather than the members of his own band. All four of his musicians appear, once offstage, to be manic-depressives in varying clinical degrees. They tend to hang together, wary of outsiders. This is due in some measure to their lack of importance in the show as individuals, but primarily to the years of constantly beating off the attacks Alice provokes in factory town bars, California truckstops and other like-minded hangouts. Alice is quite frank about it.

"Every once in a while Alice will pop up when I'm not expecting it," Alice explains. "Especially though in bars when I'm real wiped out. Last night, I got carried out of another one. I was saying some awfully bad things about cripples and I was telling thalidomide jokes. I was just awful. And I was telling Kennedy jokes, too, like how they had to recall all the Kennedy half dollars 'cause they forgot the hole. But then I blurted out about the thalidomide child that could count to 11 on one hand. Helen Keller jokes - I mean those are sick! For some reason, when it's one of those things that you're not supposed to say, it's always a lot funnier. I love sick jokes. We had a Bangla Desh one: 'What the last thing that they need in Bangla Desh?' 'After dinner mints.' "

Backstage in Detroit, Alice quietly introduces his mother. "Have you met my mom? Isn't she just like Tammy Wynette?"

Now, what can this genuinely pleasant middle-aged woman, wife to an ordained minister, think of her son? In the first place, why does he call himself Alice? But what must "Mrs. Cooper" ponder on while she watches her son greet the demi-monde's atavistic backstage set in a moth-eaten dressing room which, like dressing rooms or most civic auditoriums, favors the brightly-lit public lavatory ambience. What or who does "Mrs. Cooper" possibly hold responsible for the ugly-duckling son who chose the life of a truly weirded-out, somewhat magical - yes magical - swan? Not to mention, for a moment, his stage costume, the white leotard, torn in spots as if gnawed by rats, conjoined to one of Alice's personally designed pairs of aqua-shaded leopard-skin thigh boots with six-inch platform heels.

It's what you do for a living these days, she easily teases to neighbors, after Alice's occasional family visits. There's a Rolls Royce, a gift from Alice that "Reverend Cooper" drives, which is testament to that. Indeed, America has approved of Alice with its most glorious honors, and that justifies the "Coopers" private hopes that their son was only calculating it for these last seven years, and didn't really believe in it as a way of life. It's only that first album cover, Pretties For You, which still makes her throat tighten.

"I've been throwing up every single morning of this tour," Alice is telling her, "but it's not from drinking. I've got a real bad head cold and it's in my chest now. Every morning, I wake up and watch all my quiz shows and drink two or three warm beers, 'cause it's good for your stomach in the mornings. Then I get phlegm in my throat and gag. I just throw up water, but then I feel great! It makes you feel so alive. The doctor came over today, and we all got shots, B-12 and things like that. He examined me and said I'm the healthiest one in the group. As bad as I look."

"Alice has always been unusual," she says. She pulls out the wrinkles of her pants-suit, nods her lightly lacquered beehive and in a brave, matter-of-fact tone concludes: "Alice has always done exactly what he's wanted to. He's always been Alice to us."

Hello Hurray,

Let the show begin

Ready as the audience

That's coming into a dream

Loving every second, every moment, every scream.

Among Alice's own lyrics, these make the statement that the only spectacle that can amuse or amaze the jaded young patrons of this decadent new concert fantasy is the potential of live visions of torture, mutilation and necrophilia. For starters.

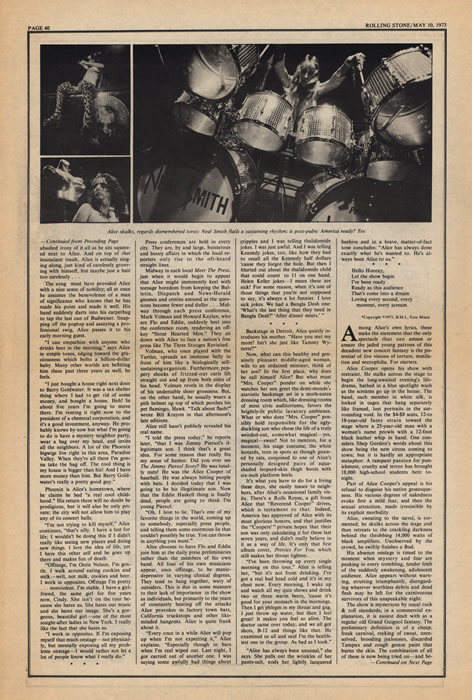

Alice Cooper opens his show with restraint. He stalks across the stage to begin a long-waiting evening's life-drama, bathed in blue spotlight wash as the screams go up in the house. The band, each member in white silk, is locked in cages that hang seperately like framed, lost portraits in the surrounding void. In the $4-$8 seats, 12-to-18-year-old faces strain toward the stage where a 25-year-old man with a woman's name prowls with a 12-foot black leather whip in hand. One considers Shep Gordon's words about this show being the new circus coming to town; but it hardly an appropriate metaphor: A rampant passion for punishment, cruelty and terror has brought 18,000 high-school students here tonight.

Part of Alice Cooper's appeal is his refusal to disguise his native grotesqueness. His various degrees of nakedness evoke first a mild fear, and the sexual attraction, made irresistible but its explicit morbidity.

Alice, sweating to the navel, is tormented; he skulks across the stage and then retreats to the crackling darkness behind the throbbing 14,000 watts of black amplifiers. Unobserved by the crowd, he swiftly finishes a Bud.

His absence onstage is timed to the moment when mystery and fear are peaking in every trembling, tender limb of suddenly awakening, adolescent audience. Alice appears without warning, strutting triumphantly, disregarding whatever worthless debris and dead flesh may be left for the carnivorous survivor of this unspeakable night.

The show is mysterious by usual rock & roll standards; in a commercial explanation, it is easiest dealt with as a regular old Grand Guignol fantasy. The preliminary definition is of a cheap, freak carnival, reeking of sweat, unresolved, brooding jealousies, discarded Tampax and rough grease paint that burns the skin. The combination of all these is now being tried on - and being devoured with equivalent excitement and hunger by - the presumably average post-pubic American adolescents.

In strict terms of concert showmanship, Alice Cooper's is perhaps the most completely realized stage performance of its genre ever presented. The musicians are metamorphosed into minor acolytes. With angry, contemptuous concealment, they move within the mazes on the several levels of the stage. Alice welcomes us to a dream without description, only experience. In the second part of the show, Alice quickly assumes and even more sinister character, that of the violent rapist in Raped And Freezin'. He impales a silver bust (perhaps one of the experimental real-life department store dummies) on a microphone stand, and bashes it with his cane in a screaming rage. And the inchoate, steaming, senseless resentment builds.

There is a scene that moves Alice Cooper into the front rank of rock vocalists. Here; finally his voice masters a weird and fantastic range, loosed from the depth of his fury. It happens to be the really sinister piece, the one whose symbology is clearly the most frightening.

Before the song begins, the roadies, moving quickly as if grave robbers just before dawn, empty onto the stage a rough hewn wheelbarrow filled with dismembered department store dummies, unattached hands, amputated torsos, wooden legs and limbs ripped from sockets, prosthetic appliances of the most tragic kinds. Then twisted babydolls with smashed heads are thrown onto this big ugly Dachau death pile. Or maybe one of those trenches at My Lai. Among the plagued, dismembered landscapes Alice struts, kicking baby heads into the crowd like Quasimodo gone berserk.

Next, brandishing a sword, he impales limbs, smashes bony heads and tender craniums in a frenzied, mad dog dance. He sings a syncopated tango-like lyric that rises with peristaltic ferocity into howling abandon.

Alice's finale is a simple, elegant anthem of necrophilia, "I Love The Dead," in which the monster Alice is martyred on a guillotine. The band move from their pedestals with the methodical step of the psychopath toward the center stage to brutally twist the wrist-bracelets onto his bleeding arms. Drained and passive, Alice bows his head and with one last helpless jerk into the guillotine slot to receive the punishment for his necrophilia.

Silence. Thunk! Isolated screams are heard.

The hangman pulls the bloody head of Alice Cooper - grisly in its wax-museum reality - out of the basket and twist spastically around the stage with the dripping trophy.

A tape loop of "I Love The Dead" blares maddenly again and again throughout the arena. The drummer and bassist and guitarists - released from their cages - are joined in the darkness by the shadows with whom they parade the headless body in triumph.

Meanwhile, Alice Cooper has crawled unseen behind the dark, towering amplifier banks . . . and is well into a newly cracked can of Bud. He sits, sweating, and listening for the encore, a recording of Kate Smith singing "God Bless America." Like fresh blood rushing into the veins of Frankenstein's monster. And then, reassuringly re-headed, he lifts himself up to join the entire cast onstage - in a salute to the American flag.

Back at his hotel, Alice is shirtless, drained, and curled into a big soft chair in front of a 24-inch Sylvavia color set with a can of the King of Beers in his hand, watching a film starring Omar Sharif. Alice and Omar are good personal friends.

"Omar is a great guy but this film sure is a turkey," Alice remarks. "Watching television is the only thing I love to do. It's probably my favourite hobby. The TV is a vast vault of useless knowledge. And I love it. I just think it's great. I get up in the morning and watch the farm report. It's on at six. I really don't think there's anything wrong with television. A lot of people think that it could be better. Well, everything could be better."

Alice's hulking bodyguard, Mike Ramsey, formerly an MP, a US Army Tournament Boxer and is now a Black Belt in karate, is talking in threatening monotone to some one on the phone who claims to know Alice. "You say you met him when we went to see Fritz The Cat? Do you really expect him to remember this insignificant occasion?"

"Ahhh, nasty," purrs Alice, still staring at the screen.

"No, I'm afraid he doesn't remember you. Goodbye." Ramsey sits back down and ponders his gig with Mr. Cooper. "Well, I'll tell ya, lots of people think it's a glamorous job, working as Alice's bodyguard, or should I say, 'traveling companion' . . ."

"That sounds kinda fruity to me," Alice says.

". . . some people would be damned proud to have an honour and a responsibility like this, but to tell you the truth I don't really give a shit, because as far as I'm concerned the guy's a fuckin' loser!".

Alice slides onto the floor, crackling hysterically.

One of the things that has caught the attention of some journalists who have recently joined the Alice Cooper tour is an enforced air of sophomoric hilarity, laced with endless trivia that seems to never let up. One theory is that since their audience is so young the company must sustain a kind of juvenile attitude in order to survive the teenage masses. The photographer on the tour didn't have a theory; she took to hiding in her room for long stretches when unceasing buffoonery and hyena lunacy would become boring and beyond natural reason. Perhaps it all has to do with what Mr. Cooper's manager spoke of as his most important function: insulating Mr. Cooper from reality so that he may continue his existence in the fantasy world nourishes his art.

"Hey, The Creature From The Black Lagoon is on now," Alice says, flicking the dial to another station. "He is the coolest monster that ever lived. I mean it, I want you to get a look at him when he comes dripping from the Black Lagoon. There's something almost handsome about this monster. . . ."

At Alice's feet is a petite, straight-laced 19-year-old college student named Joyce Ciletti, from Wampum, Pennsylvania. She is doing a psychology thesis on Alice Cooper. During the past two years she has distributed several thousand questionnaires in which people are asked to give their responses to the Alice Cooper phenomenon. At the moment, she is deeply engrossed in studying the form that Alice himself just finished filling out for her.

Also in the room is Detroit's only hip rock critic, who met Alice that morning at the airport. He is not interested in The Creature From The Black Lagoon. From a couch across the room he beckons Joyce Ciletti over. In one hand he is holding a Budweiser and in the other one of those sturdy little battle-gray Sony Cassettecorders.

"It took me a year to write the final questionnaire," she explains. "You have to use certain words so they understand it completely, and it must be set up in a certain fashion, scientifically. I'll be passing them out at probably nine concerts on this tour, about 3000 at each concert.

"The questions are about Alice start out asking what part of the concert did they like the most, dislike the most, and what would they do onstage if they were Alice Cooper. The second part is completely empirical. It's a series of statements they respond to on an agree-disagree scale: 'I feel that Alice Cooper is one of the top groups in the country today.' 'Alice promotes attitudes in favor of homosexuality.' 'After seeing Alice's concert I was more excited than after another concert.' 'Alice's appeal is primarily a sexual one.'

"At this age level, it's a commitment age. The kids are really committed and they're being very underestimated.

"I see Alice as comprising the elements of temper in this era: confusion, sadism, masochism. With Alice, sex and violence is not completely differentiated. It's a combination. For instance, the hanging that he used to have. You'll find that that sexually arouses an audience. They had to quit having hangings in the 1800s because there was extreme debauchery afterwards.

"On death row, for instance, the reporters that are there to see the hanging frequently have an orgasm after the hanging. They stopped having public hangings. But it did sexually arouse the males. We don't know what it does to females. I don't know how it exactly works for Alice, but a lot of girls that I interviewed say, 'Oh, it gave me such supreme satisfaction.' I'm sure they don't know why, but that's the reason. A lot of people have written in and said that's what they liked the most.

"It seems to me that after a concert they are left amazed. They are not left violent, at least from what I see, they aren't. Alice more or less drains them. They're left stunned. Many people say that he's decadent, and that the kids - because they perceive him at a visceral level - aren't getting anything out of it. But some of the comments on the questionnaires are amazing. A typical one would be 'I believe in what Alice is saying in his lyrics, because he's satirizing our society and holding us up to see what he is not the one that's sick but the society's sick.' So on and so forth. Do you mean do I think it causes them to do something violent or sexual?"

"Well, do you think it alters their attitudes?"

"For some people I've talked to, it has a little bit, as far as their attitudes on sex. A lot of them feel different after they see the concert."

"Is it altering their attitudes towards bisexuality and homosexuality?"

"No, no. That is one thing that has not come up in the preliminary results at all. Uh, there's maybe three people, so far, out of all the results, that have said that."

"Then what's it about?"

"Alice is the picture of America 1970s. He's definately Middle-Class American. There's no doubt about it. It's symbolic from his Budweiser through the whole act. And we are definately a very violent society. Just watch TV for a while, or go see The Godfather. Alice understands this, and exactly what it implies, completely."

"What is his insight?"

"He sees that we're all mad, that there is no truly sharp differentiation between abnormality and normality - it's simply a matter of semantics."

After Joyce leaves, in the company of Detroit's only hip rock critic, Alice has a whim to leave a fish head from his dinner plate under Mark Volman's door, and within the instant he is tiptoeing barefoot into the hall. Ten seconds later there is a shattering crash. Mike Ramsey flies from his chair, tearing out the door and down the hall. There, two adolescent girls who've been hanging around the hotel all day, have spotted Mr. C.

"Hey Alice," they call, "can we come and talk to you?" Their mother, who just got off work in the downstairs coffee shop, is with them this time.

"I want your autograph, honey," the older one with the peach breasts demands in the nasal accent of the upper Midwest. And the other one starts whining, too: "Give me your auto . . ."

Alice is drunk. He sees piranha fish all around him, nipping at him, ready to start tearing his arms. Suddenly, he faces them, spinnning towards them on his heels like a gunslinger, and in one flashing instant pulls down his pants and his jockey shorts, swings it right out and wiggles it at them: the flaccid little beetlenut pecker of the superstar.